Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists (18 page)

Read Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists Online

Authors: Scott Atran

The fourteenth-century Muslim polymath Ibn Khaldûn described

fiqh

as “knowledge of the rules of God which concern the actions of persons who own themselves bound to obey the law respecting what is required

(wajib),

forbidden

(haram),

recommended

(mandub),

disapproved

(makruh)

or merely permitted

(mubah)”

Abdullah Azzam’s teachings on

fiqh al-jihad

included topics like “The Islamic Ruling with Regards to Killing Women, Children and Elderly in a Situation of War.” According to Azzam:

Islam does not [urge followers to] kill [anyone among the infidels] except the fighters, and those who supply Mushrikin [pagans] and other enemies of Islam with money or advice, because the Koran says: “And fight in the Cause of Allah those who fight you.”

Fighting is a two-sided process, so whoever fights or joins the fight in any way is to be fought and slain, otherwise he, or she, is to be spared. That is why there is no need to kill women, because of their weakness, unless they fight. Children and monks are not to be killed intentionally, unless they mix with the Mushrikin … we fire at the Mushrikin, but we do not aim at the weak.

Abusing or slaying the children and the weak inherits hatred to the coming generations, and is narrated throughout history with tears and blood, generation after generation. And this is exactly what Islam is against.

Azzam coined the term

al-qaeda al-sulbah,

“the strong base,” to refer to the vanguard of a new global Islamic revolution whose symbols are the rifle and the book. In April 1988, at Geneva, the Soviets agreed to pull out their last troops by February of the next year. Before the Soviet withdrawal was complete, Bin Laden joined forces with the head of Egypt’s Al Jihad, Ayman Zawahiri, and others to form a new al-qaeda vanguard very different from what Azzam had in mind.

6

Bin Laden and Zawahiri disagreed with the limits that Azzam placed on the aims and means of jihad. Azzam was reluctant to harm civilian noncombatants. He wanted to continue jihad against Zionist Jews, Christians who occupied Muslim lands, including Spain and the Soviet republics of Central Asia, and Indian Hindus in Kashmir. But he did not want to fight against Muslims, however secular.

For Zawahiri, however, waging jihad on corrupt Muslim governments was central, especially against the “apostate” Egyptian government that had allied itself with America and made peace with Israel. In November 1989, Azzam and his two sons were killed on their way to mosque services in Peshawar by a massive explosion. Azzam’s son-in-law blamed Zawahiri, but most jihadis I’ve talked to, including Farhin, believe on no evidence that U.S. and Israeli intelligence services, or their local partners, assassinated Azzam.

In

The Looming Tower,

7

a Pulitzer Prize-winning account of the origins of Al Qaeda, author Lawrence Wright observes:

The pageant of martyrdom that Azzam limned before his worldwide audience created the death cult that would one day form the core of al-Qaeda. For the journalists covering the war, the Arab Afghans were a curious sideshow to the real fighting, set apart by their obsession with dying. When a fighter fell, his comrades would congratulate him and weep because they were not also slain in battle. These scenes struck other Muslims as bizarre. The Afghans were fighting for their country, not for paradise or an idealized community. For them, martyrdom was not such a priority.

The Indonesian Afghan Alumni were much closer to the Arab volunteers in this respect than to Afghans. The Afghans resent Arabs, or anyone else, telling them what they should do.

In a letter (authenticated by Indonesian intelligence) sent from Malaysia dated 10 Rabiul Akhir 1419 (August 3, 1998) and addressed to leaders of Darul Islam, Abu Bakr Ba’asyir and Abdullah Sungkar state they are acting on Bin Laden’s behalf to advance “the Muslim world’s global jihad to fight against America” because “the Jews and Christians will never be satisfied until you follow their way of worship.”

NO LAUGHING MATTER

I thought of Farhin telling me of his desire to blow up the beautiful Balinese wedding we had witnessed together, and I weighed that against his sidestepping involvement with the suicide bombing. Abdullah Azzam had helped to instill desire for jihad and martyrdom in Farhin, but not quite Bin Laden’s way. That instinctive shying away from the actual murder,

8

and laughing together over common things, may yield common ground enough to move the path to jihad away from the most extreme forms of violence. Especially if we can learn to take advantage of a recent widening of the breach within the ranks of senior Islamists and jihadis.

