Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists (29 page)

Read Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists Online

Authors: Scott Atran

Well after the Madrid attack, the Chinaman’s lady, Rosa, complained that the “Moors” in her neighborhood—a massive, rundown housing project on the edge of Madrid—“fall on their knees in front of my son telling him: ‘You have to be like your father, you have to be like your father.’ They see his father as a martyr.”

12

In one sense, we are greatly overestimating the threat from terrorism, by attributing it chiefly to a resurgent and powerful Al Qaeda. In another sense, we are grossly underestimating the sources of the threat from countless neighborhoods and chat rooms around the world. These numerous but small and scattered sources do not pose a strategic threat to our existence. This reaction to Rosa and the Chinaman’s son is perhaps the most worrisome outcome of the attack. It suggests how hard it will be to get the next generation to turn toward rather than against us. Breaking Al Qaeda is no longer the point.

CHAPTER 13

THE ORDINARINESS OF TERROR

TETUAN. MOROCCO, MARCH 10, 2007

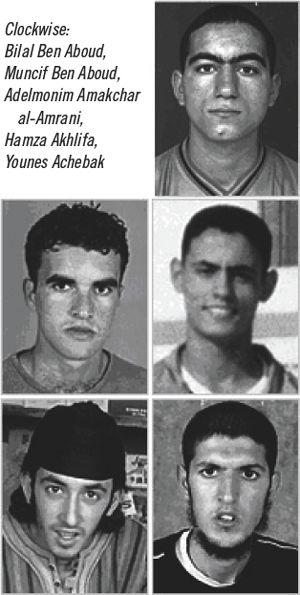

Marc Sageman and I left the Madrid bombing trial and traveled to the Jamaa Mezuak, that backdoor barrio of Tetuán, Morocco, from which five of the seven suicides in the Madrid train bombings came. In Mezuak, a poor but not squalid neighborhood with very little outward sign of any militant Salafi influence, and more cheerfulness than expected, there were few men in skullcaps and even fewer women who were completely veiled.

Martyrs from Mezuak.

We found out about several young men who had volunteered as suicide bombers in Iraq. One of these young men had been identified by DNA analysis provided by the United States to Moroccan authorities. A main facilitator for the pipeline to Iraq seems to have been an imam at the Dawa Tabligh mosque. He was arrested along with some of the wealthy businessmen who donated charity money

(zaqat)

to him that was used to funnel the young men to Iraq.

Two policemen showed up when we went to this mosque, where many of these young men prayed. I had given the camera to Marc and the policemen started to question him. I saw some children next to the mosque and went over to talk to them in my halting Levantine Arabic. Marc would be okay—his nonchalant “who, me?” attitude was already causing the policemen to scratch their heads.

The children were, I guessed, six and eight years old. The younger one had sharp brown eyes under a baseball cap. I asked his name. “Eto’o,” he said (a soccer star from Cameroon who plays on the Barcelona soccer team, Barça); the other one called himself “Ronaldinho” (a Brazilian star on the Barça team). In Tetuán and Tangiers, maybe the richest cities in Morocco, crowds of young men stand around the plazas with apparently nothing much to do; many sport Barça soccer shirts or those of archrival Real Madrid.

The older kid, Ronaldinho, said, “Eto’o is worthless.” An elder standing in front of the mosque was listening and told the children not to lie to me, to show respect, as I was a visitor, a guest in the neighborhood.

A teenager came over, smiling. Nice kid. He rolled a hashish cigarette. The younger boy, Eto’o, offered it to me. I said, “I don’t smoke,” and the teenager reprimanded Eto’o. The teenager asked me if I wanted tea. Eto’o broke in and said, “I’ll bring it, give me some money.” The teenager again yelled at Eto’o.

Then Eto’o pulled on my hand: “Take me to Spain.” I asked if they knew Spain. “Sure,” said Ronaldinho, “we lived in Madrid.” I started leading Eto’o downhill toward Marc and the police, laughing and saying, “We’re going to Spain now.” Eto’o said, “Good, good.”

“But we’ll have to swim,” I told him. And he yanked his hand away and ran back up the hill.

