The 101 Dalmatians (10 page)

Read The 101 Dalmatians Online

Authors: Dodie Smith

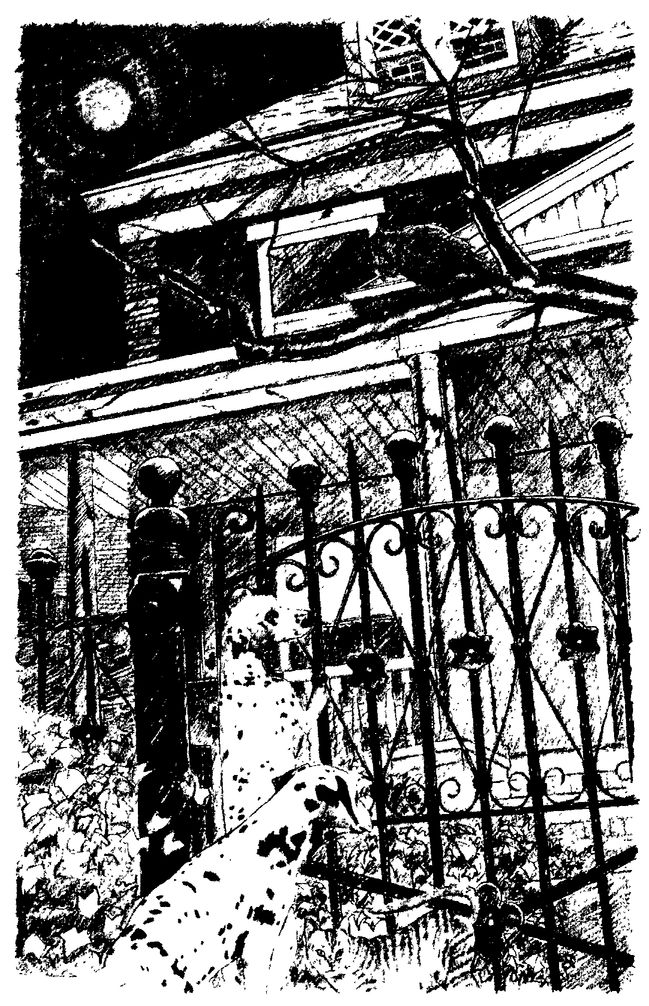

Missis did not know what the word meant, but Pongo had seen a Folly before and was able to explain. The name is often given to expensive, odd buildings built for no sensible reason, buildings that it was a foolishness to build.

The cat miaowed three times, and there were three answering barks from inside the tower. A moment later came the sound of a bolt being drawn back.

“The Colonel's the only dog I ever knew who could manage bolts with his teeth,” said the cat proudly.

Pongo instantly decided

he

would learn to manage bolts.

he

would learn to manage bolts.

“Come in, come in,” said a rumbling voice, “but let me have a look at you first. There's not much light inside yet.”

An enormous Sheepdog came out. Pongo saw at once that this was none of your dapper military men but a lumbering old soldier man, possibly a slow thinker but widely experienced. His eyes glittered shrewdly and kindly through his masses of grey-and-white woolly hair.

“Glad to see you're

large

Dalmatians,” he said approvingly. “I've nothing against small dogs, but the size of all breeds should be kept up. Well, now, what's been happening to you? There was a rare to-do on the Twilight Barking last night, when no one had any news of you.”

large

Dalmatians,” he said approvingly. “I've nothing against small dogs, but the size of all breeds should be kept up. Well, now, what's been happening to you? There was a rare to-do on the Twilight Barking last night, when no one had any news of you.”

He led the way into the Folly, while Pongo told of their day with the Spaniel.

“Sounds a splendid fellow,” said the Colonel. “Sorry he's not on the Barking. Now, tuck in, you two. I provided breakfast just in case you turned up.”

There was plenty of good farmhouse food and a deep round tin full of water.

“How did you get it all here?” asked Pongo astonished.

“I rolled the round tin from the farmâwith the food inside it,” said the Colonel. “I stuffed the tin with straw so that the food wouldn't fall out. And then I borrowed a small seaside bucket from my young pet, Tommyâthe dear little chap would lend me anything. I can carry that bucket by its handle. Six trips to the pond on the heath got the water hereâlucky it thawed yesterday. Drink up! Plenty more where that came from.”

The cat acted as hostess during the meal. Pongo was careful always to address her as “Mrs. Willow.”

“What's this Mrs. Willow business?” said the Colonel suddenly.

“Pussy Willow happens to be my given name,” said the cat. “And I'm certainly a Mrs.”

“You've got too many names,” said the Colonel. “You're âPuss' because all cats are 'Puss.â You're 'Pussy Willow' because it's your given name. You're âTib' because most people call you that.

I

call you 'Lieutenant' or âLieutenant Tib.' I thought you liked it.”

