The a to Z Encyclopedia of Serial Killers (6 page)

Read The a to Z Encyclopedia of Serial Killers Online

Authors: Harold Schechter

Tags: #True Crime, #General

B

LASPHEMY

For the most part, this is an outrage perpetrated by devil-worshipping cultists who delight in blaspheming the orthodox rituals of Christianity (see

Satanism

). The central ceremony of satanic worship, for example, is the so-called Black Mass, an obscene travesty of the Catholic mass involving baby sacrifice, orgiastic sex, and other abominations.

There is, however, at least one serial killer who added blasphemy to his staggering list of outrages. After murdering his final victim—an eighty-eight-year-old grandmother named Kate Rich—Henry Lee

Lucas

carved an upside-down cross between the old woman’s breasts. Then he raped her corpse.

R

OBERT

B

LOCH

Say the word

psycho

to most people and they will immediately visualize scenes from the classic horror film: Janet Leigh getting slashed to pieces in a shower, Martin Balsam being set upon by an old biddy with a butcher knife, Anthony Perkins smiling insanely while a fly buzzes around his padded cell. But while it was Alfred Hitchcock’s genius that made

Psycho

into a masterpiece, it was another imagination that first dreamed up Norman Bates and his motel from hell. It belonged to Robert Bloch, one of the most prolific and influential horror writers of the century.

Born in Chicago in 1917, Bloch began publishing stories in the pulps while still a teenager. He received encouragement from his pen pal and muse, horrormeister H. P. Lovecraft (who named a character after Bloch in his story “The Haunter of the Dark”). After working as an advertising copywriter in Milwaukee, Bloch quit to become a full-time writer in the early 1950s. He specialized in tales whose macabre twist endings make them read like extended sick jokes. Psychopathic killers figure prominently in his fiction. One of his best-known stories is titled, “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper.”

In 1957, Bloch—who had relocated to Los Angeles to write screenplays—moved back to Wisconsin so that his ailing wife could be close to her parents. He was living in the town of Weyauwega, less than thirty miles from Plainfield, where police broke into the tumbledown farmhouse of a middle-aged bachelor named Edward

Gein

and discovered a collection of horrors that sent shock waves around the nation. Fascinated by the incredible circumstances of the Gein affair—particularly by the fact (as he later put it) “that a killer with perverted appetites could flourish almost openly in a small rural community where everybody prides himself on knowing everybody else’s business”—Bloch hit on the idea for a horror novel. The result was his 1959 thriller,

Psycho,

about the schizophrenic mama’s boy, Norman Bates—a monster who (like Dracula and King Kong) has become a permanent icon of our pop mythology.

Bloch wrote hundreds of short stories and more than twenty novels, in addition to dozens of screenplays and television scripts. However, when he died, on September 23, 1994, the headlines of his obituaries invariably identified him (as he predicted they would) as the “Author of

Psycho.”

As interpreted by Hitchcock, this pioneering piece of serial-killer literature set the pattern for all cinematic slasher fantasies of the past forty-six years. In

spite of his lifelong obsession with psychopathic killers, Bloch himself was the gentlest of men, who had little use for the kind of graphically gory horror movies his own work had inspired. When asked his opinion of films like

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre,

the man who gave birth to Norman Bates admitted, “I’m quite squeamish about them.”

B

LUEBEARDS

Reputedly modeled on the fifteenth-century monster Gilles de Rais (see

Aristocrats

), the folktale character Bluebeard is a sinister nobleman who murders a succession of wives and stores their corpses in a locked room in his castle. In real life, the term is used to describe a specific type of serial killer who, like his fictional couterpart, knocks off one wife after another.

There are two major differences between a Bluebeard killer and a psycho like Ted

Bundy

.

The latter preys on strangers, whereas the Bluebeard type restricts himself to the women who are unlucky (or foolish) enough to wed him. Their motivations differ, too. Bundy and his ilk are driven by sexual sadism; they are lust murderers. By contrast, the cardinal sin that motivates the Bluebeard isn’t lust but greed. For the most part, this kind of serial killer dispatches his victims for profit.

The most infamous Bluebeard of the twentieth century was a short, balding, red-bearded Frenchman named Henri Landru (the real-life inspiration for Charlie Chaplin’s black comedy

Monsieur Verdoux).

In spite of his unsightly appearance, Landru possessed an urbane charm that made him appealing to women. It didn’t hurt, of course, that there were so many vulnerable women around—lonely widows of the millions of young soldiers who had perished on the battlefields of World War I. An accomplished swindler who had already been convicted seven times for fraud, Landru found his victims by running matrimonial

Ads

in the newspapers. When a suitable (i.e., wealthy, gullible) prospect responded, Landru would woo her, wed her, assume control of her assets, then kill her and incinerate the corpse in a small outdoor oven on his country estate outside Paris. He was guillotined in 1922, convicted of eleven murders—ten women, plus one victim’s teenaged son.

