Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh (86 page)

Read Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh Online

Authors: John Lahr

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Literary

A House Not Meant to Stand

is a funhouse of mirrors in which comic images of Williams’s humiliated past distort his fury and reflect back his pain as pleasure. Williams’s ornery, bombastic father, CC, returns, under his own name, as the comic menace, Cornelius. Although he has acquired new illnesses (osteoarthritis, pancreatitis) and new pills (Cotazym, Donnatal) from his author, his overstuffed chair and his brutish detachment from his family are very much his own. “I don’t respect tears in a man, and over-attachment to Mom, Mom, Mom,” Cornelius tells his feckless, second son, Charlie. In the play, as in Williams’s life, Cornelius’s hectoring has already driven two children out of the house: Chips, the gay and now dead first son, and Joanie, the daughter, the unseen resident of a lunatic asylum. CC referred to the young Williams as “Miss Nancy.” Cornelius similarly taunts Chips’s effeminacy—“I remember when he was voted the prettiest girl at Pascagoula High.” At the opening, returning from Chips’s funeral, Cornelius and Bella try to understand their son’s tragic early death; Cornelius puts Chips’s homosexuality down to Bella’s cosseting:

is a funhouse of mirrors in which comic images of Williams’s humiliated past distort his fury and reflect back his pain as pleasure. Williams’s ornery, bombastic father, CC, returns, under his own name, as the comic menace, Cornelius. Although he has acquired new illnesses (osteoarthritis, pancreatitis) and new pills (Cotazym, Donnatal) from his author, his overstuffed chair and his brutish detachment from his family are very much his own. “I don’t respect tears in a man, and over-attachment to Mom, Mom, Mom,” Cornelius tells his feckless, second son, Charlie. In the play, as in Williams’s life, Cornelius’s hectoring has already driven two children out of the house: Chips, the gay and now dead first son, and Joanie, the daughter, the unseen resident of a lunatic asylum. CC referred to the young Williams as “Miss Nancy.” Cornelius similarly taunts Chips’s effeminacy—“I remember when he was voted the prettiest girl at Pascagoula High.” At the opening, returning from Chips’s funeral, Cornelius and Bella try to understand their son’s tragic early death; Cornelius puts Chips’s homosexuality down to Bella’s cosseting:

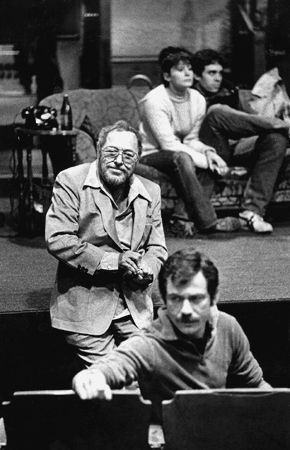

In rehearsal for his last full-length play,

A House Not Meant to Stand

, 1981

A House Not Meant to Stand

, 1981

CORNELIUS: You encouraged it, Bella. Encouraged him to design girls’ dresses. He put a yellow wig on and modelled ’em himself. Something—

drag

they call it. Misunderstood correctly—by the neighbors.

BELLA: He could of grown outa that.

CC threatened to kick Edwina and her children out of the family home; in

A House Not Meant to Stand

, Cornelius threatens to commit Bella to a mental home in order to get his hands on her “moonshine money,” the cash he thinks his wife has inherited from her bootlegging grandfather and stashed away. (She has.) In a plot point that Williams adapted from his own brother’s folly, Cornelius decides to make a run for Congress and wants the money from Bella to pay for his campaign—the very skulduggery that Williams feared Dakin had become involved in when newspapers reported that Edwina had made a fifty-thousand-dollar contribution to his ill-fated Illinois senatorial bid. (“No one whom I have discussed the question with has any doubt that he will be defeated in this race,” Williams wrote to his mother in 1972. “Please assure me that you have not thrown so much money away on such a hopeless cause.”) Williams wickedly transforms the incident into the driving force of his comedy: Will Cornelius get his hands on the “Dancie money”? Will the confused Bella manage to hang on to it?