9

So, apparently, thinks General Tito Karnavian, leader of the Indonesian national police strike team Antiterrorism Detachment 88, which has tracked down the big players in those JI factions devoted to international jihad. Tito knows Farhin, and has embraced him, as he has Ali Imron, the brother of the executed Bali plotters, Mukhlas and Amrozi. Tito argues along the same lines as senior Saudi and Turkish police intelligence officers that terrorism can be more of a public health issue than a criminal matter, and that treating morally motivated terrorists as common murderers and other criminals may not be the right way to go. Tito points out that Ali Imron has helped to turn more people away from violence than he imagined. But when Tito showed a slide of himself hugging Ali Imron, whose life was spared only because he expressed remorse for his role in the bombing, a top FBI official who was on hand remarked: “Maybe that works. Maybe it’s the smart thing to do. But … can you imagine me hugging Timothy McVeigh? They’d have me hanging by my balls from the dome of Congress!”

At least in Iraq, and now in Afghanistan, U.S. policy has started to shift toward treating terrorism as a social and public health issue rather than a strictly military and police problem. Following the debacle of prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib by U.S. forces, General Douglas Stone took charge of detainees for the Multi-National Force under the command of General David Petraeus. Stone, a mechanical engineer by training, a rancher of Navajo and German descent who was raised partly on an Indian reservation in Arizona, released more than one fourth of the 23,000 detainees under his charge on condition that their families and tribes take responsibility for them. Only a dozen have been recaptured in suspected insurgent activity. Thousands of those still in prison have learned to read and write. Hundreds study science and math, civics and law, Arabic and English, and how to be adept at trades that will support them after release. They play soccer, visit with their families, and discuss how to interpret the Koran they can now read for themselves. But reputation, like life itself, is a complex affair that is difficult to sustain but simple to destroy. With heavy eyes, General Stone told me: “We have turned around 180 degrees to show respect for any of the detainees in our care: respect for the culture, for the religion, and for the history of the place where our compounds are. But what those few did [at Abu Ghraib] will probably be the images best remembered of this war for a hundred years from now.”

At last word, Farhin was selling coconut wood from Sulawesi, tending a small plot of cacao land, and cultivating hothouse ornamental plants. His second wife had delivered their second child. He wanted to improve his Arabic and English, but remained ready to take up arms again “if Muslims are attacked.” I don’t know if he has managed a transmigration to a more peaceful soul or how keen he still is on martyrdom, but at least he seemed to have shied away from killing noncombatants. He even said he is willing to come to America to explain how he sees things and to try to understand what others see. When I brought up this offer, and similar proposals from other jihadis, at the White House, the State Department, the Department of Defense, the Department of Homeland Security, the Senate, the House, and the FBI, some people laughed, others seemed bemused, and most rolled their eyes. It seemed that the idea of talking to our enemies to find out why they are our enemies could only come from Planet Fruitcake.

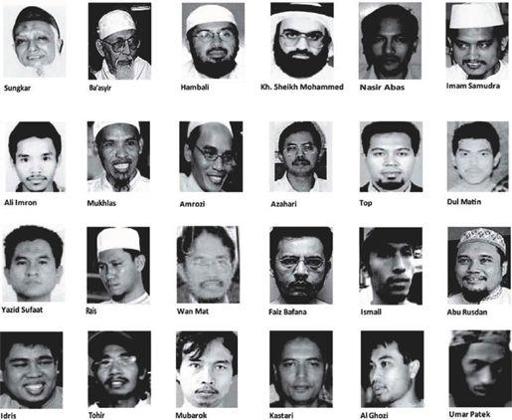

Some key players associated with the Bali bombing.

CHAPTER 9

THE ROAD TO BALI: “FOR ALL YOU CHRISTIAN INFIDELS!”

