Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists (20 page)

Read Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists Online

Authors: Scott Atran

He was a star pupil and gifted teacher from Al Mukmin

pesantren

who joined Sungkar and Ba’asyir in exile in Malaysia in 1985. At Sungkar’s prodding, Mukhlas soon left for Afghanistan to join Zulkarnaen and a growing number of other volunteers to train and fight communists. Another younger brother and fellow Bali plotter, Ali Imron, followed to Afghanistan a few years later and joined Samudra as one of the Afghan Alumni in the Class of ‘91. In 1991, Mukhlas’s family established the Al Islam

pesantren,

which was modeled on Al Mukmin, and considered Ba’asyir its patron.

Ali Imron and his neighbor, another fellow Bali plotter named Mubarok, later became teachers at Al Islam. Ali Imron managed to elude authorities for a time after the Bali bombings with the help of several Al Islam students.

In 1992, Sungkar instructed Mukhlas to set up a new boarding school, Lukman Al Hakiem

pesantren,

in Johor, Malaysia, which followed the Al Mukmin curriculum with the same goal of producing militants for jihad. Sungkar moved nearby to oversee the school and to run a chicken farm, where some of the Afghan Alumni found work. Lukman Al Hakiem quickly became the nerve center of the JI exile leadership.

9

Those associated with the school include Zulkarnaen, Hambali, Samudra, and the three brothers Mukhlas, Amrozi, and Ali Imron. In the mid-1990s, Mukhlas began giving talks on religious education to an informal group of teachers and students at the nearby University of Technology, Malaysia (UTM), in Johor. Three Malaysians from the group soon came into the center of JI’s orbit: Wan Win bin Wan Mat, who lectured in project management, became a Lukman board member and head of the important Johor Wakalah; Azhari Husin, a British-trained engineer and author of books on multiple regression analysis, would become JI’s master bomb maker; and Noordin Top, who taught mathematics and geology, would eventually replace Mukhlas as Lukman’s director.

The radicalization at Lukman Al Hakiem paid dividends in the early 2000s for Zulkarnaen, Mukhlas, and Hambali. The 2000 Philippines Ambassador’s Residence bombing and the 2000 Christmas Eve bombings marked the first time that a core group of JI terrorists gathered together to plan a large-scale action. The ambassador bombing was also the first attempt by JI to create a complex Al Qaeda–style car bombing and would serve as a model for future JI bombings.

For the Christmas Eve bombings, JI operatives placed thirty-eight bombs at churches from northwestern Sumatra, across Java, to the island of Lombok, east of Bali. Although some were duds, most of the bombs exploded, killing 19 people and injuring 120. Like the ambassador bombing a couple of months earlier, the Christmas Eve bombings served as a warm-up for Bali. In particular, the coordination across multiple groups for the Christmas Eve bombings became the model for the Bali bombing, which also involved operatives from Darul Islam and Ring Banten (another radical jihadi organization that had splintered from Darul Islam).

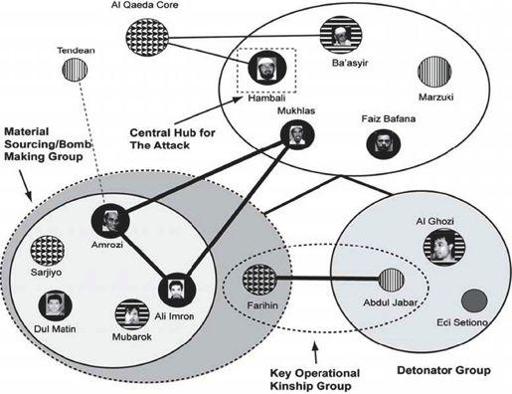

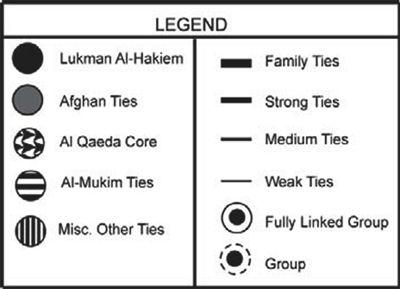

Kin relationships were important for both the ambassador and Christmas Eve bombings. In addition to the key tie between Farhin and the ambassador bombing, three of the participants in both events—Mukhlas, Ali Imron, and Amrozi—were brothers, and all would later take part in the Bali operation. This is representative of a larger trend among jihadis across the world to rely on family and marriage for operations—an important development because as organizations such as JI become increasingly endogamous over time (as friends begin to marry one another’s siblings), they become increasingly bound by a trust that is harder for counterterrorism efforts to penetrate or break.

