Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists (33 page)

Read Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists Online

Authors: Scott Atran

“Why bad position?” I asked a Pakistani army man, a dentist who happened to be watching the exchange with delighted curiosity and who spoke fairly good English. He explained that, here, the luckless English soldiers had passed through in 1919 on their way to losing (their third and last war in) Afghanistan.

“Ah, but good position with Nadir Khan in Kabul, tat, tat, tat, tat, tat, good position,” gleefully squealed the man’s equally ancient tea partner, a Wazir tribesman who had joined the father of the last king of Afghanistan in sacking the capital ten years later.

The Afridi lowered his head: “No good position now. No good the fight now. Bad position.”

“Why bad position now?” I asked.

The army dentist queried the two white-bearded gentlemen and came back with a laugh: “They say it’s been so calm since [Kabul was sacked in 1929] that a man has no opportunity to become a man!”

“Bad position,” the Wazir nodded in sad agreement. “Bad position.”

Nothing I had seen or heard while driving across Afghanistan that summer with two Mexican friends in search of a future research site (and a bit of exotic adventure, I grant) hinted that the whole region would soon be ablaze for the next thirty years. There was something I later remembered, though. A former Red Army officer—Tomalchoff, I think his name was—who managed his girlfriend’s bookstore on the Île Saint-Louis in Paris had given me copies of maps he had made of the country, with markings of where gasoline could be found, and told me his old buddies had built a wide cement road across the south of Afghanistan that could support the weight of tanks. “The Russians are coming! The Russians are coming!” he exclaimed, cheerfully citing the title of a film comedy that had been popular about a decade before. But I had made nothing of it then.

First stop out of Iran and into Herat, the ancient city of Aria, whose Persian population Genghis Khan had nearly exterminated in 1221. I came looking for Alexander the Great’s citadel; and I finally found it by its smell, for the palace was now the place where people came to shit. There may have been no value to cultural patrimony, but there was to cultural independence. In Herat, the population first rose up against the Soviets in 1979, killing thirty-five Russian advisers. In return, the Afghan communists, backed by the Red Army, killed nearly twenty-five thousand civilians.

Then we drove north to Mazar-e-Sharif, a city of mostly Tajiks and Uzbeks, where people with both hands missing—someone told me this was because they were repeat thieves who had been punished with amputation, but I can’t confirm that—were rolling chopped raw meat between their toes and placing them on skewers over wood-coals to sell to passersby. In 2001, with help from U.S. air power and special forces, the Northern Alliance took the city, with massive killings of civilians. Because the massacres were perpetrated by allies of the U.S.-backed coalition, no one has (yet) had to pay.

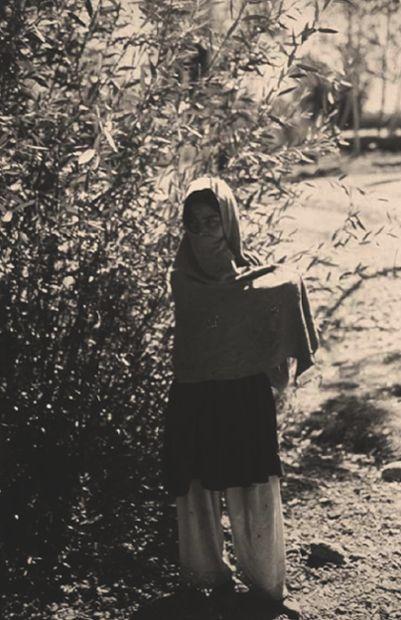

In the center of the country I traveled by horse. Once in a wood I happened on a young woman who had dropped her veil to pull water from a well. I stared at her beauty. She quickly covered her face and scurried away. Suddenly she stopped, turned to me, and took the veil from her face—if ever a look could launch a thousand dreams! I whipped out a camera, but she covered her face as the shutter clicked and ran away. But that moment was burned into my memory for life.

Afghan girl, July 1976.

Near the terraced, turquoise lakes of Bandi Amir, a dull thunder rumbled behind a hill. The most acrobatic horsemen I had ever seen in my life soon shot out from a whirl of dust, playing for the trophy of a headless sheep kept in constant motion. I rode on through this country of the Hazara, descendants of the Mongols, to see the Buddhas of Bamyan, beautiful giant statues carved in the cliffs fifteen hundred years ago. In 2001, the Taliban leader, Mullah Omar, ordered the Buddhas dynamited because they were “idols.” The Sharia scholars of Cairo’s Al Azhar University tried to talk him out of it, but he responded that he would decide what Sharia meant in his country. And why was the outside world so interested in stonework when his people were starving?