A House Not Meant to Stand

, Cornelius threatens to commit Bella to a mental home in order to get his hands on her “moonshine money,” the cash he thinks his wife has inherited from her bootlegging grandfather and stashed away. (She has.) In a plot point that Williams adapted from his own brother’s folly, Cornelius decides to make a run for Congress and wants the money from Bella to pay for his campaign—the very skulduggery that Williams feared Dakin had become involved in when newspapers reported that Edwina had made a fifty-thousand-dollar contribution to his ill-fated Illinois senatorial bid. (“No one whom I have discussed the question with has any doubt that he will be defeated in this race,” Williams wrote to his mother in 1972. “Please assure me that you have not thrown so much money away on such a hopeless cause.”) Williams wickedly transforms the incident into the driving force of his comedy: Will Cornelius get his hands on the “Dancie money”? Will the confused Bella manage to hang on to it?

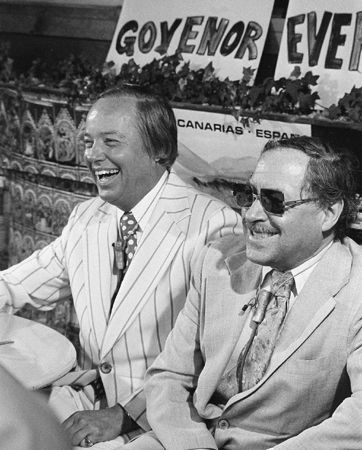

Helping brother Dakin Williams run for governor of Illinois, 1978

But the real autobiographical revelation of the play is the psychic atmosphere beneath it. Bella’s confounding maternal non-communication is a re-creation of the emotional absenteeism in Edwina that triggered her son’s compulsion to be seen, to turn his inner life into unforgettable event. Cornelius tells Charlie that “lunacy runs rampant” in his wife’s family, the neurasthenic “Dancies” (a variation on “the Dakins”)—just as CC used to berate Edwina’s ancestral line, which was filled with “alarming incidences of mental and nervous breakdowns.” Moving heavily around the house, confused and demented by grief at the loss of her eldest child, Bella is a sort of saintly sleepwalker, whose mind is always elsewhere:

CHARLIE: Mom?

BELLA:—Chips?

CHARLIE: No, no, Mom, I’m Charlie.

“Bella should be presented as a grotesque but heart-breaking Pieta,” Williams wrote in his notes. “She all but senselessly broods over the play as an abstraction of human love and compassion—and tragedy.” Retreating into herself, projected backward into the past and never alive to her present, she is haunted, and haunting. “My eyes keep clouding over with—time,” she says at one point. When she pokes around the kitchen, Charlie asks her what she’s looking for. “Life, all the life we had here!” she says. Bella pines for her children as they once were; she can’t think of them as adults. Bella is shown as a dutiful wife and mother. Unbidden she serves up an omelette to her son; she insists on doing the shopping; she responds without complaint to her husband’s imperious commands:

CORNELIUS: (

half-rising and freezing in position

) TYLENOL THREE. TYLENOL THREE!

(

Automatically

Bella crosses to him and removes the medication from his jacket pocket.

)

CORNELIUS: Beer to wash it down with.

BELLA: Beer . . .

(

She shuffles ponderously off by the dining room

.)

Her actions appear nurturing; her aggression—her refusal to take in her children—is harder to see. At one point, Bella admits to her neighbor, Jessie, that “Little Joanie” is in the state lunatic asylum. “How did this happen to Joanie?” Jessie asks. “I don’t know,” Bella says. Joanie has sent a letter. Bella’s first instinct is not to face it, to have Jessie read it for her. In the end, Bella reads it aloud, an exercise that demonstrates to the audience, if not to Bella, that hearing is not understanding: “All I had was a little nervous break down after that sonovabitch I lived with in Jefferson Parish quit me and went back to his fucking wife.” Bella stops to apologize, and offers her only insight: “She seems to have picked up some very bad langwidge somehow.” A hilarious, subtle piece of invention, the letter is a testament to the family’s climate of denial. Bella can’t fathom the landscape of impoverishment that Joanie’s language betrays. She has loved her children but has not connected to them. She frets about them, but she has never known them or understood her own contribution to their haplessness.

