Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists (34 page)

Read Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists Online

Authors: Scott Atran

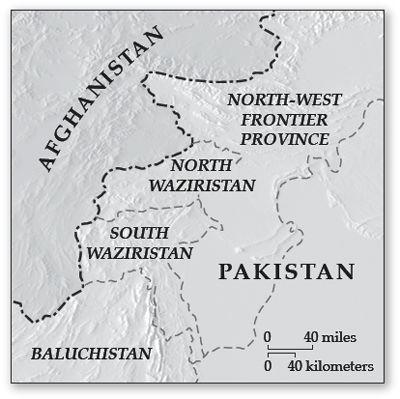

After much bloodletting, the British realized that any attempt at permanent occupation or pacification of the warring tribes would only unite them, and that it would be nearly impossible to defeat their combined forces without much greater military and financial means than Britain could afford. So Britain finally settled on a policy of containment, institutionalized by Lord Curzon, Viceroy of India. Having come to India in 1899, shortly after one bad spate of Wazir and Mehsud uprisings, Curzon had established the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP) as a buffer zone, splitting the tribal areas between Afghanistan and that part of British India which is now Pakistan. “Our policy was to interfere as little as possible with the internal organization and independence of the tribes,” he said, and by

control and conciliation

“endeavour to win them over” to secure the frontier.

2

Control involved withdrawing British forces from direct administration of the frontier region, including parts of Afghanistan, “for which our Regular troops were neither recruited nor suited,” Curzon noted. Some well-defended outposts would remain to protect the roads that were being built to help integrate and secure the tribes through commerce (Afghanistan still has no railroad network). But the government would most rely on “forces of tribal Militia, levies and police, recruited from the tribesmen themselves,” though trained and directed by English officers. Conciliation meant subsidizing the “friendlies” to hold off the “hostiles” until they, too, realized that it was in their own self-interest to accept British bounty for abandoning their traditional “outlaw” ways, or at least raids against British territory.

Map of Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas.

After the partition of India in 1947, the successor state of Pakistan continued the policy of co-opting “friendlies” with various incentives (arms, money, political position) to hold off the hostiles. Going a step further, the country’s founder, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, decided that concentrations of regular troops from the brigade level up would be evacuated from Waziristan and the other Federally Administered Tribal Areas wedged between the NWFP and Afghanistan. He aptly called his plan Operation Curzon.

3

THE THIRTY YEARS’ WAR AND THE RISE OF THE TALIBAN

The Pashtun comprise over 40 percent of Afghanistan’s population, about the same as a century ago. The Tajiks contribute almost 30 percent; the Hazara and Uzbek each just a bit less than 10 percent. But the Pashtun have long dominated the country, politically and militarily. Except for a nine-month interlude in 1929, Durranis lorded over the country until the communist takeover in 1978 that killed Mohammed Daoud Khan.

Daoud’s government and its predecessor had been very wary of introducing reforms, especially concerning the status of women. They feared the kind of unrest that had unseated Amanullah, the Durrani amir who had fought the British in the third Anglo-Afghan War to gain full independence for his country in 1921. Inspired by the policies of Turkey’s secular reformer Kemal Ataturk, Amanullah embarked on an ambitious modernization program, which resulted in a rebellion of Pashtun tribal and religious leaders that removed him from the throne in 1929. He was initially replaced by an ethnic Tajik, whom the Pashtuns came to view as an usurper. So the tribesmen threw their support behind one of Amanullah’s generals, Zahir’s father, who had been exiled by Amanullah for questioning the wisdom of the amir’s policies. He sacked Kabul in 1929 with mostly Wazir and Mehsud tribal forces and became king. Despite the assassination of Zahir’s father in 1933, and Daoud’s coup in 1973, Afghanistan enjoyed half a century (1929–1978) of relative peace and accommodation between the central government and the tribes.