In Kabul, it was so hot you could fry an egg on the hood of a car, and I did. Huge Pashtun soldiers in ill-fitting, woolen Red Army surplus fatigues guarded official buildings, and stank mightily but stoically. In the park, even bigger greased-up men were wrestling for a crowd that was cheering, aside from a cluster of silent women shrouded in thick, formless cloth from head to toe except for the latticework at eye level that let them see.

On Chicken Street, cruising in a pink Cadillac with great tailfins, a young man rolled down the window and asked what I was doing. When I told him, he said he wanted to chat about anthropology. We continued in his car, talking about Margaret Mead and Claude Lévi-Strauss, except that every time he saw a pretty Western girl he’d invite her to his village palace and offer to take her up K-2 (the second highest mountain in the world) with or without oxygen. His father was a close cousin of the deposed king, Zahir Shah. We went to his family’s palace (or rather, one of them), where the entire village was at the young man’s call. He had gathered together a motley collection of foreigners—a mad, rustic salon, including one Palestinian man who pressed me all day and much of the night to join him in buying a fleet of refrigerated Mercedes trucks in Germany to ferry lettuce to Saudi Arabia. “Can you imagine,” he said, “a Palestinian and a Jew in such a business together? We could save the Middle East!”

It turned out that the young Afghan lord had been living in exile in Flushing, Queens, New York, but had recently been allowed back by the country’s president, another cousin who had overthrown the monarchy and declared the country a republic. When the communists took power, the first thing they did was to kill the president, Mohammed Daoud Khan, along with a slew of his relatives. I never learned what happened to that extravagant but genial young man, but I suspect he would have been better off staying in Queens.

Through Jalalabad and up toward the Khyber Pass, a curve on a high mountain road suddenly cropped up, our van turned sharply, and the front left wheel went into the void and over what seemed like a thousand-foot drop. The three of us in the van dared not move. As we fruitlessly cursed and debated what to do, a black and blurry line in the distance began to come into focus. It was a very tall Pashtun tribesman, elegant but strongly built, with green eyes full of laughter. He hopped off his horse, roped the van, pulled us to safety, brought us home as guests, and told us what he thought of our lands and his: “America good; Mexico, bandit, very good; Afghanistan top good.”

Into Landi Kotal at the top of the Khyber Pass, I was shooting the breeze with the Afridi tribesman and his Wazir companion (I suspected they had become friends simply because they were old rather than because the traditional enmity between their tribes had lessened), as four young boys somehow managed to unhinge the engine block from the back of our van and were struggling to lift the thing away. The army dentist stopped them with a stern word, shooed them away, and with a smile that showed pleasure both at his thought and his command of English, threw up his hands and said, “Boys will be boys.” Now, after years of almost constant war, I imagine the old Afridi and Wazir would see that such boys had indeed become “men’s men.”

Although reading more than a thousand years of Arab and Muslim history would show little pattern to predict the attacks of 9/11, the present predicament in Afghanistan rhymes as well with the past as the lines of a limerick.

Afghanistan is not like Iraq. And what may work well in Iraq, like propping up governments and surging with troops, may not be so wise for Afghanistan. Iraq is part of Mesopotamia, home to the world’s first centralized government and civilization. Its relatively flat and open geography and great rivers have favored intensive agricultural production, urban development, and easy commerce and communication throughout history. In Mesopotamian Iraq, central governments supported by large standing armies have brought order and stability. Not so in Afghanistan or the border regions of Pakistan, which are also not like Vietnam in the 1960s and 1970s, where a strong state backed communist insurgents. They must be dealt with on their own terms.

The harsh, mountainous, landlocked country of Afghanistan is midway along the ancient Silk Road connecting China and India to the Middle East and Europe. Its critical geostrategic location has been coveted by a never-ending stream of foreign interlopers, from Alexander the Great to the generals of Soviet Russia and the United States. In 1219, Genghis Khan laid waste to the land because its people chose to resist rather than submit. He exterminated every living soul in cities like Balkh, capital of the ancient Greek province of Bactria, home to Zoroastrianism, and a center of Persian Islamic learning. With urban centers devastated, the region became an agrarian backwater under Mongol rule. In 1504, Babur, a descendant of both Genghis Khan and the Persianized Mongol Timur the Lame (Tamerlane), established the Moghul Empire in Kabul and dominated India. But by the early 1700s, the central government in Afghanistan, never strong for long, had collapsed, and much of the region was self-ruled by the Afghans, also known as the Pashtun, fiercely independent tribes who speak

aliba,

a Persian dialect.