As Bella approaches her end, in a reversal of the trope of

The Glass Menagerie

, where, in an exhibition of his literary aplomb, Tom at the finale silences the ghosts of his past (“Blow out your candles, Laura—and so good-bye”), Bella now summons up her own specters. According to the stage directions, “Ghostly outcries of children fade in—in Bella’s memory—projected over house speakers with music under. She moves with slow, stately dignity.” The children’s voices bring with them the “enchanting lost lyricism of childhood”:

The Glass Menagerie

, where, in an exhibition of his literary aplomb, Tom at the finale silences the ghosts of his past (“Blow out your candles, Laura—and so good-bye”), Bella now summons up her own specters. According to the stage directions, “Ghostly outcries of children fade in—in Bella’s memory—projected over house speakers with music under. She moves with slow, stately dignity.” The children’s voices bring with them the “enchanting lost lyricism of childhood”:

VOICE OF YOUNG CHIPS:—

Dark

!

VOICE OF YOUNG CHARLIE:

Mommy

!

VOICE OF YOUNG JOANIE: We’re

Hungry

!

At the moment that Bella delivers the Dancie money into safe hands, the ghosts of her children gather around the kitchen table. “Chips—will you say—Grace,” she says. The line echoes Amanda’s first words in

The Glass Menagerie

: “We can’t say grace until you come to the table!” Amanda’s prayer for grace is answered, at the finale, by Tom’s empowered survival. In Williams’s final full-length play, thirty-seven years later, however, grace is only a memory. “Ceremonially the ghost children rise from the table and slip soundlessly into the dark,” the stage directions say. At the last beat, each ghost turns at the kitchen door “to glance back at their mother. A phrase of music is heard.” The ghosts’ departure brings the curtain down on Bella’s struggle; it also hints at Williams’s sense of an ending: a farewell to lyricism and to the spectral absences that have tormented and inspired him since childhood. With their stately exit, Williams seemed to imply, consciously or not, that he had said all he had to say.

The Glass Menagerie

: “We can’t say grace until you come to the table!” Amanda’s prayer for grace is answered, at the finale, by Tom’s empowered survival. In Williams’s final full-length play, thirty-seven years later, however, grace is only a memory. “Ceremonially the ghost children rise from the table and slip soundlessly into the dark,” the stage directions say. At the last beat, each ghost turns at the kitchen door “to glance back at their mother. A phrase of music is heard.” The ghosts’ departure brings the curtain down on Bella’s struggle; it also hints at Williams’s sense of an ending: a farewell to lyricism and to the spectral absences that have tormented and inspired him since childhood. With their stately exit, Williams seemed to imply, consciously or not, that he had said all he had to say.

“WHEN I HEAR [the critics] say that I have not written an artistically successful work for the theatre since ‘Night of the Iguana’ in 1961 they are being openly, absurdly mistaken,” Williams wrote in 1981.

A House Not Meant to Stand

was proof that Williams was right. The play, which ran for only a month at the Goodman, received generally positive local press, but the

New York

Times

didn’t bother to send a critic to review it. When it played for a week at the New World Festival of the Arts,

Time

mentioned it as “the best thing Williams has written since ‘Small Craft Warnings.’ ” In terms of narrative scope and theatrical daring, it was far better. Nonetheless, although he didn’t stop writing, for all intents and purposes Williams’s legend as a playwright ended in Chicago, where it had begun.

A House Not Meant to Stand

was proof that Williams was right. The play, which ran for only a month at the Goodman, received generally positive local press, but the

New York

Times

didn’t bother to send a critic to review it. When it played for a week at the New World Festival of the Arts,

Time

mentioned it as “the best thing Williams has written since ‘Small Craft Warnings.’ ” In terms of narrative scope and theatrical daring, it was far better. Nonetheless, although he didn’t stop writing, for all intents and purposes Williams’s legend as a playwright ended in Chicago, where it had begun.

Still, if the world was uninterested in Williams’s new work, it continued to honor the old. Williams turned seventy in 1981, on the heels of receiving the Common Wealth Award of Distinguished Service in Dramatic Arts, a twenty-two-thousand-dollar prize that he split with Harold Pinter. In June 1982, Harvard University, to which he had willed a large cache of his papers, after much badgering from St. Just, gave him an honorary degree. Open-collared and in a sports jacket amid the sea of crimson-gowned academics, Williams was ushered into Massachusetts Hall before the procession, where he mingled uncomfortably with the scholastic scrum and signed the guest book with the other honorands. Looking around the room, he noticed two nuns sitting on a sofa saying their rosaries, ignored by the milling crowd. “My God, that’s Mother Teresa,” he whispered to Robert Kiely, then master of Adams House, who was his escort. “In the strangest introduction I have ever made, I said respectfully to the tiny wrinkled nun, ‘Mother Teresa, this is Tennessee Williams,’ ” Kiely recalled, adding, “She looked up kindly, obviously having no idea who Tennessee Williams was.” Williams fell to his knees and put his head in her lap. Mother Teresa patted his head and blessed him.

