The 101 Dalmatians (7 page)

Read The 101 Dalmatians Online

Authors: Dodie Smith

And he knew, though he kept this from Missis, that the S.O.S. on the old bone meant “Save Our Skins.”

At the Old Inn

PONGO had no difficulty in taking the right road out of London, for he and Mr. Dearly had done much motoring in their bachelor days and often driven to Suffolk. Mile after mile the two dogs ran through the deserted streets, as the December night grew colder. At last London was left behind and, just before dawn, they reached a village in Epping Forest where they hoped to spend the day.

They had decided they must always travel by night and rest during daylight. For they felt sure Mr. Dearly would advertise their loss and the police would be on the lookout for them. There was far less chance of their being seen and caught by night.

They had barely entered the sleeping village when they heard a quiet bark. The next moment a burly Golden Retriever was greeting them.

“Pongo and Missis Pongo, I presume? All arrangements were made for you by Late Twilight Barking. Please follow me.”

He led them to an old gabled inn and then under an archway to a cobbled yard.

“Please drink here, at my own bowl,” he said. “Food awaits you in your sleeping quarters, but water could not be arranged.”

(For no dog can carry a full water-bowl.)

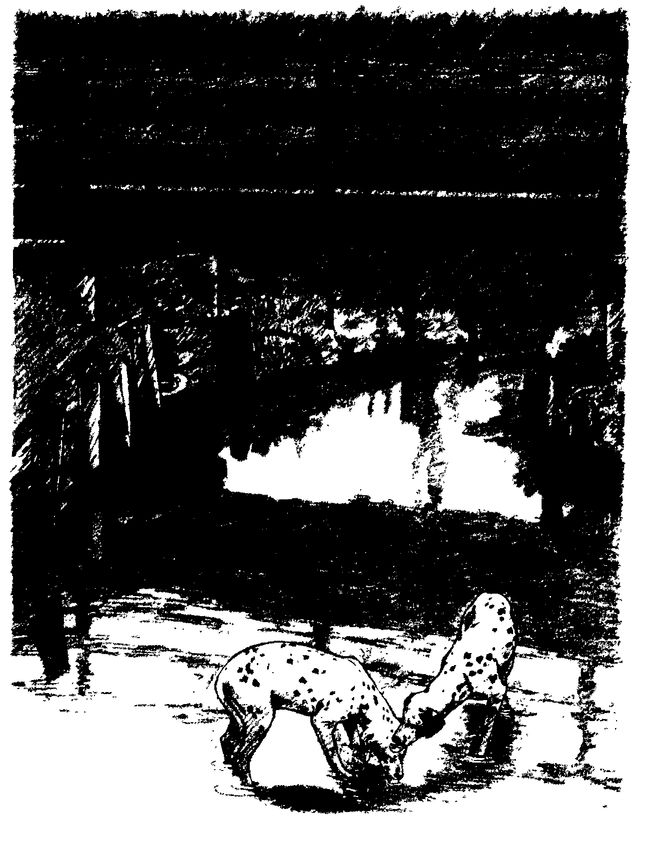

Pongo and Missis had had only one drink since they left home, at an old drinking trough for horses, which had a lower trough for dogs. They now gulped thirstily and gratefully.

“My pride as an innkeeper tempts me to offer you one of our best bedrooms,” said the Golden Retriever. “They combine old-world charm with all modern conveniencesâand no charge for breakfast in bed. But it wouldn't be wise.”

“No, indeed,” said Pongo. “We might be discovered.”

“Exactly. We are putting you in the safest place any of us could think of. Naturally every dog in the village came to the meeting after the Late Barkingâwhen we heard this village was to have the honour of receiving you. Step this way.”

At the far end of the yard were some old stables, and in the last stable of all was a broken-down stagecoach.

“Just the right place for Dalmatians,” said Pongo, smiling, “for our ancestors were trained to run behind coaches and carriages. Some people still call us Coach Dogs or Carriage Dogs.”

And your run from London has shown you are worthy of your ancestors,“ said the Golden Retriever. ”When I was a pup we sometimes took this old coach out for the school picnic, but no one has bothered with it for years now. You should be quite safe, and some dogs will always be on guard. In case of sudden alarm, you can go out by the back door of the stable and escape across the fields.“

There was a deep bed of straw on the floor of the coach, and neatly laid out on the seat were two magnificent chops, half a dozen iced cakes, and a box of peppermint creams.

“From the butcher's dog, the baker's dog, and the dog at the sweet-shop,” said the Retriever. “I shall arrange your dinner. Will steak be satisfactory?”

