The a to Z Encyclopedia of Serial Killers (3 page)

Read The a to Z Encyclopedia of Serial Killers Online

Authors: Harold Schechter

Tags: #True Crime, #General

Animal torture is, in fact, such a common denominator in the childhoods of serial killers that it is considered one of the three major warning signals of future psychopathic behavior, along with unnaturally prolonged bed-wetting and juvenile pyromania (see

Triad

).

The vast majority of little boys who get their kicks from dismembering daddy longlegs or dropping firecrackers into anthills lose their stomach for sadism at an early age. The case is very different with incipient serial killers. Fixated at a shockingly primitive stage of emotional development, they never lose their craving for cruelty and domination. Quite the contrary: it continues to grow in them like a cancer. Eventually—when dogs, cats, and other small, four-legged creatures can no longer satisfy it—they turn their terrifying attentions to a larger, two-legged breed: human beings.

A

RISTOCRATS

For the most part, the only truly remarkable thing about modern-day serial killers is their grotesque psychopathology. Otherwise, they tend to be absolute nobodies. It is precisely for this reason that they are able to get away with murder for so long. No one looking at, say, Joel Rifkin—the Long Island landscape gardener who slaughtered a string of prostitutes and stored their bodies in the suburban home he shared with his adoptive parents—would ever suspect that this utterly nondescript individual was capable of such atrocities.

For many serial killers, in fact, the notoriety they achieve through their crimes is, if not their main motivation, then certainly an important fringe benefit. Murder becomes their single claim to fame—the only way they have

of getting their names in the paper, of proving to the world (and to themselves) that they are “important” people.

In centuries past, the situation was frequently different. Far from being nonentities, the most notorious serial killers of medieval times were people of great prominence and power. The most infamous of these was the fifteenth-century nobleman Gilles de Rais. Heir to one of the great fortunes of France, Gilles fought alongside Joan of Arc during the Hundred Years War. For his courage in battle, he was named marshal of France, his country’s highest military honor.

Following Joan’s execution in 1431, however, Gilles returned to his ancestral estate in Brittany and plunged into a life of unspeakable depravity. During a nine-year reign of terror, he preyed on the children of local peasants. Unlike today’s low-born serial killers, the aristocratic Gilles didn’t have to exert himself to snare his victims; his servants did it for him. Whisked back to his horror castle, the children (most of them boys) were tortured and dismembered for the delectation of the “Bestial Baron,” who liked to cap off his pleasure by violating their corpses. Executed in 1440, he is widely regarded as the model for the fairy-tale monster

Bluebeard

.

A female counterpart of Gilles was the Transylvanian noblewoman Elizabeth Bathory, a vampiric beauty who believed she could preserve her youth by bathing in the blood of virgins. According to conservative estimates, Bathory butchered and drained the blood of at least forty young women before her arrest in 1610.

Her tally was topped by her near contemporary, the French noblewoman Marie Madeleine d’Aubray, marquise de Brinvilliers. Having run through a fortune, this profligate beauty decided to knock off her father in order to get her hands on his estate. In her efforts to concoct an indetectable poison, she volunteered her services at the Hôtel Dieu—Paris’s public hospital—and began trying out different formulas on her patients, ultimately dispatching at least fifty of them. In 1676, she was beheaded for her crimes.

Closer to our own time, some

Jack the Ripper

buffs (or “Ripperologists,” as they prefer to be called) speculate that the legendary “Butcher of Whitechapel” was actually Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence, Queen Victoria’s grandson and heir to the throne of England. As tantalizing as this theory sounds, it is almost certainly a complete fantasy, akin to the wilder Kennedy assassination scenarios. The unglamorous truth is that Jack was probably

nothing more than a knife-wielding nobody—just like the scores of hideously sick nonentities who have followed in his bloody footsteps.

A

RT

Serial killer art can be divided into two major categories: (1) works of art

about

serial killers, and (2) works of art

by

serial killers.

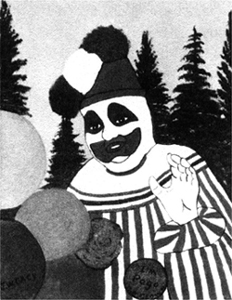

To start with the latter: the best known of all serial killer artists was John Wayne

Gacy

, who began dabbling in oil painting while in prison. Though Gacy painted everything from Disney characters to Michelangelo’s

Pietà,

his trademark subject was Pogo the Clown—the persona he adopted during his prearrest years, when he would occasionally don circus makeup and entertain the kids at the local hospital. Gacy’s amateurish oils could be had for a pittance a decade ago, but their value increased as they became trendy collectibles among certain celebrities, like film director John Waters and actor Johnny Depp. Since Gacy’s execution, the price for his paintings has shot even higher. While some of his oils are explicitly creepy (like his so-called Skull Clown paintings), even his most “innocent”—like his depictions of Disney’s Seven Dwarves—have an ineffable malevolence to them.