While the parade of honors rolled on, there were signs that Williams was readying himself to leave it. That September, back in Florida, sitting alone in a bus-stop café, he struck up a conversation with a young novelist, Steven Kunes, and his wife. Charmed by their enthusiasm, he invited them back to his house. Williams asked Kunes about his novel-in-progress; after a while, he got up from the table, where they were having coffee, and returned with a large black case. He asked Kunes to look inside. “It was an Underwood typewriter from the nineteen-forties,” Kunes said. “ ‘I write very rarely on this anymore,’ he said. ‘But I used it for “Summer and Smoke” and “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.” It needs a new ribbon, and perhaps some oil. I didn’t know I’d be finding a place for it so soon. Write a play, Steven. Just write a play.’ ” In November, in his last public appearance, at the Ninety-Second Street Y in New York, Williams told the audience that he’d almost forgotten to show up. “He looked old,” John Uecker, a theater director and Williams’s caretaker at the time, recalled. “I knew that mortality had entered the picture.” Williams read for half an hour, then abruptly stood up. “That’s the end of the performance,” he said.

“I don’t understand my life, past or present, nor do I understand life itself,” he had written to his Key West friend Kate Moldawer that May. “Death seems more comprehensible to me.” On Christmas Eve, worried that their persistent telephone calls to Williams had gone unanswered, Moldawer and Gary Tucker, the director who had mounted the early versions of

A House Not Meant to Stand

, went to Williams’s house. He had locked himself inside three days earlier. The door had to be broken down. They found Williams on the floor, wrapped in a sheet, with pill vials and wine bottles around him. He was dehydrated, frail, and incoherent. He was rushed to a hospital, where, under a false name, he spent several days recovering. His Key West doctor told him that he could not continue much longer without prolonged hospitalization. “He just wouldn’t have it,” Uecker said. “You couldn’t tell him anything. He would only do what

he

wanted to do.”

A House Not Meant to Stand

, went to Williams’s house. He had locked himself inside three days earlier. The door had to be broken down. They found Williams on the floor, wrapped in a sheet, with pill vials and wine bottles around him. He was dehydrated, frail, and incoherent. He was rushed to a hospital, where, under a false name, he spent several days recovering. His Key West doctor told him that he could not continue much longer without prolonged hospitalization. “He just wouldn’t have it,” Uecker said. “You couldn’t tell him anything. He would only do what

he

wanted to do.”

Since the spring, Williams had toyed with the idea of renting out his Key West property. After his collapse, he finally decided to sell it. Sometime in the last days of December, Leoncia McGee, his housekeeper, overheard Williams calling for a taxi. When she inquired about the car, he told her that he was going to New York. She asked when he’d be coming back. “I won’t ever be coming home again,” he said. He handed her a check for her weekly salary and explained that she’d be receiving her future checks from New York. “Before Mr. Tom went away from the house alone, he came back into the kitchen and handed me another check, one for a thousand dollars,” McGee said. “ ‘What’s this for?’ I asked Mr. Tom. ‘For Christmas,’ he said. I walked with him to the front door, and before he left he kissed me on the cheek, a thing he never done before. That’s when I knew he wasn’t coming back. He kissed me, and he was travelling alone, and he never done them things before.”

Other books

Naked Sushi by Bacarr, Jina

An Eye for Murder by Libby Fischer Hellmann

Burn (Dragon Souls) by Fletcher, Penelope

The Wedding Wager (McMaster the Disaster) by Astor, Rachel

Time and Space by Pandora Pine

The Fearless by Emma Pass

Every Last Breath by Gaffney, Jessica

The Wrong Hostage by Elizabeth Lowell

The Unwritten Rule by Elizabeth Scott

Men Without Women by Ernest Hemingway