Pongo and Missis said it would indeed, and tried to thank him for everything, but he waved their thanks away, saying, “It's a very great honour. We are planning a small plaqueâto be concealed from human eyes, of courseâ

saying:

PONGO AND MISSIS SLEPT HERE.”

saying:

PONGO AND MISSIS SLEPT HERE.”

Then he took them to the cobwebbed window and pointed out a smaller edition of himself, who was patrolling the inn courtyard.

My youngest lad, already on guard. He's hoping to see you for a moment, when you're rested, and ask for your paw-marksâto start his collection. A small guard of honour will see you out of the village, but I shan't let them waste too much of your time. Good nightâthough it's really good morning. Pleasant dreams.“

As soon as he had gone, Pongo and Missis ate ravenously.

“Though perhaps we should not eat

too

heavily before going to sleep,” said Pongo, so they left a couple of peppermint creams. (Missis later ate them in her sleep.) Then they settled down in the straw, close together, and got warmer and warmer.

too

heavily before going to sleep,” said Pongo, so they left a couple of peppermint creams. (Missis later ate them in her sleep.) Then they settled down in the straw, close together, and got warmer and warmer.

Missis said, Do you feel

sure

our puppies will be well fed and well taken care of?“

sure

our puppies will be well fed and well taken care of?“

“Quite

sure. And they will be safe for a long time, because their spots are nowhere near big enough for a striking fur coat yet. Oh, Missis, how pleasant it is to be on our own like this!”

sure. And they will be safe for a long time, because their spots are nowhere near big enough for a striking fur coat yet. Oh, Missis, how pleasant it is to be on our own like this!”

Missis thumped her tail with joyâand with relief. For there had been moments when she had feltânot jealous, exactly, but just a bit

wistful

about Pongo's affection for Perdita. She loved Perdita, was grateful to her and sorry for her; stillâwell, it was nice to have her own husband to herself, thought Missis. But she made herself say, “Poor Perdita! No husband, no puppies! We must never let her feel we want to be on our own.”

wistful

about Pongo's affection for Perdita. She loved Perdita, was grateful to her and sorry for her; stillâwell, it was nice to have her own husband to herself, thought Missis. But she made herself say, “Poor Perdita! No husband, no puppies! We must never let her feel we want to be on our own.”

“I do hope she can comfort the Dearlys,” said Pongo.

“She will

wash

them,” said Missisâand fell asleep.

wash

them,” said Missisâand fell asleep.

How gloriously they slept! It was their first really deep sleep since the loss of the puppies. Even the Twilight Barking did not disturb them. It brought good news, which the Retriever told them when he woke them, as soon as it was dark. All was well with the pups, and Lucky sent a message that they were getting more food than they could eat. This gave Pongo and Missis a wonderful appetite for the steaks that were waiting for them.

While they ate, they chatted to the Retriever and his wife and their family, who lived at various houses in the village. And the Retriever told Pongo how to reach the village where the next day was to be spentâthis had been arranged by the Twilight Barking. The steaks were finished and a nice piece of cheese was going down well when the Corgi from the post office arrived with an evening paper in her mouth. Mr. Dearly had put in his largest advertisement yetâwith a photograph of Pongo and Missis (taken during the joint honeymoon).

Pongo's heart sank, for he felt the route planned for them was no longer safe. It led through many villages, where even by night they might be noticedâunless they waited till all humans had gone to bed, which would waste too much time. He said, “We must travel across country.”

“But you'll get lost,” said the Retriever's wife.

“Pongo never loses his way,” said Missis proudly.

“And the moon will be nearly full,” said the Retriever. “You should manage. But it will be hard to pick up food. I had arranged for it to await you in several villages.”

Pongo said they had eaten so much that they could do without food until the morning, but he hated to think dogs might be waiting up for them during the night.

“I will cancel it by the Nine-oâclock Barking,” said the Retriever.

There was a snuffling at the back door of the stable. All the dogs of the village had arrived to see Pongo and Missis off.

“We should start at once,” said Pongo. “Where's our young friend who wants paw-marks?”

The Retriever's youngest lad stepped forward shyly, carrying an old menu. Pongo and Missis put their pawtographs on the back of it for him, then thanked the Retriever and his family for all they had done.

Outside, two rows of dogs were waiting to cheer. But no human ear could have heared the cheers, for every dog had now seen the photograph in the evening paper and knew an escape must be made in absolute silence.

Pongo and Missis bowed right and left, gratefully sniffing their thanks to all. Then, after a last good-bye to the Retriever, they were off across the moonlit fields.

“On to Suffolk!” said Pongo.

