Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists (65 page)

Read Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists Online

Authors: Scott Atran

As things now stand, I see a chance that political freedom and diversity will triumph, but also a chance that a brave new world of dumbing homogeneity and deadening control by consensus will prevail. Or perhaps they will alternate in increasingly destructive cycles. For the media-driven global political awakening is the oxygen that is both opening societies and spreading spectacular violence to close them.

As it happened, around the Shiite holiday of Ashura (December 28, 2009), I received an e-mail from a friend in Tehran who said how helpless he felt to stop the merciless beating of a young woman by government thugs, but he went on to say, “We will win this thing if the West does nothing but help us keep the lines of communication open with satellite Internet.” The same day, I saw the Facebook communications of “farouk 986,” the 2009 Christmas Day plane-bomb plotter who bound himself into a virtual community where dreams of glory awaken real and bloody sacrifice.

“Happiness is martyrdom” can be as emotionally contagious to a lost youth on the Internet as “Yes, we can.” That is a stunning and far-reaching development that we have not yet begun to master or steer.

EPILOGUE:

ABE’S ANSWER—THE QUESTION OF POLITICS

D

uring the American Civil War, Abraham Lincoln made a speech in which he referred sympathetically to the Southern rebels. An elderly lady, a staunch Unionist, upbraided him for speaking kindly of his enemies when he ought to be thinking of destroying them. His response was classic: “Why, madam,” Lincoln answered, “do I not destroy my enemies when I make them my friends?”

1

TETUÁN, MOROCCO, JUNE 2007

“What do you think is going on in Mezuak? Why do they want to be martyrs?” the

New York Times

reporter asked me about the young men in this neighborhood bound for glory and a grave in Iraq.

People often want an author to give a book in a sentence. What I told the

Times

reporter then will do fine for this one: “People, including terrorists, don’t simply die for a cause; they die for each other, especially their friends.”

2

In that light, I should have offered Lincoln’s wisdom at that White House meeting when the woman from Vice President Cheney’s office told me in the sternest tough-guy voice she could muster that the way to stop young people from choosing the path to radicalization is to bomb them in their lairs. (Never mind the impracticality of this, seeing as how the places I had talked to her about were in the middle of several large European and allied cities.)

Granted, Lincoln had little political “experience” beyond a single term in Congress fifteen years before being elected president. Still, his thought is for the ages. How, precisely, to make our enemies our friends is perhaps the most difficult political challenge of all—without having to fear or fabricate a common enemy to do it (as when Reagan mused to Gorbachev that a Martian invasion might finally bring humanity together).

THE WHITE HOUSE, FEBRUARY 2008

So I got another chance, back at the White House for a briefing to staff from the National Security Council and Homeland Security. I showed some charts and graphs on terror networks and gave my spiel about the need for field-based research to understand what’s happening in the communities that produce jihadis in order to offer young people a different path.

“I’m convinced,” one of the senior staffers said, “but …” He reached down for his BlackBerry and looked at the screen in mock surprise: “I don’t see any messages here in the last five minutes telling me that we have to move right away on field-based research,” he said, glancing up and around like a prairie dog with a conspiratorial smile.

The guy was smart. He was teaching me, in the quickest and most pointed way, how things work here.

“You’ll have a better chance with Congress on this, and we’ll see how we can help.”

He was right about Congress, where you can usually find some subcommittee willing to listen, and he was helpful. The problem, though, is that Congress hasn’t much say on anything to do with national security, or even foreign policy. Yes, Congress has long-term control over the budget, but most foreign-policy plans and decisions run on a short-term schedule that Congress usually only reacts to when things go way south. The White House sets practically the entire agenda, then gives the departments of Defense and State directives for realizing that agenda, including any related “human factors” research, which is usually a very distant and paltry afterthought. At the National Security Council, there’s no representation for health, education, labor, or most anything to do with social relationships and human welfare. Almost all who sit and advise are from defense, intelligence, and economic agencies. (The State Department’s Agency for International Development is an exception that only proves the rule.)

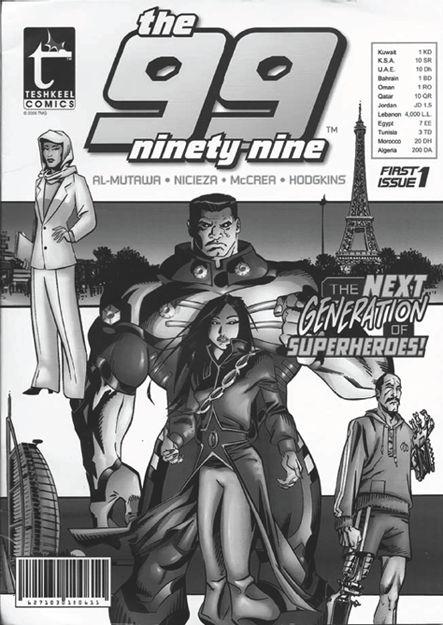

The 99—

anti-jihadi Muslim superhero comic books appeal to youth.

So I tried a glibber tack, though dead-serious at its core, to show that bombing doesn’t come close to delivering the kind of positive messages you can find in sport or with action heroes. There’s a commercial action-adventure series called

The 99,

in which young Muslim superheroes dodge bullets and bullies to aggressively “fight for peace,” with “multicultural initiatives” and “worldwide relief efforts,” as the first issue trumpets. (Started as a comic book in Arabic and English versions by Naif Al-Mutawa, a Columbia University graduate from Kuwait, in 2009 it was dubbed “one of the top 20 trends sweeping the globe” by

Forbes

magazine and is now moving into television and film.)