THE PLOT THICKENS

The Bali bombing planning process started when Hambali convened a meeting of his radical advisers, Mukhlas, Wan Min bin Wan Mat, Azhari Husin, Noordin Top, and Zulkifli Marzuki in Thailand in early 2002 to discuss future bombings. At the meeting, Hambali changed the focus to soft targets, such as bars and nightclubs, and handed out assignments. Noordin and Azhari were to “apply” for funding through Al Qaeda, Mat would arrange the transfer of funds, and Mukhlas would direct the bombing.

Because so many of these men were in hiding from Malaysian and Indonesian authorities, Mukhlas decided to work through other JI operatives in Indonesia. Like Hambali, he avoided the moderate leader, Abu Fatih. Instead he chose to work through the radical Zulkarnaen.

Mukhlas then recommended Samudra to be the field commander for the bombing. At the trials following the attack, Imam Samudra was best known for screaming at spectators, covering his ears to avoid listening to his death-sentence verdict, and generally showing no remorse for his role. When asked about the Australian victims of the bombing, he responded: “Australia go to hell. The Jews and Christians go to hell. Islam will win. Islam will win. Allahu Akbar.”

10

Philippines ambassador’s residence bombing network in 2000).

In mid-August, Zulkarnaen convened a meeting at a house rented by Dulmatin, a Lukman teacher who would go on to trigger one of the bombs with his cell phone. Present were Amrozi, Ali Imron, Abdul Ghani, Mukhlas, Umar Patek, Idris, and Imam Samudra. According to Ali Imron, it was here that roles for the bombing were assigned and finalized: Dulmatin, Abdul Ghoni, Umar Patek, and Idris were responsible for making the bombs. Amrozi and Ali Imron procured the car and fertilizer, and arranged transportation. Idris helped with the transportation, arranged accommodations, and also obtained the U.S. dollars for Amrozi. Details such as fake IDs, destruction of serial numbers, and timing of bombs for maximum damage were discussed after the meeting. Iqbal, as well as Abdul Rauf, Andi Hidayat, Andri Octavia, Heri Hafidin, and Junaedi operated under the tutelage of Samudra.

From here, the mission planning was put into overdrive. Ali Imron, Umar Patek, Abdul Ghoni, and Dulmatin mixed and built the bomb with the guidance of Azhari Husin. Idris handled all logistical issues, Mubarok provided logistical and transportation services, and Imam Samudra directed the ongoing operation. Samudra and Ali Imron began casing areas—Denpasar, Nusa Dua, Sunar, and Kuta—provisional targets were Sari Club and Paddy’s Pub on Jalan Legian. A Bali native whom Dulmatin introduced to the group named Mayskur was added to the network for a key logistics role (as “tour guide for Bali”) at the last minute.

But Samudra had managed to alienate a large part of the team as a result of his abrasive, authoritarian personality. Amrozi later noted that he felt like a busboy, as he was excluded from all decisions and bomb-making activities while in Bali. Not surprisingly given his personality, Samudra was only able to convince one protégé, Iqbal, to become a suicide bomber. As a result, Dulmatin, one of the bomb-makers, was forced to recruit Feri to be the second suicide bomber. Samudra also never bothered to check whether the bombers could drive a car (they couldn’t). So at the last minute, Ali Imron had to teach one of them how to drive.

Somehow amid this comedy of errors, the group was able to transport the bombs and suicide bombers to the nightclubs, and on October 12 Feri and Iqbal detonated the bombs at Paddy’s Bar and the Sari Club.

AFTER BALI: THE DEVOLUTION OF JI

On August 11, 2003, the CIA, working with Thai intelligence, captured Hambali in a Muslim enclave in the ancient Thai capital of Ayutthaya, a sleepy town north of Bangkok. His arrest and subsequent transfer to Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, finally started to undo the Bali bombing network that had begun forming years before. But Azhari Husin and Noordin Top picked up the pieces to build a new, even more personalized network of family, friends, and fellow travelers in jihad.