Cross Country

THEY were well rested and well fed, and they soon reached a pond where they could drinkâthe Retriever had told them to be on the lookout for it. (It would not have been safe for them to drink from his bowl again; too many humans were now about.) And their spirits were far higher than when they had left the house in Regent's Park. How far away it already seemed, although it was less than twenty-four hours since they had been in their baskets by the kitchen fire. Of course they were still anxious about their puppies, and sorry for the poor Dearlys. But Lucky's message had been cheering, and they hoped to make it all up to the Dearlys one day. And anyway, as Pongo said, worrying would help nobody, while enjoying their freedom to race across the fields would do them a power of good.

He was relieved to see how well Missis ran and what good condition she was in. So much food had been given to her while she was feeding the puppies that she had never got pitifully thinâas Perdita had when she had fed her own puppies without being given extra food.

“You are a beautiful dog, Missis,” said Pongo. “I am very proud of you.”

At this, Missis looked even more beautiful and Pongo felt even prouder of her. After a minute or so, he said, “Do you think

I'm

looking pretty fit?”

I'm

looking pretty fit?”

Missis told him he looked magnificent, and wished she had said so without being asked. He was not a vain dog, but every husband likes to know that his wife admires him.

They ran on, shoulder to shoulder, a perfectly matched couple. The night was windless and therefore seemed warmer than the night before, but Pongo knew there was a heavy frost; and when, after a couple of hours across the fields, they came to another pond, there was a film of ice over it. They broke this easily and drank, but Pongo began to be a little anxious about where they would be by daybreak, for they would need good shelter in such cold weather. As they were now travelling across country, he thought it unlikely they would find the village that had been expecting them, but he felt sure most dogs would by now have heard of them and would be willing to help. “Only we must be near some village by dawn, or we shall meet no dogs,” he thought.

Soon after that a lane crossed the fields and, as they had just heard a church clock strike midnight, Pongo felt there was now little chance of their meeting any humans on the road. He wanted to find a signpost and make sure they were travelling in the right direction. So they went along the lane for a mile until they came to a sleeping village. There was a signpost on the green, which Pongo read by the light of the moon. (He was very good at readingâas a pup he had played with alphabet blocks.) All was well. Their journey across the fields had saved them many miles, and they were now deep in Essex. (The village where they might have stayed was already behind them.) By going north, they would reach Suffolk.

The only depressing thing was that the wonderful steak dinner seemed such a long time ago, And there was no hope of getting food as late as this. They just had to go on and on through the night, getting hungrier and hungrier.

And by the time it began to get light, they were also extremely chillyâpartly because they were hungry and tired and partly because it was getting colder and colder. The ice on the ponds they passed was thicker and thickerâat last they came to a pond where they could not break through to drink.

And now Pongo was really anxious, for they had reached a part of the country where there seemed to be very few villages. Where could they get food and shelter? Where could they hide and sleep during the bitterly cold day ahead of them?

He did not tell Missis of his fears and she would not even admit that she was hungry. But her tail drooped and her pace got slower and slower. He felt terrible: tired, hungry, anxious, and deeply ashamed that he was letting his beautiful wife suffer hardship. Surely there would be a village soon, or a fair-sized farm?

“Should we rest a little now, Pongo?” said Missis at last.

âNot until we've found some dogs to help us, Missis,“ said Pongo. Then his heart gave a glad leap. Ahead of them were some thatched cottages! It was full daylight now, and he could see smoke twisting up from several chimneys. Surely some dog would be about.

If anyone tries to catch us, we must take to the fields and run,“ said Pongo.

“Yes, Pongo,” said Missis, though she did not now feel she could run very far.

They reached the first cottage. Pongo gave a low bark. No dog answered it.

They went on and soon saw that this was not a real village but just a short row of cottages, some of them empty and almost in ruins. Except for smoke rising from a few chimneys, there was no sign of life until they came to the very last cottage. As they reached it a little boy looked out of a window.

He saw them and quickly opened the cottage door. In his hand was a thick slab of bread and butter. He appeared to be holding it out to them.

“Gently, Pongo,” said Missis, “or we shall frighten him.”

They went through the open gate and up the cobbled path, wagging their tails and looking with love at the little boyâand the bread and butter. The child smiled at them fearlessly and waved the bread and butter. And then, when they were only three or four yards away, he stooped, picked up a stone, and slung it with all his force. He gave a squeal of laughter when he saw the stone strike Pongo, then went in and slammed the door.

Other books

NEW WORLD TRILOGY (Trilogy Title) by Nelson, Olsen J.

ACCORDING TO PLAN by Barr, Sue

Unbroken by Paula Morris

The Labyrinth of the Dead by Sara M. Harvey

Figure 8 by Elle McKenzie

The Secret of Spring by Piers Anthony, Jo Anne Taeusch

Murder In Chinatown by Victoria Thompson

Rat Bohemia by Sarah Schulman

Silent Noon by Trilby Kent