Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists (24 page)

Read Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists Online

Authors: Scott Atran

In the early 1990s, these militant Islamists formed a support network for jihadi fighters in Bosnia and provided them with financing, shelter, sanctuary, and medical care. In 1994, they formally organized themselves, taking the name Soldiers of Allah, under the leadership of Setmarian, Yarkas, and Palestinian preacher Anwar Adnan Ahmed Saleh (Sheikh Saleh). A year later, Setmarian went to London to edit

Al Ansar,

the newsletter of the Algerian Groupe Islamique Armé, under the leadership of Abu Qatada, a Palestinian known as Al Qaeda’s spiritual leader in Europe. (After 9/11, police in Hamburg found eighteen tapes of Abu Qatada’s preachings in Mohammed Atta’s apartment there.)

Sheikh Saleh went to Jalalabad, Afghanistan, to establish links with Al Qaeda, particularly with Abu Zubaydah, the senior facilitator for Qaeda’s operations. (Abu Zubaydah was captured in Pakistan after 9/11, water-boarded and broken, then sent to Guantánamo.) Saleh greeted and processed volunteers coming to Afghanistan for training. In 1997, Setmarian also came to Afghanistan, and took charge of various Al Qaeda training camps, often quarreling over how others handled things.

Meanwhile, in Spain, Yarkas made contact with Al Qaeda affiliates in other parts of Europe, especially in Milan, Brussels, and London. His group welcomed young jihadis returning from Bosnia, Chechnya, and Afghanistan. The militant radicalism of Yarkas’s group clashed with the religious authorities in their mosques. Sheikh Moneir Mahmoud Aly al-Messery, an Egyptian Salafi who was (and still is) imam of the Saudi-funded Islamic Cultural Center, a monumental white marble building that overlooks Madrid’s M-30 freeway, expelled the Yarkas group in 1995 for preaching violence. The M-30 mosque, as it’s commonly known, is the center of Muslim cultural life in the Spanish capital, and the group’s expulsion amounted to a de facto excommunication from the mainstream Muslim community. Later, the group would “excommunicate” Moneir in turn.

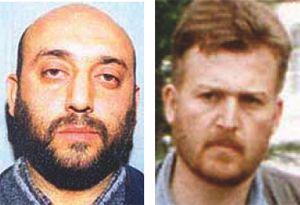

Imad Eddin Barakat Yarkas and Mustafa Setmarian Nasar.

The overt proselytism of the group around Yarkas also attracted the attention of Spanish authorities. As early as 1995, Balthasar Garzón, a judge of the National High Court, ordered surveillance and telephone wiretapping of its leaders. The police succeeded in penetrating it with the help of one of its staff officers, Maussili Kalaji. Kalaji, a Syrian, had joined the Palestinian Fateh, trained in one of its camps, then went on to spy school in the Soviet Union. For some unknown reason, he immigrated to Spain in 1981 at the age of twenty-four and was given political asylum. He became an undercover Spanish policeman and was able to foil a Hizbollah terrorist operation in Europe in November 1989, for which he was decorated. Garzón dispatched him to infiltrate Yarkas’s group. Kalaji opened up a telephone shop, Ayman Telephone Systems Technology, in the Muslim neighborhood of Madrid and became part of the militant network. In a terrible irony, on March 4, 2004, a half dozen hot cell phones were brought into Ayman Telephone Systems to be unlocked. This was duly reported to the police. A week later they were used to detonate the Madrid train bombs.

This Syrian-led militant group was by no means a “sleeper cell.” It was highly visible in order to attract young Muslims, radicalize them to the cause of international jihad, and send them to fight in Bosnia, Chechnya, Afghanistan, and Indonesia. It became a lightning rod for young alienated Muslims seeking a cause. Some were immigrants who had come from Morocco as teenagers and had shown personal initiative by opening up their businesses in the immigrant neighborhood of Lavapies, like Jamal Zougam, with his telephone shop on Tribulete Street, and his half brother Mohammed Chaoui, whose grocery store on the same street sold exotic fruits imported by Yarkas from Damascus. Another new adherent to the group was a Tunisian, Serhane Abdelmajid Fakhet, el Tunecino—the Tunisian—as he became known. An honors economics student who had come to Spain in 1994 for graduate study on scholarship, he would later become one of the two main instigators of the Madrid plot, and its spiritual guide.

