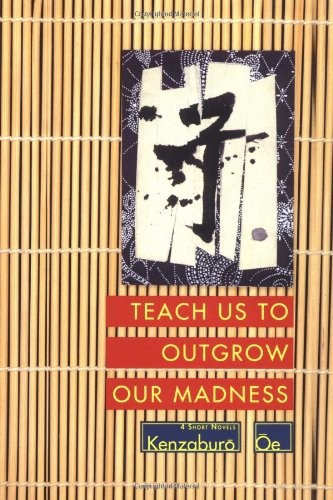

Teach Us to Outgrow Our Madness

Read Teach Us to Outgrow Our Madness Online

Authors: Kenzaburo Oe

TEACH US TO OUTGROW OUR MADNESS

Books by Kenzabur

ō

Ō

e Published by Grove Press

Somersault

Rouse Up O Young Men of the New Age!

A Personal Matter

The Crazy Iris and Other Stories

Hiroshima Notes

Nip the Buds, Shoot the Kids

A Quiet Life

Teach Us to Outgrow Our Madness

Four Short Novels by

KENZABURO

Ō

E

Translated and

with an Introduction by

John Nathan

Copyright © 1977 by John Nathan

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, or the facilitation thereof, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Any members of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or publishers who would like to obtain permission to include the work in an anthology, should send their inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003.

“Happy Days Are Here Again” copyright © 1929 WARNER BROS. INC.

Copyright renewed. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 76-54582

eBook ISBN-13: 978-0-8021-9543-2

Designed by Steven A. Baron

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

The Day He Himself Shall Wipe My Tears Away

Teach Us To Outgrow Our Madness

These translations are for Mayumi.

I met Kenzaburo

Ō

e (OH-way) in 1964, at Yukio Mishima’s Christmas Eve party. I was there because I was Mishima’s translator at the time.

Ō

e was there because Mishima had invited everyone who mattered that year, from boxers to drag queens, and because

Ō

e’s vanity and maybe his country-cousin curiosity had drawn him to the lights. I spotted him right away and I watched him with awe, for I had just discovered his novel

A Personal Matter

and thought it the most passionate and original and

funniest and saddest Japanese book I had ever read.

Ō

e was standing apart with his best friend in the world in those days, K

ō

b

ō

Abé, drinking steadily and looking uncomfortable. His appearance surprised me. Like everything he has written,

A Personal Matter

was a vibrant, headlong book powered by gorgeous energy. The author was an owlish, pudgy man in a baggy dark suit and a skinny tie; parked in the corner with his round face and sloping shoulders and soft belly, he looked absolutely meek, a Japanese badger. Then something astonishing happened.

Ō

e drained his glass and handed it to Abé to hold, shuffled across the room to where Mishima’s wife, Yoko, was arranging dishes on her buffet table, and said clearly, in English, “Mrs. Yoko, you are a cunt!” I never knew whether Yoko understood him, but she cannot have missed the sudden fierceness in his manner, for she produced a stricken smile and moved away. Leaving me and

Ō

e more or less alone together. I looked over at him and he shrugged and threw up his hands, as if to say “Well she

is,

what can you do!” “Where did you learn English like that?” I asked in Japanese. “Ah,” he said, and now there was real excitement in his eye and he stepped closer, “the hero of Norman Mailer’s ‘The Time of Her Time’ speaks the very same line.”

Before the party was over,

Ō

e had asked me to teach him “English conversation.” He had been invited to an international writers’ seminar Professor Henry Kissinger was organizing at Harvard, and he was bound to go so that he could deliver a speech about the survivors of Hiroshima. Naturally, I agreed. And so for three months

Ō

e came to my house several mornings a week, and we spoke in English about books he chose. We began with a volume of Baldwin essays, and went on to

Advertisements for Myself,

The Adventures of Augie March,

and

Sexus.

Ō

e had a large vocabulary and an uncanny gift for comprehending English meaning above and below the surface. But he had never spoken the English words he understood so very well and could not pronounce them intelligibly. I don’t think I helped him much; to this day, his spoken English is no great pleasure to the native ear. But

Ō

e taught me a lot about how to read in my own language. He could even do poetry! His favorite poet at the time was W.H. Auden, and I swear he took me deeper into Auden’s world than any teacher I ever had at school. Sometimes I felt threatened by his superior reach and tried to confront him with things he didn’t know. Once I sprang

Rabbit, Run

on him, having just read the book, and he asked me if I had seen Updike’s poems about basketball in

The New Yorker.

I had not, so he brought them to our next session and we read them together.

When it came time for

Ō

e to leave for Harvard I saw him off at the airport. He was distraught. When he had passed through Customs and entered the fishbowl waiting room from which there is no turning back, he rushed to the plate glass window separating us and scribbled a line in a notebook and held it up for me to read: “John, how very happy you are not to have to go!” It wasn’t just that he was leaving home: in 1960 he had been the youngest Japanese in an official mission sent to Peking to meet with Chairman Mao and Chou En-lai; the following year he had traveled in Europe and had interviewed another of his heroes, Jean-Paul Sartre. But this time was different. Now he was leaving for AMERICA, a land of exquisite terror and irresistible pull which had burned at the center of his imagination since he was a boy.