The Pashtun, almost all of whom are Sunni Muslim, are divided into a few major tribal confederations, and numerous tribes and subtribes. In 1747, Ahmad Shah Durrani founded a regional empire based on cross-tribal alliances between the Durrani confederation, which provided the political and landowning elite that governed the country, and the larger Ghilzai confederation, which provided the fighters. This was the foundation of modern Afghanistan.

In the nineteenth century, the country became a buffer state in “the Great Game” between British India and czarist Russia’s ambitions in Central Asia. The British gave up trying to occupy and rule Afghanistan after the first Anglo-Afghan War, which ended in 1842, when tribal forces slaughtered 16,500 soldiers and 12,000 dependents of a mixed British-Indian garrison, leaving a lone survivor on a stumbling pony to carry back the news. Still, the British remained determined to control Afghanistan’s relations with outside powers. In 1879, they deposed the Afghan amir following his reception of a Russian mission at Kabul. But in keeping with anticolonial stirrings unleashed in the wake of World War I, the Afghans wanted to recover full independence over foreign affairs, which they did following the Third Anglo-Afghan War from 1919 to 1921. The country remained independent until 1979, when the Russians (Soviets) returned for another go at control, followed in 2001 by the American-led invasion (with Britain as the junior partner) to bring Afghanistan into the Western camp after its brief spell of independence under Taliban control.

All Pashtun trace their common descent from one Qais Abdur Rashid, through his youngest son Karlan. Folklore has it that the Afridi tribesmen of the Karlandri confederation are Rashid and Karlan’s most direct descendants. Although smaller than the Durrani and Ghilzai confederations, the Karlandri confederation, which straddles the present Afghan-Pakistan border, includes the most bellicose and autonomous of the Pashtun tribes. From the time of Herodotus and Alexander, historians have described how the Afridis controlled and taxed the passage of other tribes and foreigners through the Khyber Pass. The British thought the Afridi fearsome characters and fine shots, and so paid them off handsomely, or preferentially enlisted them in the Khyber Rifles and other crack frontier units to help them keep at bay the other Karlandri tribes, most notably the Wazirs of North Waziristan and the Mehsuds of South Waziristan.

Although the Wazirs and Mehsuds were hereditary enemies who constantly fought one another, they would unite in jihad against any foreign attempt to gain a foothold in Waziristan, spurred on by local religious leaders (mullahs) and their martyrdom-seeking students (talibs). The British army missionary, T. L. Pennell, described the situation a century ago in

Among the Wild Tribes of the Afghan Frontier:

Waziristan (the country of the Wazirs and Mahsuds), is severely left alone, provided the tribes do not compel attention and interference by the raids into British territory; which are frequently perpetrated by their more lawless spirits…. [T]ribal jealousies and petty wars are inherent…. Hence the saying, “The Afghans of the frontier are never at peace except when they are at war!” For when some enemy from without threatens their independence, then … they fight shoulder to shoulder, [although] even when they are all desirous of joining some

jihad,

they remain suspicious of each other…. Mullahs sometimes use the power and influence they possess to rouse the tribes to concerted warfare against the infidels…. The more fanatical of these Mullahs do not hesitate to incite their pupils

[taliban]

to acts of religious fanaticism, or

ghaza,

as it is called. The

ghazi

is a man who has taken an oath to kill some non-Mohammadan, preferably a European, as representing the ruling race; but, failing that, a Hindu or a Sikh. The mullah instills in him the idea that if in doing so he loses his own life, he goes at once to Paradise … and the gardens which are set apart for religious martyrs.

1

Other books

Yendi by Steven Brust

Dark Weaver (Weaver Series) by Dena Nicotra

Hearts Left Behind by Derek Rempfer

Claude & Camille: A Novel of Monet by Stephanie Cowell

A Game of Gods: The End is Only the Beginning (The Anunnaki Chronicles Book 1) by Kumar, K. Hari, Harry, Kristoff

Waves of Reckoning (The Montclair Brothers) by Terri Marie

Gio (5th Street) by Elizabeth Reyes

Ember by James K. Decker

The Courage Consort by Michel Faber

Blue Kingdom by Max Brand