This was followed by a Thirty Years’ War that began when the communist government threw caution to the wind and immediately proclaimed a secular socialist government that tried to force far-reaching land reforms and push programs to better the status of women. The tribes rebelled, the regime was about to collapse, and so the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in December 1979 to “save socialism.” The radical reforms were rescinded, but the Soviet occupation generated even greater tribal resistance. The call to jihad brought in Muslim volunteers from around the world, and financial and logistical support from Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the United States. In 1980, U.S. National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski, swathed in a Pashtun turban and waving an AK-47 near the Khyber Pass, exhorted the mujahedin to fight “because your cause is right and God is on your side…. Allahu Akbar!”

4

Pashtun traditionally identify themselves first and foremost by

qawm,

which Westerners usually translate as “clan,” a subtribal identity traditionally based on kinship and residence. In the past, male members of each qawm were invariably blood-related. But the change toward a market economy has somewhat lessened the strict importance of kin relations and encouraged new qawms based on patron-client economic networks.

5

More recently,

qawm

has come to mean any segment of society bound by solidarity ties, whether by kinship and residence, occupation and patron-client relations, religious interests, or dialect. A qawm can involve a varying number of individuals, depending on context and situation. During the Soviet-Afghan War, as in the present Taliban insurgency, the notion of

qawm

became even more ambiguous and flexible to allow for strategic manipulations of identity to carry out group actions in shifting contexts.

6

But especially among the hill tribes, qawms are still heavily family-oriented and much the primary reference groups for military action.

The mujahedin fought primarily to defend their faith and community against a hostile ideology, an oppressive government, and a foreign invader: “It was a spontaneous defense of community values and a traditional way of life by individual groups initially unconnected to national or international political organizations.”

7

Their tactics differed from place to place, qawm to qawm. Although few guerilla commanders were military professionals, Afghanistan under Daoud and Zahir had a conscript army in which most twenty-two-year-old males served two years. The tribes scorned professional soldiers as mercenaries, but they had supported the draft because it provided basic military know-how that helped boys become men even in peacetime. Friendships made during military service also later eased cooperation among guerrilla groups.

8

Over the course of the war, state institutions decayed. But there were also profound changes in local communities that helped pave the way for the emergence of the Taliban after the war. The old elite of large landowners and tribal elders ceded to a new cadre of younger military hotshots from less prestigious backgrounds who began to play an important role in the administration of community life. At the same time, there was a sharp expansion of the role of the Islamic clergy

(ulema).

Clerics with an advanced madrassah education

(malawi)

and knowledge of Sharia enjoyed greater prestige than the boorish mullahs. The ulema were able to leverage this prestige into political influence that cut across tribal boundaries by networking with Pakistani political parties that funneled money and supplies to the mujahedin (some provided to them by the United States via Pakistani intelligence) and by morally restraining military commanders from arbitrary actions that benefited only themselves and their kin.

9

Soviet forces withdrew in February 1989. But only after the Soviet Union collapsed, ending all outside assistance to a local client regime that was holding on by the skin of its teeth, did Kabul fall to the mujahedin forces, in April 1992. The mujahedin immediately took to fighting among themselves for control of the city and the countryside. A state of near-anarchy prevailed as demobilized and penniless warriors became outlaws who preyed even on women and the weak. Reacting to a series of outrages around the southern city of Kandahar, a small group of religious students

(taliban),

led by their teacher, Mullah Omar, killed the worst of the bandits in 1994 and proclaimed a new movement, the Taliban, that would unify the country by using the sword of pure virtue to cut away all vice (including the playing of music, shaving the face, and educating women). With Pakistan’s aid, their power spread to other Pashtun areas. Taliban forces took Kabul in 1996 (although Mullah Omar chose to remain in Kandahar) and extended control over the whole country except the Tajik-controlled northeast by 1998.