3

I put out my comic books on the large oval table, asked the people around it to look, and argued that adventure beats “moderation through education”—the second hackneyed cure for terrorism after bombing—any day in the world of the young, who yearn for adventure in life. Besides, the data show that most young people who join the jihad had a moderate and mostly secular education to begin with, rather than a radical religious one. And where in modern society do you find young people who hang on the words of older educators and “moderates”? Youth generally favors actions, not words, and challenge, not calm. That’s a big reason so many who are bored, underemployed, overqualified, and underwhelmed by hopes for the future turn on to jihad with their friends. Jihad is an egalitarian, equal-opportunity employer (well, at least for boys, but girls are Web-surfing into the act): fraternal, fast-breaking, thrilling, glorious, and cool. Anyone is welcome to try his hand at slicing off the head of Goliath with a paper cutter.

Now, I have no illusions that comic books will do the trick. In the United States and across the world, readership for comic books has declined by about an order of magnitude since my youth. And even more since my father’s time, when Superman’s motto of “Truth, Justice, and the American Way” was actually an important part of popular and civic culture. (In World War II, German soldiers would taunt Americans by yelling, “Fuck Superman!”) Television and especially blockbuster movies are the only real channels through which comic-book action heroes make it into the mainstream nowadays; and these newer mass commercial heroes, like the Terminator, are hardly good moral models for wayward youth.

I really like

The 99,

but my intention is not to push these particular comic-book heroes. What counts is the counter-radicalization strategy that the comics illustrate. A

Newsweek

article took up the point and put it more succinctly: “These kids dream of fighting for some meaningful cause that will make them heroes in their communities. No, ‘The

99’

comic books are not going to solve that problem. But … attracting young people away from jihadi cool … might even help convince Washington that ‘knowledge is the true base of power.’ “

4

When you look at young people like the ones who grew up to blow up trains in Madrid in 2004, carried out the slaughter on the London Underground in 2005, and hoped to blast airliners out of the sky en route to the United States in 2006 and 2009, when you look at whom they idolize, how they organize, what bonds them and what drives them, then you see that what inspires the most lethal terrorists in the world today is not so much the Koran or the teachings of religion as it is a thrilling cause and call to action that promises glory and esteem in the eyes of friends, and through friends, eternal respect and remembrance in the wider world that they will never live to enjoy.

Because the young, feeling immortal, do not fathom how short and fragile life and memory are—even remembrance of heroes—or how forever long are death and forgetfulness. They don’t understand that their deaths are staged so that stories will be broadcast, not about them—they are as nameless as their victims—but about the Cause.

If we can discredit their vicious idols (show how these bring murder and mayhem to their own people) and give these youth new heroes who speak to

their

hopes rather than just to ours, then we’ve got a much better shot at slowing the spread of jihad to the next generation than we do just with bullets and bombs. And if we can desensationalize terrorist actions, like suicide bombings, and reduce their fame (don’t help advertise them or broadcast our hysterical response, for publicity is the oxygen of terrorism), the thrill will die down. Then the terrorist agenda will likely extinguish itself altogether, doused by its own cold raw truth: It has no life to offer. This path to glory leads only to ashes and rot.

ERICE, SICILY, MAY 2008

Barack Obama seemed poised to wrap up the Democratic presidential nomination and I was at a gathering of the World Federation of Scientists Permanent Monitoring Panel on Terrorism. Pakistani Senator Khurshid Ahmad, an Islamic economist and leading intellectual of modern Islamic Revivalism, was speaking to Ramamurti Rajaraman, one of India’s great theoretical physicists and secular humanists. Said the senator, a self-proclaimed Muslim fundamentalist: “Obama is a ray of hope in an otherwise dismal situation for three reasons: His election would be a blow to racism around the world. He embodies the aspirations of a new generation inside and outside America, which looks towards him as a harbinger of change who may respect the feelings and wishes of people. And he has been outspoken on a number of issues, which at least shows that he is open to dialogue on issues that have been ignored by the present unilateral American leadership. But I fear America’s political class will keep him tied to bad policies in Pakistan and across Muslim lands.”

“Why does the United States get to choose Obama?” Rajaraman retorted, directing a mock scolding toward me. “We want him, the world needs him, and we all deserve him more than you do.”

“So you think he’s the Messiah?” I laughed.

“He is hope,” the Indian scientist was more serious now. “Hope is better than fear and despair. This War on Terror only increases the world’s despair.”

Good enough.

Fear may be the oldest and strongest emotion in our species. In forbidding forests, fear kept our forebears safe from predators, firing our hearts and brains at every uncertain shadow or noise. “Better safe than sorry” is a good survival strategy. Afraid for nothing, you still live; wrongly unafraid, you die.

But “in politics, what begins in fear usually ends in folly,” said the English philosopher-poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Still, the politics of fear is a classically effective sales con, like the vacuum-cleaner vendor who throws down dirt and convinces you how much you need his product to clean up the mess.

The politics of hope plays to a less primitive emotion. “Hope is a waking dream,” said Aristotle, of things that never were but could be. It is a yearning that the future will be different from what we can reasonably expect today, and that there is more to existence than what we see in the here and now. Religion and science are rooted in hope, whatever else their uses or abuses. So is political imagination: “Some men see things the way they are, and ask why?” mused Robert Kennedy. “I dream of things that never were, and ask why not?”

It is the hope that fear between peoples will lessen and that all will be freer to pursue happiness for their families and communities. Of course, many knew little about the junior senator from Illinois or even where or what Illinois was, but people—especially the young—projected their own hopes on him as well as hopes for humanity. They saw in him the face of diversity, a growing symbol that is already making it harder for Al Qaeda and associates to promote the demonization of America, which drives their viral movement. (For this alone, he may have deserved his Nobel Peace Prize).

5