3

The dreamer: Serhane Fakhet, el Tunecino (the Tunisian).

Serhane came from a fairly well-to-do family in Tunis. His father worked for the Ministry of Foreign Relations; his mother was well educated and elegant. In the Department of Economic Analysis at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, he specialized in European accounting procedures. The Tunisian’s teachers remember him as sweet, studious, and shy. Young women who were his classmates describe him as not unattractive, but very

incomodo

(uncomfortable) around girls. He had been engaged to be married in Tunisia, but things fell through at the last minute. His friends say he never really got into nightlife in Madrid, preferring to stay home and read. The Tunisian would argue passionately over ideas, especially religion, and seemed to be hypersensitive to any perceived slights against Muslims. One professor recalled him saying: “I’m a good man, an economist, a good student. So why am I not as good as the others? Why are they better than us?”

At first, he wanted to promote Muslim-European relations. He formed a student association, but the other Arab students weren’t all that interested. He tried setting up a radio station, which also fell through. Then he tried selling imported clothes from Tunisia, which didn’t work out. He tried importing candies, and that failed too.

So the Tunisian began spending more and more time at the M-30 mosque, discussing the Koran with a dozen or so others who remember him with fondness. He became the accountant for the mosque’s lucrative halal restaurant and also worked translating Imam Moneir’s preachings. Every day, he and the others played soccer near the mosque; Sheikh Moneir, the imam, refereed. “He loved soccer,” recalls a friend, “he wasn’t a very good player, but he tried hard and sweated a lot.”

In 1998, the Tunisian’s academic scholarship ended, and his request for a renewal was refused—not for lack of smarts, but because he had basically stopped taking school studies seriously. Like many of the young, marginal North Africans in Madrid, the Tunisian started selling stolen goods on the black market in the Lavapies neighborhood of central Madrid, the old Jewish quarter. The police noticed, but did nothing. There are too many like him, they have to live, and they don’t really harm anyone.

The Tunisian moved to Virgen del Coro Street near the M-30 mosque, settling in an apartment owned by Mohanndes Almallah Dabas, the tie-wearing gent who kicked his pregnant wife in the stomach. The Tunisian took in “guests” for weeks and months at a time, extolling the virtues of

takfir wal hijra.

(The phrase, to remind the reader, was first used by a movement founded in Egypt in the 1970s that preached “excommunication and withdrawal” from society, in imitation of the withdrawal of the Prophet and his companions from Mecca to Medina to gather faith and force for a renewed assault on Mecca and the world.)

Taking in fellow travelers and creating a parallel universe devoted to dreams of jihad is commonplace on the road to radicalization. There were usually around five guests in the apartment at any given time, but sometimes there were as many as ten sleeping in a room. The Tunisian would hold court, reading the writings of Bin Laden and showing videos of Muslims being killed in Bosnia, Palestine, Chechnya, and Kashmir. Some of the videos were from Abu Qutada, a friend of Almallah’s brother and also of Bin Laden. One friend remembered the Tunisian booting out someone who refused to wear gloves when handling pork and alcohol in the restaurant where the guy worked. “But he was very generous, always lending others money. He wasn’t so friendly towards Europeans, only his own people.”

At the M-30 mosque, the Tunisian got to know Amer Azizi, a Moroccan student who attended Imam Moneir’s Koran classes. After class, discussion usually turned to politics. But apart from discussions of Palestine, when mostly everyone became agitated, nothing radical or violent was proposed. This soon changed.

The Tunisian went on the pilgrimage (hajj) to Mecca and returned illuminated, interested only in religious matters and righting the wrongs done to Muslims around the world. In October 2000, Sheikh Saleh, one of the original members of the Yarkas group, arranged for Azizi to train in an Al Qaeda camp in Afghanistan. Turkish authorities arrested Azizi on his way there. He was carrying a false passport, a compass, and religious books. Azizi said he was just a religious student on his way to study, and the police let him go. He returned from Afghanistan in the summer of 2001, high as a kite on jihad. He told war stories from Afghanistan and exhorted everyone to join the mujahedin and fight in Palestine and other places. Young people at the mosque, seeing him as an action hero, listened.

