Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists (21 page)

Read Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists Online

Authors: Scott Atran

The arrest of hundreds of JI members and associates after the 2002 Bali bombing, including Ba’asyir, and the increasing internal division over the suicide bombing campaign, splintered JI but did not destroy it. The traditional JI hierarchy, which had been only peripherally related to the bombing operations, lost any remaining relevance. Counterterrorism operations after Bali also fragmented the personalized networks that had been forged over the years through kinship, training camps, and schools. But the personal connections left in the pieces were sticky enough to reassemble with some new parts for three major suicide attacks: the Australian embassy in 2004, three restaurants in Bali again in 2005, and another assault in 2009 on the Jakarta Marriott and Ritz-Carlton hotels.

Even before Noordin’s death in September 2009, a new coalition began to emerge between newly released prisoners and other JI-linked fugitives, families, and friends. This “cross-organizational Al Qaeda movement”

(lintas tanzim Al Qaeda)

rejected JI’s provisional shift from violence to “outreach,” as well as Noordin’s bombing campaign that was killing Muslims and alienating the public. The new coalition was led by Dulmatin, who had fled to the southern Philippines after the first Bali bombing and then crept back to Indonesia in 2007. With the help of a founder of Ring Banten (Kang Jaja, who had enlisted the suicide bomber for the Australian embassy bombing) and Kompak’s leader (Abdullah Sunata, who had been released from prison in March 2009), Dulmatin worked to set up a secure military facility that would train operatives to assassinate only those who stood in the way of establishing an Islamic state. The group followed the line of the Jordanian cleric Abu Mohammed al-Maqdisi, who preached that jihad mustn’t victimize innocent Muslims and must go hand in hand with religious outreach. Al-Maqdisi had mentored the Iraq-based jihadi leader Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, but broke with him for the same reason that Dulmatin’s coalition refused Noordin’s tactics. Although Dulmatin and company admired Noordin and included some of his close associates (Ubeid and Urwah), they thought that he had no clue how to establish an Islamic state beyond preparing for the next attack.

14

Fortunately, local police stumbled on the group’s training facility just as it was being set up in Aceh in February 2010. In March, the national police strike team killed Dulmatin at an Internet café near Jakarta, and slew Jaja and several others in Aceh. Ubeid and some training leaders were arrested in April. Even more were killed and arrested in May, apparently still bent on a Mumbai-style rifle-and-grenade assault on President Yudhoyono and other dignitaries (scheduled for Independence Day, August 17, with some hint that the plotters might have tried stirring up things to coincide with President Obama’s planned visit to Indonesia).

Today, with Hambali in American hands, with Noordin and Dulmatin dead, all eyes are understandably back on Ba’asyir, who continues to preach confrontation with the West while studiously avoiding direct support for violence. In the aftermath of the Bali plot, Ba’asyir was sentenced to three years in prison for “blessing” bombing operations, though his sentence was later reduced to eighteen months. Today, Ba’asyir is free and unbending. As he said in my interview with him before release from his well-tended quarters in Jakarta’s Cipinang Prison:

Allah’s law can’t be under human law. Allah’s law must stand above human law. All laws must be under Islamic law. This is what the infidels fail to recognize…. There will be a clash between Islam and the infidels. There is no example of Islam and infidels, the right and the wrong, living together in peace…. They have to stop fighting Islam, but that’s impossible because it is

sunnatullah

[destiny, a law of nature], as Allah has said in the Koran. They constantly will be enemies.

15

Ba’asyir’s moral acceptance of the Bali bombing, his uncompromising attitude toward all but the strictest forms of Islam, and his ruling that “Democracy is prohibited” suggests little chance of coming to terms with the committed remnants of JI. Churches in Indonesia, which Ba’asyir and others claim have no right to exist, continue to receive bomb threats.

16

The peaceful struggle must be for the goodwill of the next generation of Muslims in Indonesia and elsewhere. Ba’asyir and company are well aware of the stakes. To this end, Ba’asyir and several former graduates of his Al-Mukmin school have started a business to win young minds and hearts with shops that offer books, DVDs, T-shirts, and other paraphernalia that sport heroic logos like “Giants of Jihad,” “Waiting for the Destruction of Israel,” and “Taliban All Stars.”

17

CHAPTER 10

THE JI SOCIAL CLUB

Knowledge of the interconnected networks of Afghan Alumni, friendship, kinship, and marriage groups was very crucial to uncovering the inner circle of Noordin.