Ō

e’s first actual encounter with America was in the

fall of 1945, when the Occupation jeeps drove into the mountain village where he lived. Like everyone else in the village, he expected the Americans to begin by raping the women and castrating the men. Then the jeeps arrived and what really happened was unimaginable. Instead of destruction, the GI’s rained Hershey bars and chewing gum and canned asparagus down upon the village, and the children scrambled for the sweets,

Ō

e with them. Relief is what he felt, and gratitude and anger and humiliation, and those potent feelings have remained entangled in him and, as he has said himself, defy his efforts to sort them out.

Ō

e was ten years old at the time. His second decisive encounter with America occurred four or five years later, when he read for the first time a Japanese translation of

Huckleberry Finn.

It seems unlikely that a Japanese schoolboy knowing only the tiny, manageable wilderness of the Japanese countryside could be much moved by Huckleberry’s pilgrimage down the vast Mississippi:

Ō

e was ardently moved. It was Huck’s moral courage, literally Hell-bent, that ignited his imagination. For

Ō

e the single most important moment in the book was always Huck’s agonized decision not to send Miss Watson a note informing her of Jim’s whereabouts and to go instead to Hell. With that fearsome resolution to turn his back on his times, his society, and even his god, Huckleberry Finn became the model for

Ō

e’s existential hero. As he read on in American fiction,

Ō

e found inspiration in other American writers, Philip Roth, Saul Bellow, Kerouac and Henry Miller and, particularly, Norman Mailer. But the basis of his admiration for these writers was his perception of their heroes—of Portnoy and Holden Caulfield and Dean Moriarty and Augie March and all the transformations of the

Mailer prototype from Sergius O’Shaugnessy in

Deer Park

and the bullfighter in “The Time of Her Time” to Mailer himself in

Armies of the Night—as

modern incarnations of

Huckleberry Finn.

The heroes in American fiction that matter to

Ō

e are, invariably, sickened by their experience of “civilization,” driven on a quest for salvation in the form of personal freedom beyond the borders of safety and acceptance. Brothers to

Huckleberry Finn,

they are men who have no choice but to “light out for the territory.”

Ō

e’s own outrage, not so much at the American invaders as against his own kind, helps explain his affinity for the outraged heroes in American writing. On August 15, 1945, Emperor Hirohito went on the radio to announce the Surrender, and deprived

Ō

e of his innocence. Until that day, like all Japanese schoolchildren, he had been taught to fear the Emperor as a living god. Once a day his turn had come to be called to the front of the classroom and asked, “What would you do if the Emperor commanded you to die?” and

Ō

e had replied, knees shaking, “I would die, Sir, I would cut open my belly and die.” In bed at night, he had suffered the secret guilt of knowing, at least suspecting, he was not truly eager to destroy himself for the Emperor. Sick with a fever, he had beheld the Emperor in a terrifying nightly dream, soaring across the sky like a giant bird with white feathers. Then Hirohito went on the air and spoke in the voice of a mortal man.

The adults sat around their radios and cried. The children gathered outside in the dusty road and whispered their bewilderment. We were most surprised and disappointed by the fact that the Emperor had spoken in a

human

voice. One

of my friends could even imitate it cleverly. We surrounded him, a twelve-year-old in grimy shorts who spoke in the Emperor’s voice, and laughed. Our laughter echoed in the summer morning stillness and disappeared into the clear, high sky. An instant later, anxiety tumbled out of the heavens and seized us impious children. We looked at one another in silence. … How could we believe that an august presence of such awful power had become an ordinary human being on a designated summer day?

(A Portrait of the Postwar Generation.)

In a single day, all the truth

Ō

e had ever learned was declared lies. He was angry and he was humiliated, at himself for having believed and suffered, and at the adults who had betrayed him. His anger resided; it was the source of the energy he first tapped when he became a writer.

In 1954,

Ō

e was admitted to Tokyo University and left the island of Shikoku for the first time to go up to the big city. He enrolled in the department of French literature, the course for serious students at Tokyo, where it was held that American writing was inferior, and became absorbed in Pascal and Camus and Sartre, who was to be the subject of his graduation thesis. He was a brilliant student but he kept to himself; he was withdrawn by nature, always a loner, and because he was ashamed of his provincial accent, he stuttered. He lived in a rooming house near the campus, and it was there at night, swallowing tranquilizers with whisky, that he began to write the stories which established him in half a year as the spokesman for an entire generation of young Japanese whose distress he identified. His first published story, “An Odd Job,” appeared in the May, 1957 issue of the

University literary magazine. It was about a bewildered college student who takes a part-time job slaughtering dogs to be used in laboratory experiments.

There was almost every breed of dog, yet somehow they looked alike. I wondered what it was. All mongrels, and all skin and bones? Or was it the way they stood there leashed to stakes, their hostility quite lost? That must have been it. And who could say the same thing wouldn’t happen to us? Helplessly leashed together, looking alike, hostility lost and individuality with it—us ambiguous Japanese students. But I wasn’t much interested in politics. I wasn’t much interested in anything. I was too young and too old to be involved in anything. I was twenty; it was an odd age, and I was tired. I quickly lost interest in that pack of dogs, too.…