That summer, Azizi promoted a series of family picnics at the Parque del Soto by the banks of the Navalcarnero River outside Madrid. The regulars at these “river meetings” included Said Chedadi, Basel Ghalyoun, Dris Chebli, Mouhanned Almallah Dabas and his brother Moutaz, Mustapha Maymouni, the Tunisian, and his close friend Khalid Zeimi Pardo. The children ran around, the women prepared the food, and the friends played soccer and discussed jihad.

4

In August, Jamal Zougam, another picnicker, went to Tangiers to visit Mohammed Fazazi, the fiery Moroccan who had preached at the Al Quds mosque in Hamburg where Mohammed Atta and two of the other 9/11 suicide bomber pilots had been enraptured by Fazazi’s call “to smite the head of the infidels.” Zougam, too, returned with righteous fire. Pardo, though, considered that they were all still merely “Salafist and not adherents of jihad.”

5

Azizi, the Tunisian, and some of the others in Sheikh Moneir’s discussion group stepped up their verbal assault on those, including Muslims, who didn’t follow the Takfiri way as

kuffar

(infidels), subject to

takfir

(excommunication) and execution. They considered Europe Dar al-Harb, the House of War. Imam Moneir pushed back: “Just because someone has a beard, he thinks he’s a sheikh who is knowledgeable and can issue fatwas.” Azizi declared that Moneir, a self-professed Salafi, “is no Moslem,” and angrily stormed out of the mosque with some followers. The Tunisian was among them.

On 9/11, Judge Balthasar Garzón was convinced—wrongly it turns out—that the operation was planned in Spain when he discovered that the last tune-up meeting between Mohammed Atta and Ramzi bin al-Shibh had taken place in Spain in July 2001. He strongly suspected Yarkas and his group of being involved in this planning session and used it as an excuse to arrest the major members of this group. With the information gathered from the extensive wiretapping and Kalaji’s network of informants, Garzón arrested all the core members of Yarkas’s group in November 2001 in Operation Datil. (The Spanish Supreme Court later overturned Yarkas’s conviction for involvement in 9/11.)

Peripheral members who were relative newcomers to the group around Yarkas escaped detection and arrest, including the Tunisian, Zougam, Maymouni, and Mouhanned Almallah Dabas. Others went into hiding. They maintained a low profile, and they were very upset at the arrest of their friends.

The incubation of the Madrid plot by the lesser-known members of Yarkas’s circle began in 2002. The evidence from pretrial testimony, the trial itself, and numerous interviews with friends of the perpetrators as well as various police and intelligence agents strongly indicate that Al Qaeda had nothing to do directly with the plot at any time. No evidence has linked Yarkas or Azizi to the plot, despite frequent speculation about their supposed involvement. None of the discussions leading up to the plot mention Yarkas as a player or even as an idea man. And if Azizi, who eventually made his way to the tribal region along the Afghan-Pakistani border, had really been in the loop, then Al Qaeda would have praised him and promoted him. Ayman al-Zawahiri and others in Al Qaeda repeatedly lauded the attack, and all those involved or accused, but never mentioned Azizi. There have been other attempts to link the Madrid plot to Al Qaeda through the Moroccan Islamic Combat Group, and the Spanish state prosecutor, Olga Sanchez, remains convinced of it. There is nothing substantial in what she offers. More tellingly, there is nothing in the internal dynamics of the plot that requires, or implies, an outside driver.

Other books

Halloween IV: The Ultimate Edition by Nicholas

The Season of Migration by Nellie Hermann

The Train by Georges Simenon

Journey to Munich by Jacqueline Winspear

Madness by Allyson Young

My Life: An Ex-Quarterback's Adventures in the Galactic Empire by Colin Alexander

A Thief in the Night by David Chandler

Jaded Hearts by Olivia Linden

The Ghost of Forever: Gothic Romance Novel by Jane Winston

Learning to Live by Cole, R.D.