—GENERAL TITO KARNAVIAN, HEAD OF INDONESIAN POLICE

STRIKE TEAM THAT TRACKED DOWN NOORDIN MOHAMMED

TOP (PERSONAL COMMUNICATION, DECEMBER 10, 2009)

LESS THAN MEETS THE EYE: JI AND AL QAEDA

The Bali bombing is viewed in some quarters as funded and planned by 9/11 mastermind Khaled Sheikh Muhammed in coordination with JI CEO Hambali (who since his days in Afghanistan fighting the communists had presumably served as the principal liaison between Al Qaeda and the group that would form JI). At a hearing in the U.S. military detention center at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, in 2007, Mohammed claimed credit for the Bali operation as his.

1

But Nasir Abas’s version of a JI hijacked by Hambali, and President Bush’s description of Hambali at the time of his capture in 2004 as “a senior Al Qaeda leader [and] close associate of September 11 mastermind Khaled Sheikh Mohammed,”

2

would seem to give equal importance to Hambali as an Al Qaeda operative.

In fact, Mohammed and Al Qaeda had no evident operational input or control in the Bali plot. And in all the talk about Hambali, Zulkarnaen’s central role as the chief strategist of JI’s radical militant group is often overlooked. The almost exclusive focus on Mohammed and Hambali may be partly an artifact of their high-profile captures, their extroverted personalities, and the tendency to overextend stories about what is in hand, or to make up stories, to fill in the gaps.

Mohammed did not join Al Qaeda until late 1998 or early 1999.

3

Only with his success in 9/11 did he rise to the top of Qaeda’s heap (and to the top of the U.S. media heap, with news last fall that he would be tried for his alleged role in 9/11 in New York). Before then, Qaeda’s principal connection to JI was through Abu Hafs al-Masri (Mohammed Atef), a former member of Ayman Zawahiri’s Egyptian Al-Jihad and Qaeda’s military leader.

Hambali’s importance in JI and his links to Mohammed and Al Qaeda have also been overblown, especially in the years prior to the Bali bombing. JI’s wily and furtive military leader, Zulkarnaen, had a higher position in JI and closer contacts to Al Qaeda than did Hambali in the 1990s. According to Nasir bin Abas, Zulkarnaen was always considered the head of the Afghan veterans, a source of prestige and status on a different plane than his formal position as military commander. All militant activities carried out by Afghan Alumni had to be cleared with him.

4

THE AFGHAN ALUMNI AND THEIR ACCOMPLISHMENTS

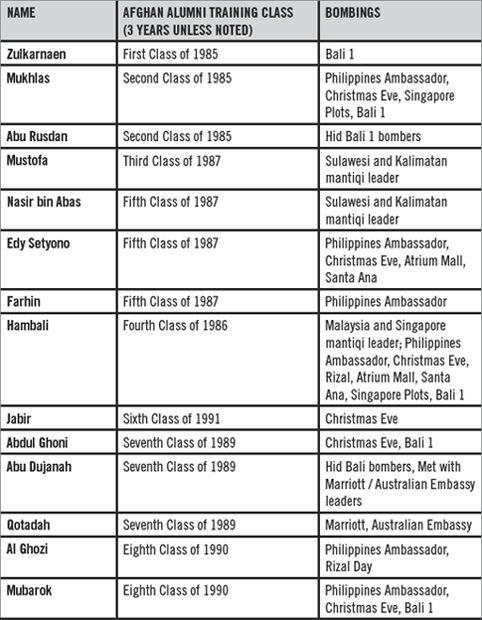

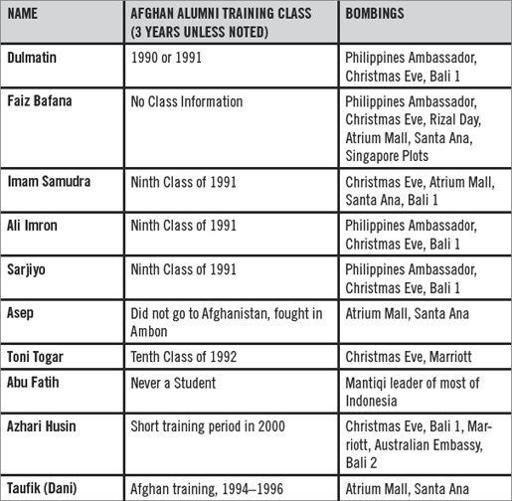

Below is a chart that outlines the most high-profile of the Afghan Alumni and the bombings they were involved in, as well as any role they had in JI’s mantiqi organization:

Bombings

Philippines Ambassador’s Residence, 2000

Christmas Eve, 2000

Rizal Day, 2000 (bombings at Metro Manila in the Philippines on December 30)

Atrium Mall, 2001 (Atrium Senen shopping mall bombing in Jakarta on August 10)

Santa Ana, 2001 (bombing of Catholic Santa Ana church and nearby Protestant church, east of Jakarta, July 22)

Bali 1, 2002

Jakarta Marriott. 2003

Australian Embassy, 2004

Bali 2, 2005

There’s no evidence that Hambali interacted with Mohammed at Saddah, the Afghan mujahedin training camp located in Pakistan near the Khyber Pass, though both were there (as were hundreds of others). It is possible that Hambali met Mohammed in Malaysia in 1996 when the latter visited Sungkar and Ba’asyir at Mukhlas’s boarding school, Lukman Al Hakiem. But Mohammed mentions no noteworthy encounters with Hambali before 2000.

In 1997 Sungkar and Ba’asyir visited Al Qaeda leaders in Afghanistan, who had recently relocated there from Sudan. The goal at the time was to prepare the way for JI members to get training in Qaeda camps. By then Zulkarnaen, who was arguably the third-most influential member in the JI hierarchy after the two religious leaders, was back in Malaysia, occasionally lecturing at Lukman Al Hakiem and planning the coordination of training and military activities with various jihadi organizations, including Al Qaeda in Afghanistan and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front in the Philippines. In August 1998, Sungkar and Ba’asyir called upon Darul Islam leaders and others in the region to join with them in support of Bin Laden’s fatwa proclaining “the Muslim world’s global jihad.”

5

Around this time, Zulkarnaen contacted Abu Hafs al-Masri to arrange training for JI militants in Qaeda camps in Afghanistan. In early 1999, Hambali and Abu Bakr Bafana, who was treasurer for Mantiqi 3, the JI command covering the southern Philippines, Borneo, and Sulawesi, decided to go to Afghanistan to introduce the first two trainees (Zaini and Zamzulri). According to Bafana, he and Hambali were still unaware of Bin Laden’s 1998 fatwa calling for jihad against American, Jewish, and Christian interests,

6

to which Sungkar and Ba’asyir’s letter implicitly referred. Hambali and Bafana met very briefly with a certain “Mukhtar” in Karachi, before continuing to Kandahar. Mukhtar was a nom de guerre for Khaled Sheikh Mohammed, whom Bin Laden had just recently inducted into Al Qaeda to pursue the plot that would ultimately result in the 9/11 attacks. But at this juncture, Mohammed seems to have been no more than Abu Hafs al-Masri’s point man for relaying contacts through Pakistan to Afghanistan. At the time, Ba’asyir’s son, Abdul Rohim, was JI’s chief contact person with Qaeda in Pakistan. Hambali’s younger brother, Gun Gun, would later take over from Abdul Rohim.

Later in 1999, Hambali sent Bafana again to Afghanistan, this time explicitly to plan joint JI-Qaeda operations in line with Bin Laden’s fatwa. Hambali’s initial plan was to attack a U.S. warship in Singapore. He provided Bafana with videotapes of site casings, which he asked Bafana to show to Mohammed. Bafana failed to find Mohammed in Karachi and went on to Baluchistan, where he sneaked across the border to meet Abu Hafs al-Masri at Bin Laden’s camp near Kandahar. When Bafana told Abu Hafs that JI had no suicide bombers, Abu Hafs reportedly responded: “We will provide the personnel. The money we will provide. All you need to look for is the explosive, the TNT, and the transport.”

7

Other books

One Night Only by Emma Heatherington

The Uncertain Customer by Pearl Love

Buttoned Up by Kylie Logan

Caitlin's Choice by Attalla, Kat

Hand of the King's Evil - Outremer 04 by Chaz Brenchley

The Ballad of Rosamunde by Claire Delacroix

Enemy Mine by Lindsay McKenna

No Take Backs by Kelli Maine

It Will Come to Me by Emily Fox Gordon