Pogo the Clown;

painting by John Wayne Gacy

(Courtesy of Mike Ferris)

For a while, Gacy’s exclusive art dealer was the Louisiana funeral director and serial killer enthusiast Rick Staton (see

The Collector

). Under Staton’s encouragement, a number of other notorious murderers have taken up prison arts and crafts. Staton—who started a company called Grindhouse Graphics to market this work and has staged a number of Death Row Art Shows in New Orleans—has represented a wide range of quasicreative killers, including Richard “Night Stalker”

Ramirez

(who does crude but intensely spooky ballpoint doodles); Charles

Manson

(who specializes in animals sculpted from his old socks); and Elmer Wayne Henley. Henley—who, along with his buddy Dean Corll, was responsible for the torture-murder of as many as thirty-two young men—likes to paint koala bears.

As devoted as he is to promoting the work of these people, even Staton concedes that they possess no artistic talent. There are a couple of exceptions, however. Lawrence Bittaker—who mutilated and murdered five teenage girls—produces some truly original pop-up greeting cards. The most gifted of the bunch, however, is William Heirens, the notorious “Lipstick Killer,” who has been in prison since 1946 and who paints exquisitely detailed watercolors.

As far as serious art goes (i.e., art about, not by, serial killers), painters have been dealing with horrific sex crimes since at least the nineteenth century. The Victorian artist Walter Sickert, for example, did such disturbing pictures of murdered prostitutes that crime writer Patricia Cornwell has accused him of being

Jack the Ripper

.

Scholars have also discovered that, in addition to the post-Impressionist landscapes and still lifes he’s best known for, Paul Cézanne did a whole series of paintings and drawings depicting grisly sex crimes.

Throughout the twentieth century, hideous murder often appears as a subject of serious art. In

The Threatened Assassin,

a 1926 painting by Surrealist René Magritte, a bowler-hatted man wields a clublike human limb while a nude woman lies bleeding in the background. Even more unsettling is Frida Kahlo’s 1935

A Few Small Nips,

in which a gore-drenched killer, clutching a knife, stands at the bedside of his savaged girlfriend. In 1966, the German postmodern painter Gerhard Richter caused an uproar when he displayed his

Eight Student Nurses,

realistic portraits of Richard

Speck

’s victims, based on their yearbook photos. That controversy was minor, however, compared to the outcry provoked in 1997, when a highly publicized British art show included Marcus Harvey’s

Myra

—an enormous

portrait of the notorious

Moors Murderer

created from the handprints of children.

Of all serial murder paintings produced in the twentieth century, probably the greatest are those by Otto Dix, the famous German Expressionist who was obsessed with images of sadistic sexual mutilation and produced a series of extraordinary canvases on the subject. His contemporary George Grosz (who posed as Jack the Ripper in a famous photographic self-portrait) also created a number of works about sex-related killings, including the harrowing

Murder on Acker Street,

which depicts a cretinous killer scrubbing his hands after decapitating a woman, whose horribly mangled corpse occupies the center of the picture. (If you’re interested in a brilliant study of sexual murder in Weimar Germany—which reproduces several dozen works by Dix and Grosz—check out the 1995 book

Lustmord

by Harvard professor Maria Tartar.)

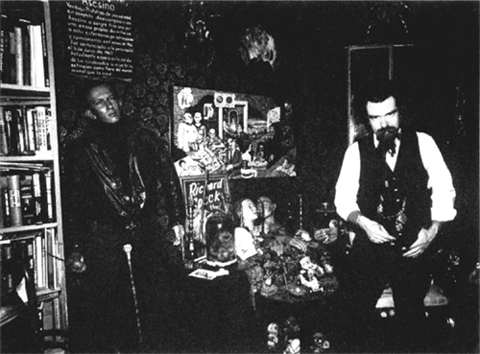

The spiritual heir of Dix and Grosz is Joe Coleman, America’s preeminent painters of serial killers (see

The Apocalyptic Art of Joe Coleman

). Coleman’s work has inspired a number of younger artists, including the young Brooklyn painter Michael Rose, whose subjects range from religious martyrdoms to grisly accidents to the atrocities of Albert

Fish

.

Another Brooklyn artist, Chris Pelletiere, has done a series of stunning portraits of some of America’s most notorious killers, including Charles Starkweather, Henry Lee

Lucas

, and Ed

Gein

.

Finally, there is the well-known Pop surrealist Peter Saul. Now in his sixties, Saul has been offending sensibilities for the past three decades with canvases like

Donald Duck Descending a Staircase, Puppy in an Electric Chair,

and

Bathroom Sex Murder.

Rendered in a garish, cartoony style, Saul’s recent paintings of serial killers—which include grotesque depictions of John Wayne

Gacy

’s execution and Jeffrey

Dahmer

’s eating habits—are among his most electrifying works.

The Apocalyptic Art of Joe Coleman

America’s premier painter of serial killers, Joe Coleman is also the only significant artist ever to perform as a geek. Indeed, one of his most powerful self-portraits—

Portrait of Professor Momboozoo

—shows the crucified Coleman

with a bitten-off rat’s head jutting from his mouth. Like so much of Coleman’s work, it’s an astounding image, one that sums up three of the major themes of his art: horror, sideshow sensationalism, and (insofar as devouring the body and blood of a rodent represents a grotesque parody of the Last Supper) religious obsession.