The $100 Startup: Reinvent the Way You Make a Living, Do What You Love, and Create a New Future (25 page)

Authors: Chris Guillebeau

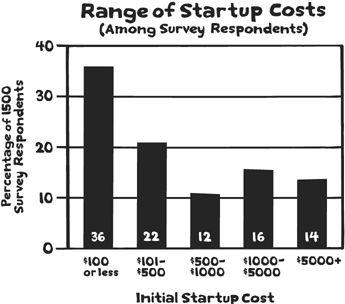

These stories are not outliers. When I began the research for this book, I received more than 1,500 nominations, with similar stories from all over the world. You can see the range of startup costs from our study group in the graph below. The average cost of the initial investment was $610.60.

*

You might expect that certain types of businesses are easier to start with limited funds, and that is correct. It’s also the whole point: Since it’s so much easier to start a microbusiness, why do something different unless or until you know what you’re doing? Small is beautiful, and all things considered, small is often better.

Unconventional Fundraising from Kickstarter to Car Loans

What if you’ve thought it through and you do need to raise money somehow? Whenever possible, the best option is your own savings. You’ll be highly invested in the success of the project, and you won’t be in debt to anyone else. But if this isn’t possible, you can also consider “crowdraising” funds for your project through a service such as

Kickstarter.com

. Shannon Okey did this with a project to boost her craft publishing business. She asked for $5,000 and received $12,480 in twenty days thanks to a nice video and well-written copy.

Before going to the masses, Shannon went to her bank for a small loan. Her business was profitable and promising, with several new publications coming out over the next year. This wasn’t just any bank. It was a community bank in Ohio where she had an excellent personal and business relationship. Shannon was a meticulous bookkeeper with a conservative attitude toward finances; she brought along detailed sales figures and a clear plan to repay the money. Unfortunately, when she mentioned “craft publishing,” she was dead in the water. “They looked at me like I was a silly, silly woman who couldn’t possibly know anything about running a business,” she said.

The rejection turned into an opportunity. Taking the project on Kickstarter generated both funds

and

widespread interest in the project. Nearly three hundred backers came through with donations ranging from $10 to $500, leaving the project fully funded with capital to spare. Oh, and Shannon was not one for going quietly.

After she reached the $10,000 level in her Kickstarter campaign, she printed out the front page of the site, wrapped the page around a lollipop, and sent it off to the bank’s underwriters. “I think they got the message,” she says.

As I collected stories for the book, I was mostly interested in people who avoided debt completely. But I did hear two fun stories about borrowing money that I thought were worth sharing. On a flight from Hong Kong to London, Emma Reynolds and her future business partner Bruce Morton had an idea for a consultancy that would work with big companies to improve their staffing and resourcing. They calculated that they would need at least $17,000 to start the new firm. There was just one problem … or actually, two: Emma was twenty-three and unlikely to get a business loan, and Bruce was going through a divorce and would also be a poor candidate for a business loan. Somewhere during the twelve-hour flight, one of them realized that although they couldn’t get a business loan, they could probably get a car loan.

Bruce proceeded to do just that, borrowing $17,000 for a car and then investing the funds in the business with Emma instead. They paid back the car loan within ten months, and the bank never found out that there was no actual car. Now the firm employs twenty people, is highly profitable, and has multiple offices in four countries.

†

Finally, here’s a fun story from Kristin McNamara, who started a California gym specializing in climbing:

To fund the latest incarnation of the gym, we called upon the community to “invest” in us, much like a three-year CD. We

offered 3 percent above prime, which is more than you could get then or now, and people I’ve never even seen at the facility came up with the cash to get it started. My partner and I, the founders, are the only paid full-time staff, and we just hired someone to manage the volunteers for us for a small stipend. Our community fundraising project brought in $80,000.

As these lessons in improvisation show, if you need to raise money, there’s more than one way to do it.

(Three Key Principles to Focus on Profit)

As we’ve seen, it’s usually much more important to focus your efforts on making money as soon as possible than on borrowing startup capital. In different ways, many of our case studies focused on three key principles that helped them become profitable (either profitable in the first place or more profitable as the business grew). I’ve noticed that the same thing holds true in my businesses. The more I focus on these things, the better off I am. In short, they are as follows:

1. Price your product or service in relation to the benefit it provides, not the cost of producing it.

2. Offer customers a limited range of prices.

3. Get paid more than once for the same thing.

We’ll look at each of them below.

Principle 1: Base Prices on Benefits, Not Costs

In

Chapter 2

, we looked at benefits versus features. Remember that a feature is descriptive (“These clothes fit well and look nice”) and

a benefit is the value someone receives from the item in question (“These clothes make you feel healthy and attractive”). We tend to default to talking about features, but since most purchases are emotional decisions, it’s much more persuasive to talk about benefits.

Just as you should usually place more emphasis on the benefits of your offering than on the features, you should think about basing the price of your offer on the benefit—not the actual cost or the amount of time it takes to create, manufacture, or fulfill what you are selling. In fact, the

wrong

way to decide on pricing is to think about how much time it took to make it or how much your time is “worth.” How much your time is worth is a completely subjective matter. Bill Clinton makes as much as $200,000 for a single one-hour speech. You might not want to pay Clinton (or any president) $200,000 to speak at your next family pizza night, but for whatever reason, some companies are willing to invest that much.