At approximately 10:30

A.M

. on September 9, 2004, a car bomb detonated outside the front gates of the Australian embassy in Jakarta, Indonesia, killing eleven people and wounding hundreds. The massive explosion created a ten-foot-deep crater, mangled the embassy’s gates, and shattered windows in nearby buildings. The Australian embassy bombing was the first JI bombing led entirely by Noordin Top and Azhari Husin, without funding or direction from Hambali.

Now Noordin and Azhari were the two most wanted men in Southeast Asia. For the Australian embassy attack they had plied the traditional JI network for operatives (particularly from a handful of radical madrassahs). But many members and sympathizers began to question the wisdom of using suicide bombings to directly challenge Western interests and the Indonesian state before they had the support of the population. And these attacks, which also killed Muslims, only alienated that population.

So Azhari and Noordin were compelled to rely more heavily on fringe elements of the Muslim “charity” organization Kom-pak, on Darul Islam, and on Ring Banten, the DI-linked group in the Serang countryside. To a good extent, these connections were already part of the personalized networks of the principal Bali plotters, but because many other JI members refused to help out, Azhari and Noordin had to tinker in creative ways to add enough pieces and repair their networks to get the suicide bombing campaign rolling again. Their acolytes set up a training camp in West Java to train the bombers who would take part in the embassy operation. A pair of religious students, Ubeid and Urwah, assisted in setting in motion a series of relationships with anyone who could acquire explosives and make bombs.

Indonesian security forces arrested several people in the group, disrupting the planning of the embassy operation before it was implemented. JI’s ability to implement the attack in the wake of these arrests attests to the resilience of its family-and school-based network. The final bombing team included Noordin, the director of operations; Azahari, the chief bomb maker and second-in-command; Rais, the field commander; and Heri Golun, Jabir, Heri Sigu Samboja, Apuy, and Achmad Hasan as team members.

The 2004 Australian embassy bombing would serve as the template for the decentralized structure that Noordin and Azhari would use to lead the 2005 Bali bombings, striking the same city as in 2002 and killing twenty people and injuring over a hundred others. But even from his Indonesian prison cell, Mukhlas would smuggle out messages to Noordin, who continued to seek out his old teacher for spiritual guidance. A corrupt prison warden smuggled in a laptop for Samudra, who used the prison’s wireless connection to converse with some of the Bali 2005 plotters.

EMBERS

After the American decimation and scattering of Al Qaeda forces in Afghanistan in 2001–2002, and after the massive arrests of JI leaders and members in 2002–2003, the most violent remnants of JI lacked the financial and logistical means to carry on large-scale attacks by themselves. New trainees were now asked to pay for their own training, which meant fewer trainees. (For the Mount Ungaran training, Noordin could only find eight people ready to pay for themselves.)

11

Increasingly Azhari and Noordin looked for new sources of funding and personnel.

They sought out people to do

fa’i,

or robbing non-Muslims for a Muslim cause, because there weren’t enough outside funds or members’ contributions.

12

Toni Togar had turned to

fa’i

to help Noordin pay for the Marriott bombing—he robbed a bank in Medan. Imam Samudra had previously resorted to

fa’i

when he ordered his Serang group of candidate martyrs to rob a Chinese goldsmith’s shop a year before the Bali bombing. But gaining experience rather than money was the aim of that exercise. (As Azhari reportedly put it, “there would always be donors,” especially among wealthy Malaysians, to fund operations.)

13

With Azhari and Noordin,

fa’i

implied involvement with petty criminals, not that the new JI attack leaders themselves had any mundane, criminal ambitions. It’s simply that the success of counterterrorism actions against JI and Al Qaeda required new forms of alliance and adaptation, taking advantage of new avenues of opportunity and hitherto unused niches.

Other books

Getting Things Done by David Allen

Lieutenant (The United Federation Marine Corps Book 3) by Jonathan P. Brazee

The Man Within by Leigh, Lora

Kornwolf by Tristan Egolf

Cherie's Silk by Dena Garson

Sand Witches in the Hamptons (9781101597385) by Jerome, Celia

Vesik 3 Winter's Demon by Eric Asher

Zeuglodon by James P. Blaylock

My Life With Deth by David Ellefson