Final victory came to the Taliban on September 9, 2001, when, with Al Qaeda’s assistance, a suicide bomber posing as a journalist managed to kill Ahmad Shah Massoud, the legendary Tajik commander of the Northern Alliance known as the Lion of Panshir. Two days later, Al Qaeda attacked the United States, apparently without informing the Taliban leadership of its plans. Most probably, Bin Laden assumed that by helping the Taliban to win Afghanistan, Qaeda was free to use the country as its base from which to launch attacks. Taliban religious leaders, however, judged that Bin Laden had abused his status as a “guest” in the country and urged Mullah Omar to “invite” Bin Laden to leave.

The United States would not wait upon such customs, which were judged insincere (but wrongly so, as we’ll see). With U.S. air and special forces in support, the Northern Alliance entered Kabul in November 2001. In Afghanistan, a governing coalition rapidly emerged of Afghanistan’s Durrani president, Hamid Karzai, and the Tajik-led successors of the U.S.-backed Northern Alliance. The Taliban opposition in the country has come to include disaffected Durranis, Ghilzai, and factions of the Karlandri confederation (such as the Haqqani of the Zadran tribe, whose leader Jalaluddin was called “goodness personified” during the Soviet-Afghan War by Congressman Charlie Wilson,

10

and is today one of Al Qaeda’s principal allies).

When U.S.-backed forces first swept through Afghanistan, many of the remaining Taliban commanders fled for sanctuary to the Pashtun border regions of Pakistan. The Americans then began bombing these sanctuaries from the air and prodding the Pakistani army to make fitful incursions into tribal areas. The result was that hitherto unaligned Pakistani Pashtun began joining forces with the Afghan Taliban and Al Qaeda. This, in turn, has enabled Al Qaeda to survive, the Afghan Taliban to regroup and take the fight back into Afghanistan, and the Pakistani Taliban to emerge as a threat to Pakistan itself.

Pakistani Taliban are mostly enlisted from factions of the Mehsud, Wazir, and other Karlandri tribes. Before 2001, many of these tribal factions were largely unresponsive to the Afghan Taliban program to homogenize and integrate tribal custom, and suppress tribal independence under a single religious administration that claimed strict adherence to Sharia (in fact, a peculiarly Pashtun version of Sharia with a heavy dose of tribal custom). But the Pashtun border tribes became outraged at the Pakistani government for sending troops into the area and allowing Americans to bomb their homelands in an effort to kill off Al Qaeda and root out the Afghan Taliban. In Pakistan today, there’s no overarching Taliban organization that commands and controls the actions of its numerous tribal factions and unaffiliated adherents (often foot soldiers who fight for pay, status, and other rewards).

In the past, the Afghan Taliban tried to suppress tribal sentiments and the role of the qawms. Now, the New Taliban vie with the U.S.-backed coalition to enlist these sentiments to turn the qawms into militia. Both sides have grudgingly bowed to the fact that Pashtun politics is indeed truly local and that local politics must be mastered before grander schemes are tried. The problem is that the Taliban are better at this than we are.

A MATTER OF HONOR

A key factor helping the Taliban is the moral outrage of Pashtun tribes against those who deny them autonomy, including a right to bear arms to defend their tribal code, known as Pashtunwali. Its sacred tenets include protecting women’s purity

(namus),

the right to personal revenge

(badal),

the sanctity of the guest

(melmastia),

and sanctuary

(nanawateh).

Among all Pashtun tribes, inheritance, wealth, social prestige, and political status accrue through the father’s line.

Other books

Scraps & Chum by Ryan C. Thomas

Accidentally Still Married (The Naked Truth #2) by Carmen Falcone

o 0df2dc86c31d22a8 by Unknown

The Absolutist by John Boyne

Laura's Locket by Tima Maria Lacoba

Acceptance (Club X Book 5) by K.M. Scott

Harry Flashman and the Invasion of Iraq by H.C. Tayler

Stardust (The Starlight Trilogy #3) by Alexandra Richland

Marrying Up by Wendy Holden

THE THIEF OF KALIMAR (Graham Diamond's Arabian Nights Adventures) by Graham Diamond