When you base your pricing on the benefits you provide, be prepared to stand your ground, because some people will always complain about the price being too high no matter what it is. Almost none of the people I met with talked about thriving in their new businesses because they always offered the lowest price. What works for Walmart probably won’t work for you or me. Very few businesses will succeed on the basis of such a cutthroat strategy; that’s why competing on value is so much better.

‡

Gary Leff, the frequent flyer guy who helps busy people book their vacations, charges a flat rate for the service ($250 at press time). Sometimes it takes him a fair amount of work to research and book the trip, but other times he gets lucky and it can take as little as two minutes of research and a ten-minute phone call. Gary

knows that the people he’s booking the trip for don’t care whether it takes ten minutes or two hours; they are paying for his expertise in getting the flights they want.

Time cost: variable, but averages thirty minutes per booking

Benefit: first-class and business-class tickets for worldwide vacations

Cost: $250 (key point: does not vary based on time)

Tsilli Pines, who makes contemporary Judaic stationery, created a Haggadah (a booklet used at the Passover meal) that most frequently is sold in bulk. Single copies are available, but far more people choose a bundle of five or ten.

Materials cost: $3 each

Benefit: nicely designed memento for families to use when observing Passover

Cost to buyers: $14 each (key point: not directly related to the materials cost)

We could trace this theme throughout almost every story in the book. Some examples are even more extreme, especially in information publishing. Every day, people purchase $1,000+ courses that cost virtually nothing to distribute; all the costs are in development and initial marketing. When you think about the price of a new project, ask yourself: “How will this idea improve my customers’ lives, and what is that improvement worth to them?” Then set your price accordingly, while still being clear that the offer is a great value.

Principle 2: Offer a (Limited) Range of Prices

Choosing an initial price for your service that is based on the benefit provided to customers is the most important principle to ensure

profitability. But to create

optimum

profitability or at least to build more cushion into your business model, you’ll next want to present more than one price for your offer. This practice typically makes a huge difference to the bottom line, because it allows you to increase income without increasing your customer base.

Look at Apple, which famously produces very few products and doesn’t bother to compete on price. Even though there are few products, there is always a range of prices and options. You can buy the latest iGadget or computer at the entry level (which, knowing Apple, isn’t cheap), one or more midlevels, or one “superuser” high-end level. The leadership team at Apple—and anyone using a similar model—knows that this kind of pricing allows the company to earn much more money than it otherwise would. This is the case partly because some people will always choose the biggest and best, even if the biggest and best is much more expensive than the regular version. These kinds of sales will increase the overall selling price.

Also, having a high-end version creates an “anchor price.” When we see a superhigh price, we tend to consider the lower price as much more reasonable … thus creating a fair bargain in our minds. The internal thinking goes like this: “Wow, $2 million for the latest MacBook is a lot, but hey, the $240,000 model is almost as good.”

Let’s look at an example of two pricing options: one offered at a set price and one on a tiered structure. Keep in mind that you can substitute any prices here to apply this to another business.

Option 1: The World’s Greatest Widget

Price: $87

Option 1 is simple and presents the choice as follows: Do you want to buy this widget or not?

Here’s an alternative that is almost always better:

Option 2: The World’s Greatest Widget

Choose Your Preferred Widget Option Below

1. Greatest Widget Ever, Budget Version. Price: $87

2. Greatest Widget Ever, Even Better Version. Price: $129

3. Greatest Widget Ever, Exclusive Premium Version. Price: $199

Option 2 presents the choice as follows: Which widget package would you like to buy?

Chances are, some consumers will choose the Exclusive Premium Version, others will choose the Budget Version, but most will opt for the Even Better Version. You don’t want to go too crazy, but you can experiment with this model to add yet another tier in the form of a “

really

premium version” at the top or a “freemium” version at the bottom that lets customers try part of the service without paying anything.

Now let’s look at how the money works out for both of these options.

| Option 1: | | Option 2: |

| 20 sales @ $87 | | 20 sales @ variable prices (14 choose middle, 3 choose budget, 3 choose premium) |

| Total income: $1,740 | | Total income: $2,664 |

| Income per sale: $87 | | Income per sale: $133 |

Difference: $924 total, or $46 per sale

The key to this strategy is to offer a

limited

range of prices: not so many as to create confusion but enough to provide buyers with a legitimate choice. Notice the important distinction that naturally

happens when you offer a choice: Instead of asking them whether they’d like to buy your widget, you’re asking which widget they would like to buy.

Options for creating a price range include: Super-Amazing Version (Gold, First Class, Premium), Product + Setup Help (the same thing sold with special help), and any kind of exclusivity or limited-quantity selection.

You can literally sell the same product at different prices with no other change. As long as you don’t imply that there are added features in the higher-price version, it’s not unethical. Big companies do it all the time; it’s how cell phone carriers, hotels, and airlines make money. To reduce confusion, though, it’s better if you can add something with real value to each higher-level version of the offer.