I went back up the hill too. “Give me money to buy a bicycle,” Eto’o said, his hand out. Ronaldinho chimed in, “Yes, give him the money to buy a bicycle.” I said, “Sure, but I’m so tired of traveling that I need a plane of my own, so if you’ll help me get a plane first, then I’ll buy a bicycle.” “Good, good,” said Eto’o, “We take the plane (and then he swept a flat hand, palm down) and

whoooosh!”

he expired with evident glee, “into the White House. I’m Osama Bin Laden!”

“But I thought you said you were Eto’o.” I frowned in mock puzzlement.

“Mmm.” Eto’o nodded, closing his eyes, scrunching up his nose, and puckering his lips as if thinking hard. “Osama is

akbar.”

Osama is bigger.

Marc had somehow gotten free of the policemen, who were standing nearby and still trying to figure out what to do about us. He sauntered over to me and the children, and I told him about the conversation. “A soccer star or Osama?” Marc said. “That’s maybe the big question for this whole generation.” Who to be?

JAMAA MEZUAK, NOVEMBER 2008

Ali is a deeply religious man who owns the Cyprus barbershop just off Mamoun Street in the heart of Mezuak. He worries what will become of the young people in the neighborhood.

“So what made those who went and died in Madrid and Iraq choose violence?” I asked.

“They were victims, all of them, even Jamal Ahmidan [the Chinaman]. They just didn’t have a true Islamic culture to make wise decisions. Most of them did some sort of smuggling. Almost everyone does some of that. For money. But that’s not what took them down the path of violence. It’s the false teaching: of the

Salafiyah

jihad of the

Takfiri,

of the

Khawaraj

[“outsiders,” those who have gone away from the true path of the Prophet and his descendants]. They’re all the same, preaching bizarre things and profiting from the ignorance of the young. In [public] school there are only two hours of Islamic teaching in a week. People need more.”

“Did you know them well? The ones who died in Madrid and the ones who went to Iraq?”

“Most of them. Jamal didn’t come here to cut his hair, and the Oulad Akchas had moved out of the neighborhood, but the others came here.”

“Tell me about Kounjaa’.”

“Kounjaa’ kept to himself. He didn’t talk much. Almost never smiled. I used to give him a Jontra for twenty dirham [about two dollars].”

A client on the next stool explained: “That’s the haircut of the American John Travolta.”

Ali nodded. “Kounjaa’ wanted to be a serious Muslim but got caught up with the wrong people,” he said. “But he wasn’t odd at all, just serious by nature. He had a good soul.”

“That’s what Rifaat’s father, Ahmed, a teacher at the nearby [elementary school], also said about his son.”

“He’s right.” Ali nodded. “Rifaat was delicate. Kounjaa’ protected him and Rifaat trusted him. Both were good, caring people. I don’t know how they got mixed up in Madrid. Maybe money was involved. It couldn’t have had anything to do with Islam. False prophets may have lured them because they didn’t have a real Islamic education.”

I thought,

How often I’ve heard people, of whatever religion, explain religion-inspired acts they don’t approve of as not coming from “real religion.”

Religions survive and thrive precisely because they are inherently vague, even contradictory, and therefore forever open to interpretation.

“And what of Kounjaa’s cousin, Hamza?” I asked.

“Yes, Kounjaa’ was his

ibn ammat.

Married to Hamza’s father’s sister’s daughter. Hamza liked the Jontra too. He was upset about Kounjaa’. Then he just stopped coming to get his hair cut. He let his beard grow. For about a year. His hair came down to here [the shoulders]. I knew what that meant. He was going ‘Afghan,’ like Kounjaa’. I talked to Hamza’s brother:

Balak

[Be careful]. Then, one day, Hamza cut his hair and beard, like they all do, just before going off [to become martyrs]. The same for Younes [Achebak] and Bilal [Ben Aboud] and Amakchar [Adel-monim al-Amrani].”

Ali stopped cutting the hair of his young client, to whom he was giving a bowl-like

coptasa

cut. “What can violence do for any of these young men? To kill innocents is not the path of the Prophet. It is the path to the gates of hell.”