I

n September 2009, Indonesian security forces killed Noordin Top, number three on the FBI’s most-wanted terrorist list, just behind Osama Bin Laden and his deputy Ayman Zawahiri. Implicated in the region’s worst suicide bombings, including the Jakarta Marriott and Ritz-Carlton bombings in July 2009, Noordin headed a splinter of Jemaah Islamiyah, under his own logo, “Al Qaeda for the Malaysian Archipelago.” He had been on the run since the 2002 Bali bombing. Although he did not play a large role in that attack, he and fellow Malaysian and old college chum Azhari Husin soon afterward replaced Hambali (a veteran of the Soviet-Afghan war and instigator of the Bali bombing plot), Mukhlas, and Samudra as the central figures of Indonesian terrorism.

After Azhari’s death in a shootout following the second Bali bombing in 2005, Noordin’s reputation began to assume mythic proportions in jihadi circles. His many amazing escapes signaled to his sympathizers that God had blessed his Qaeda-style agenda for international jihad against Western interests. Noordin vowed that he would gladly embrace martyrdom and never be taken alive. In jihadi circles, his death, too, is now the stuff of legends.

Noordin’s demise is the culmination of a counterterrorism campaign launched after the first Bali bombing. But success was long in coming. How was a splinter faction of JI able to survive massive manhunts to mount spectacular suicide attacks against Western targets that succeeded, despite their apparent amateurishness, lack of financial means, and decimation of operatives?

JAKARTA, AUGUST 14,2005

Mohammed Nasir bin Abas, the former head of Jemaah Islamiyah’s Mantiqi 3 command for military training and for the territories of Sulawesi, East Kalimantan (Borneo), and the southern Philippines, dabbed at his food in the Indian restaurant and shook his head. “I cannot say that Ba’asyir ordered the Bali bombings,” he said. “But he did nothing to stop Hambali from planning suicide attacks with others and killing civilians, including innocent Muslims. That’s one of the reasons I quit JI. I consider myself a soldier in the defense of Islam. Soldiers fight soldiers, not tourists or other people just because they have a different religion.”

After attending a religious school for two years, Abas met Sungkar, whom he called “a good and charismatic preacher” and who sent him for three years’ training in Afghanistan (Afghan Alumni Class of ‘87) to become an arms instructor and religious teacher. In 1993, when Sungkar and Ba’asyir split from Darul Islam, Abas was asked to take a loyalty oath to the new organization. He became a top JI military trainer but also gave religious instruction. Among his trainees were future Bali bomb plotters Imam Samudra and Ali Imron.

On October 12, 2002, two young suicide bombers, Iqbal and Feri, detonated their lethal charges in the Kuta tourist district of Bali, Indonesia. The terrorists who planned this act counted on Bali’s image as the Western world’s idea of earthly paradise, an undulating island of gentle green curves and human grace. The attack had a message for the Balinese themselves, a Hindu people of great tolerance, that their arrogant indulgence of Western lust and their own sensuality was punishable by death by the militants’ wrathful god. It was also a wake-up call to counterterrorism forces caught unaware that JI even existed.

Over the previous year, Imam Samudra, the field commander of the Bali operation, had assembled five prospective martyrs from the Islamic high schools that dotted the countryside around his hometown of Serang in the coastal region of West Java. It was in West Java that the Islamic insurgent movement Darul Islam (DI) was born in 1949, the year that the Dutch left Indonesia. And it was in a Serang high school in the late 1980s where Samudra fell under the spell of Kyai Saleh As’ad, a former DI commander who had fought with the movement’s leader, S. M. Kartosoewirjo, before the latter’s capture and execution. Later himself on death row for the Bali bombing, Samudra, a former high school valedictorian, remained as committed as ever to Kartosoewirjo’s vision of a pure Islamic state for Indonesia, the region, and eventually the world.

1

Other books

Thornfield Hall by Jane Stubbs

The Book of Forbidden Wisdom by Gillian Murray Kendall

Guilty Until Proven Innocent by Sarah Billington

Mist Over Pendle by Robert Neill

Hopelessly Broken by Tawny Taylor

50 Ways to Hex Your Lover by Linda Wisdom

The Mysteries of Udolpho by Ann Radcliffe

Dark Immortal by Keaton, Julia

The Love Children by Marylin French

Gold Mountain: A Klondike Mystery by Delany, Vicki