The $100 Startup: Reinvent the Way You Make a Living, Do What You Love, and Create a New Future (26 page)

Authors: Chris Guillebeau

Principle 3: Get Paid More Than Once

The final strategy for making sure your business gets off to a good start is to ensure that your payday doesn’t come along only once—you’d much rather have repeated paydays, from the same customers, over and over on a reliable basis. You may have heard of the terms

continuity program, membership site

, and

subscriptions

. They all mean roughly the same thing: getting paid over and over by the same customers, usually for ongoing access to a service or regular delivery of a product.

Back when people read newspapers (actual paper ones), they would subscribe to have them delivered to their doorstep or office. These days, iTunes and Netflix offer subscriptions to your favorite TV show or a regular series of movies. The utility company has a recurring billing program; every month you pay it for the ability to turn the lights on and heat your water. For decades, the Book of the Month Club (in various forms) has delivered new books to its members on a recurring basis.

Almost any business can create a

continuity program

. Speaking of book clubs, there is also a Pickle of the Month Club, an Olive Oil of the Month Club, and a Dog Treat of the Month Club. In Portland, my friend Jessie operates a Cupcake of the Month club. If you like bonsai plants but aren’t able to keep them alive very long, the Bonsai of the Month Club is for you, but you’ll have to choose among four competing companies that offer different versions.

§

Why is getting paid over and over such a big deal? First, because it can bring in a lot of money, and second, because it’s reliable income that isn’t dependent on external factors. Let’s run some quick numbers, assuming you offer a subscription service for $20 a month:

100 subscribers at $20 = monthly revenue of $2,000

or

yearly revenue of $24,000

1,000 subscribers at $20 = monthly revenue of $20,000

or

yearly revenue of $240,000

You can tweak either the number of subscribers or the price of the recurring service to see dramatic improvements. For example, adding 50 more subscribers generates $1,000 more per month, or $12,000 more per year. Raising the price to $25 a month with a subscriber base of 1,000 generates $5,000 more per month, or $60,000 more per year. Adjusting

both

options—attracting more subscribers and raising the price—generates an even greater increase.

(Note: Don’t get too hung up on the exact numbers here. The point is that in almost every case, a recurring billing model will produce much more income over time than will a single-sale model.)

Even better, after you attract customers to a recurring model

(and ensure that you keep them very happy), they are much more likely to purchase other things from you. Brian Clark is an expert at continuity programs, having created a true empire from the art of moving customers from one-time purchases into recurring subscriptions. Here’s what he has to say about this process:

Our general model is to offer a varied line of complementary products and services. Some are one-time purchases that begin the customer’s relationship with us, and others are software and hosting services that involve recurring monthly or quarterly billing. While we strive to build all our product lines, the general strategy is to move as many one-time purchase customers as possible to a more lucrative recurring service.

For example, our StudioPress division sells WordPress themes (designs) to online publishers and has over 50,000 customers. These are one-time purchases, although many people end up coming back to purchase additional design options. We also provide ongoing support to all of these customers.

Over time, we offer our Scribe SEO service or our new WordPress hosting service to our StudioPress customers, which transfers the nature of the relationship into one that is much more economically beneficial for us. But the secret ingredient to this migration is the trust we’ve developed with those customers from the initial one-time purchase. We treat people well, period. This means before an initial sale is made with our free content, and even better once they become a customer, no matter the size of the purchase.

The key to this model is not market share. It’s

share of the customer

. And to gain more of each customer’s budget, you first have to zealously treat every customer as a “best” customer,

no matter which ones actually end up becoming the proverbial “customer for life.”

The most important thing Brian says here is in the last paragraph: “It’s not market share; it’s share of the customer.” Like many of the people in this book, Brian doesn’t spend much time worrying about what other people are doing—he worries about improving his customers’ lives through helpful services. As a result, he gets paid over and over again.

Getting paid more than once is great, but be aware of a couple of concerns. First, many consumers are wary of subscriptions, because they worry that they’ll keep getting billed for the service after they stop using it or that it will be a big hassle to cancel. (To deal with the second problem, I created a “no pain in the ass” cancellation button for my site.) To encourage broad waves of initial sign-ups, many programs offer free or low-cost trials to get new prospects in the door. This works, but there is often a huge dropout rate after the trial ends. Just be aware of this, and make sure you continue to provide value as long as people are paying.