I

call you 'Lieutenant' or âLieutenant Tib.' I thought you liked it.”

“I like âLieutenant' but not 'Lieutenant Tib.â ”

“Well, you can't be â

Mrs.

Willow' on top of everything else. You can't have six names.”

Mrs.

Willow' on top of everything else. You can't have six names.”

“I'm entitled to nine names as I've nine lives,” said the cat. “But I'll settle for âLieutenant Willow'âwith âPuss' for playful moments. ”

“Right,” said the Colonel. “And now we'll show our guests their sleeping quarters.”

“Oh, please,” begged Missis. “Couldn't we get just a glimpse of the puppies before we sleep?”

The cat shot a quick look at the Colonel and said, “I've told them the pups won't be out for hours yet.”

“Besides, you'd get too excited to sleep,” said the Colonel. “You must both have a good rest before you start worrying.”

“Worrying?” said Pongo sharply. “Is something wrong?”

“I give you my word there is nothing wrong with your puppies,” said the Colonel.

Pongo and Missis believed himâand yet they both thought there was something odd about his voice, and about the look the cat had given him.

“Now up we go,” the Colonel went on briskly. “You're sleeping on the top floor because that's the only floor where the windows aren't broken. Want a ride Lieutenant WibâI mean Lieutenant Tillowâoh, good heavens, cat!”

“If there's one thing I object to being called, it's plain âcat,'” said the cat.

“Quite right. I don't like being called plain âdog,' ” said the Colonel. “I apologize, Lieutenant Willow. Now jump on my back unless you want to walk.”

The cat jumped on the Colonel's back and held on by his long hair. Pongo had never before seen a cat jump on a dog's back with friendly intentions. He was deeply impressed-both by the Colonel's trustfulness and the cat's trustworthiness.

The narrow, twisting stairs went up through five floors of the Folly, most of them full of broken furniture, old trunks, and all manner of rubbish. On the top floor was a deep bed of straw, brought up by the Colonel in a sack. But what interested Missis far more was the narrow windowâsurety it must look towards Hell Hall?

She ran to see. Yes, beyond the tree-tops and a neglected orchard was the back of the black houseâwhich was as ugly as the front, though it did not have such a frightening expression. At one side was a large stableyard.

“Is that where the puppies will come out?” she asked.

“Yes, yes,” said the Colonel, “but it won't be forâwe!!, for some time yet.”

“I shall never sleep until I've seen them,” said Missis.

“Yes, you will, because I shall talk you to sleep,” said the Colonel. “Your husband has asked me to tell him the history of Hell Hall. Now come and lie down.”

Pongo was as anxious to see the puppies as Missis was, but he knew they should sleep first, so he coaxed her to lie down. The Colonel pulled the straw round both of them.

“It's chilly in hereânot that

I

feel it,” he said. Then he sent the cat to start collecting food for the next meal, and began to talk in his rumbling voice. This was the story he told.

I

feel it,” he said. Then he sent the cat to start collecting food for the next meal, and began to talk in his rumbling voice. This was the story he told.

Hell Hall had once been an ordinary farmhouse named Hill Hallâit had been built by a farmer named Hill. It was about two hundred years old, the same age as the farm where the Sheepdog and the cat lived.

“The two houses are quite a bit alike,” said the Colonel, “only our place is painted white and well cared for. I remember Hell Hall before it was painted black and it really wasn't bad at all.”

The farmer named Hill had got into debt and sold Hill Hall to an ancestor of Cruella de Vilâs, who liked its lonely position on the wild heath. He intended to pull the farmhouse down and build himself a fantastic house which was to be a mixture of a castle and a cathedral, and had begun by building the surrounding wall and the Folly. (The Colonel had heard all this while visiting the Vicarage.)

Once the wall, with its heavy iron gates, was finished, strange rumours began to spread. Villagers crossing the heath at night heard screams and wild laughter. Were there prisoners behind the prison-like wall? People began to count their children carefully.

“Some of the storiesâWell, I shan't tell you just as you're falling asleep,” said the Colonel. “I didn't hear them at the Vicarage. But I will tell you somethingâbecause it won't upset you as it naturally upset the villagers. It was said that this de Vil fellow had a long tail. I didn't hear that at the Vicarage, either.”

Missis had taken in very little of this and was now fast asleep, but Pongo was keenly interested.

“By this time,” the Colonel went on, “people were calling the place Hell Hall, and the de Vil chap plain devil. The end came when the men from several villages arrived one night with lighted torches, prepared to break open the gates and burn the farmhouse down. But as they approached the gates a terriffic thunderstorm began and put the torches out. Then the gates burst openâseemingly of their own accordâand out came de Vil, driving a coach and four. And the story is that lightning was coming not from the skies but from de Vilâblue forked lightning. All the men ran away screaming and never came back. And neither did de Vil. The house stood empty for thirty years. Then someone rented it. It's been rented again and again, but no one ever stays.”