The

caid,

who is the local representative of the Ministry of the Interior, has a man who is his eyes and ears in each neighborhood, called the

muqqadim.

Mezuak’s muqqadim came into the barbershop along with two members of the Renseignements Généraux, police intelligence. They were all dressed in black leather jackets. I silently chuckled at the sight, remembering how the tails they’d put on me the last time I visited Mezuak were easily spotted, especially in the summer when leather made them sweat like penguins in July at Coney Island. This time I had official government permission to talk to people. These guys were just checking up. The muqqadim was a nervous and wary man with hunched shoulders and arms lost in an oversize coat; with his deep-set eyes and a drooping mustache, he looked like a cross between a dachshund and bloodhound. The other two were younger and more relaxed; they smiled at me with a cool stare. So I shook hands with all of them.

“We were talking about Amakchar,” I told the muqqadim. “Ali says he wasn’t really part of the group.”

“His father deals in sheep. He doesn’t have money,” the muqqadim said. “He’s a simple man and ashamed of what his son did. You can meet him if you want.”

“Maybe another day.” I had to figure a way to meet him without the muqqadim being around, but these guys always seemed to catch up with me pretty fast.

“Amakchar was a smuggler,” the muqqadim announced.

Perhaps 25,000 people cross from Tetuán into Ceuta every day, only some of them legally. Like Jamal Ahmidan, Amakchar would float contraband in tires and plastic bags between Ceuta and Tetuán along the Mediterranean coast. Sometimes people drown doing this. More often, the goods drop to the bottom of the sea. No one gets very rich this way.

I mentioned that the Chinaman tried to smuggle hashish this way after he got out of jail and before returning to Spain. But he lost the load in the water.

“Many people do this,” the muqqadim said. “But smuggling is a way of life here. We don’t punish people for that.”

“Even drugs?” I asked.

“At least hashish. No one here thinks it’s a crime. Actually, people tend to like smugglers and drug runners because these are the people who often give the most charity to the mosque and needy, and they give out the most meat in the neighborhood during the Feast of Eid.”

“Sounds like the Mafia,” I said.

“No, no,” the muqqadim said defensively. “Here many normal, ordinary people do such things every day. And they don’t tolerate violence. We don’t tolerate violence.” The two police intelligence officers nodded in agreement. “Violence is rare and we deal with that harshly. Heroin and cocaine are recent here. We don’t like it. Violence comes with it. These drugs, we want to get rid of.”

I asked the muqqadim if any of the young men who went to Iraq were captured or returned.

“No, they’re all gone. After they called their parents to say they were going to become martyrs, none of their parents received word. We think they’re all dead.”

At the headquarters of the Direction des Affaires Générales, the administration for the Ministry of the Interior that provides the caids and muqqadims, much like the French prefectures, Amakchar’s mother waylaid the muqqadim.

“I hate the name Amakchar,” she said. “I’m ashamed, so ashamed of what he did. Forgive me.”

“Why do you say that?” the muqqadim said consolingly. “It’s not your fault.”

“So you will give my other son a residency card?” she pleaded.

The muqqadim explained to me that Amakchar’s younger brother is fifteen and, like every young man, will soon need a residency card.

“Of course, we’ll take care of it. Just make sure the papers are in order.”

I started talking to a young woman sitting in the office of the caid of the caids, the director of the Tetuán bureau of the DAG. She was a new caid, one of the first batch of female caids in Morocco, all of whom had graduated just two months before. All caids must have a doctorate or be enrolled in a doctoral program. She had a doctorate in jurisprudence. I asked her about the role of the family in these cases:

Other books

Heather and Velvet by Teresa Medeiros

Dead People In Love (Haunted Hearts) by Ramer, Edie

Bringing Him Home by Penny Brandon

Jacob's Coins: A Cozy Ghost Mystery (Storage Ghost Mysteries Book 1) by Larkin, Gillian

Cold War by Adam Christopher

Mother Daughter Me by Katie Hafner

A Daughter's Perfect Secret by Meter, Kimberly Van

The High King of Montival: A Novel of the Change by S. M. Stirling

Rosemary's Baby by Levin, Ira