The $35,000 Experiment

One day I received an intriguing message from one of my customers, who successfully built a new business over the past year and is now making an average of $4,000 to $5,000 a month from his industry. In the email he told me about the results from an interesting experiment. I asked if I could share the results with other customers (and eventually put it in this book), but he was concerned about his competition learning how easy it was to increase profits. He finally said I could share

this information as long as I didn’t unmask him. Here’s his follow-up note to me with the details:

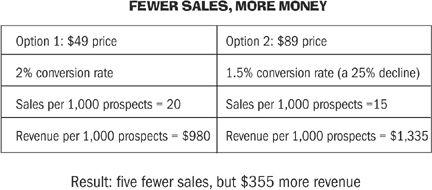

As mentioned yesterday, I wanted to check something in my product. I set up an experiment that only tested a single variable: price. On one sales page I had $49, and on another $89. Nothing was different at all—same copywriting, same order process, same fulfillment. To be honest, I thought that $49 was a better price, but I had set that price somewhat arbitrarily. Guess what? Conversion went down … slightly. But overall income actually increased! This is what really surprised me. I discovered that I could sell less but actually make more money due to the higher price.

I then decided to test it at $99. Why not, right? But from $89 to $99 I saw a bit more of a drop-off, and I got worried. I’m now back at $89, and even with the lower conversion factored in, I worked out that I’ve given myself a $24 raise on every product that sells. These days we are selling at least four copies a day. If everything else remains consistent, I’ll make $35,040 more this year … all from one test.

I’ve decided to do some more tests. :)

Isn’t that interesting? Here’s how the numbers break down in this example:

Note that if the conversion rate dropped further, say, to 1 percent instead of 1.5 percent, the price change would not be a good idea. But in some cases, the news is actually better than it is in this example: When you raise the price, you don’t always see a drop in the conversion rate. If you successfully raise prices without lowering the conversion rate, it’s time to order the champagne.

The point is that experimenting with price is one of the easiest ways to create higher profits (and sustainability) in a business. If you’re not sure what price to use for something, try a higher one without changing anything else and see what happens. You might find yourself with an extra $24 per sale—maybe more.

After I met Naomi Dunford in England, I saw her again a year later in Austin, Texas, where we were both in town for the South by Southwest (SXSW) Interactive Festival. Earlier that day, she had run into a money problem. The problem wasn’t a

lack

of money; her business was doing extremely well, on the way to breaking the $1 million a year barrier. The problem was

access

to money. Because Naomi is Canadian but has lived in the United States, the United Kingdom, and elsewhere, she often has issues with her PayPal account being closed as she travels the world, leaving her with plenty of funds in the account but no way to access them. In this case, she needed $900 to register for a conference that had just been announced … and would sell out quickly. What to do?

Naomi realized that although she didn’t have $900 with her, she probably knew someone in Austin willing to loan her the use of a credit card so she could register. Asking around, she found three

volunteers in the first two minutes who all said, “Sure, no problem. Here’s my card.”

As we talked about it further, we realized that most of us have access to all kinds of financial and social capital that we don’t usually think about but could call upon easily if necessary. If one guy hadn’t lent her his credit card, someone else would have. The trick was that she had to be willing to think creatively. If she had just said, “Oh, I guess I can’t register now,” she would have missed out. Being able to think of different means to achieve her goal led Naomi out of the homeless shelter a decade ago and to the highly successful IttyBiz. “Right before starting,” she said, “I was taking the bus to work, making 55 percent of a $30,000 income. My phone was cut off from lack of payment. Now I employ six people and help hundreds of others become self-employed.”

We all have more than we think. Let’s put it to good use.

KEY POINTS

There’s nothing wrong with having a hobby, but if you’re operating a business, the primary goal is to make money.

Going into debt to start a business is completely optional. Every day, people open and operate successful ventures without any kind of outside investment or borrowing.

The average business can improve its odds of success greatly by getting paid in more than one way and at more than one time. You can do this with a variety of methods. (We’ll cover this much more in

Chapter 11

.)

Whether it’s money, access to help, or anything else, you probably have more than you think. How can you get creative about finding what you need?