“And it still belongs to the de Vil family?” asked Pongo.

“There's only Cruella de Vil left of the family now. Yes, she owns it. She came down here some years ago and had the house painted black. It's red inside, I'm told. But she never lived here. She lets the Baddun brothers have it rent free, as caretakers. I wouldn't let them take care of any kennel of mine. ”

Those were the last words Pongo heard, for, as the story ended, sleep wrapped him round. The Sheepdog stood looking down at the peaceful couple.

“Well, they're in for a shock,” he thought, and then lumbered his way downstairs.

It was less than an hour later when Missis opened her eyes. She had been dreaming of the puppies, she had heard them barkingâand they

were

barking! She sprang out of the straw and dashed to the window. No pup was to be seen, but she could hear the barking clearlyâit was coming from inside the black house. Then the barking grew louder, the door to the stableyard opened, and out came a stream of puppies.

were

barking! She sprang out of the straw and dashed to the window. No pup was to be seen, but she could hear the barking clearlyâit was coming from inside the black house. Then the barking grew louder, the door to the stableyard opened, and out came a stream of puppies.

Missis blinked. Surely her puppies could not have grown so much in less than a week? And surely she had not had so many puppies? More and more were hurrying out; the whole yard was filling up with fine, large, healthy Dalmatian puppies, butâ

Missis raised her head in a wail of despair. These puppies were not hers at all! The whole thing was a mistake! Her puppies were still lost, perhaps starving, perhaps even dead. Again and again she howled in anguish.

Her first howl had wakened Pongo. He was beside her in a couple of seconds and staring at the yard full of milling, tumbling puppies. And they were still coming out of the house, rather smaller puppies nowâ

And then they saw himâsmaller, even, than they had remembered. Lucky! There was no mistaking that horseshoe of spots on his back. And after him came Roly Poly, falling over his feet as usual. Then Patch and the tiny Cadpig and all the othersâall well, all lashing their tails, all eager to drink at the low troughs of water that stood about in the yard.

“Look, Patch is helping the Cadpig to find a place,” said Missis delightedly. “But what does it mean? Where have all those other puppies come from?”

Dazed as he was with sleep, Pongo's keen brain had gone into instant action. He saw it all. Cruella must have begun stealing puppies months beforeâsoon after that evening when she had said she would like a Dalmatian fur coat. The largest pups in the yard looked at least five months old. Then they went down and down in size. Smallest and youngest of all were his own puppies, which must obviously have been the last to be stolen.

He had barely finished explaining this to Missis when the Sheepdog reached the top of the stairsâhe had been downstairs getting in fresh water and had heard Missis howl.

“Well, now you know,” he said. “I was hoping you could have had your sleep out first.”

“But why are you both looking so worried?” asked Missis. “Our puppies are safe and well.”

“Yes, my dear. You go on watching them,” said Pongo gently. Then he turned to the Colonel.

You come downstairs and have a drink, my boy,“ said the Colonel.

In the Enemys Camp

OH, how Pongo needed that drink!

“And now stroll down to the pond with me,” said the Colonel, gripping the handle of a little tin bucket in his teeth. “You won't feel like trying to sleep any more just at present.”

Pongo felt he would never be able to sleep again.

“I blame myself for letting you in for this shock,” said the Colonel as they went out into the early morning sunlight. “Because you can't blame the Lieutenant. She's not a trained observer. When she told me the place was âseething with Dalmatian puppies' I naturally thought she meant your puppies only. After all, fifteen puppies can do quite a bit of seething. It was only yesterday, after I'd made the Folly my headquarters and could see over the wall, that I found out the true facts. Of course I sent the news over yesterday's Twilight Barking but couldn't reach you.”

“How many puppies are there?” asked Pongo.

“Can't tell, exactly, because they never keep still. But I'd sayâcounting yoursâgetting on for a hundred.”

“A

hundred?”

hundred?”

They had reached the pond. “Have another drink,” suggested the Colonel.

Pongo gulped down some more water, then stared hopelessly at the Sheepdog.

“Colonel, what am I going to do?”

“Will your lady wife want just to rescue her own puppies?”

“She may at first,” said Pongo. “But not when she realizes it would mean leaving all the others to certain death.”

“Anyway, your pups aren't old enough for the journey,” said the Colonel. “I suppose you know that?”

Other books

Riss Series 5: The Riss Challenge by C. R. Daems

Captain's Surrender by Alex Beecroft

The White Guard by Mikhail Bulgakov

Treasure of Love by Scotty Cade

The Swiss Family RobinZOM (Book 3) by Perrin Briar

Longing for Kayla by Lauren Fraser

Azaria by J.H. Hayes

The Last American Martyr by Tom Winton

Mixed Messages (A Malone Mystery) by Gligor, Patricia