Even more prolific was a German named Johann Hoch, who emigrated to America in the late 1800s. In sheer numerical terms, Hoch holds some

sort of connubial record among Bluebeards, having married no fewer than fifty-five women, at least fifteen of whom he dispatched. Like Landru, he never confessed, insisting on his innocence even as the hangman’s noose tightened around his neck.

Victorian engraving, showing Bluebeard’s collection of chopped-off female heads.

Another notorious Bluebeard from across the sea was the Englishman George Joseph Smith, who became known as the “Brides in the Bath” murderer for his habit of drowning his wives in the tub in order to collect on their life insurance. Like Landru and Hoch, Smith vehemently proclaimed his innocence, leaping up during his trial and shouting, “I am not a murderer, though I may be a bit peculiar!” The jury didn’t buy it, at least the first part. He was hanged on Friday, August 13, 1915.

Though the killer who snares his female victims with his suave, attentive manners seems quintessentially European, our own country has produced its share of Bluebeards. Born and bred in Kansas, Alfred Cline looked like a Presbyterian minister—one of the reasons, no doubt, that he was able to

win the trust of so many well-to-do widows, eight of whom he married and murdered between 1930 and 1945. Even Cline’s favorite killing device—a poisoned glass of buttermilk—was as American as could be.

Then there was Herman Drenth, who dispatched an indeterminate number of victims in his homemade gas chamber outside Clarksburg, West Virginia. He was hanged for five murders in 1932. Unlike most Bluebeards, Drenth was an admitted sadist, deriving not only financial profit but also sexual pleasure from his crimes. Watching his victims die, he told police, “Beat any cathouse I was ever in.”

“I may be a bit peculiar.”

G

EORGE

J

OSEPH

S

MITH

,

the “Brides in the Bath” murderer

B

OARD

G

AMES

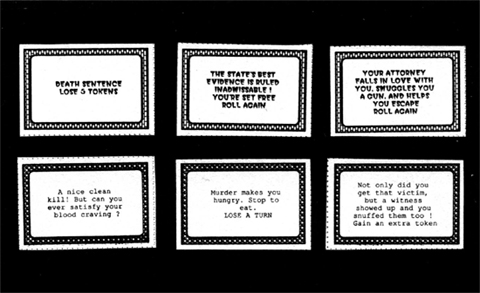

Though it seemed unlikely to become the next Trivial Pursuit, a board game called Serial Killer set off a firestorm of outrage when it was put on the market a few years ago. The brainchild of a Seattle child-care worker named Tobias Allen, Serial Killer consisted of a game board printed with a map of the United States, four serial-killer playing pieces, “crime cards,” “outcome cards,” and two dozen plastic “victims” (in the possibly ill-advised form of dead babies).

With the roll of a die, each player would move along the map and draw a crime card. Each card would involve either a “high-risk” or a “low-risk” crime, and the player would collect victims accordingly. As Allen explained, “A high-risk crime might be breaking into the house of a prominent citizen and killing him. A low-risk crime would be murdering a prostitute or a street person. Whoever has the highest body count at the end of the game wins.”

Game cards from Serial Killer board game

(Courtesy of Tobias Allen)

Though Allen intended the game as “a bit of a spoof on the way we glorify mass destruction,” many people failed to see the humor. A number of Canadian politicians mobilized to ban the game’s sale in their country. The fact that it came packaged in a plastic body bag apparently didn’t help.

“A quiet dorm could turn into a house of horrors when you visit! This campus is crawling with cops, though—so beware!”

Crime card from Serial Killer board game

B

ODY

P

ARTS

See

Trophies

.

BTK

The insatiable urge to kill is not a passing fancy. On the contrary, it is more like an addiction. And for serial murderers, like heroin junkies, it is very hard, if not impossible, to kick the habit.

True, there have been rare occasions when a string of savage murders comes to a sudden, mysterious halt: the Jack the Ripper case, for example, or the original Zodiac killings. Few experts believe, however, that those two psychopaths simply decided to quit committing random murder and return to their day jobs. It is far more likely that they were either locked away on some unrelated charge or died, either of natural causes or by suicide.

There’s an exception to every rule, however, as the case of the so-called BTK murders proves. Twenty-eight years after that madman’s last reported homicide, police finally arrested a suspect. His name was Dennis Rader, a colorless bureaucrat who—after allegedly terrorizing the city of Wichita, Kansas, in the 1970s with a series of horrific murders—somehow managed to set his homicidal impulses aside and retreat into a life of bland Midwestern normality.

The nightmarish case began in January 1974, when the killer murdered a husband and wife and two of their children. He went on to kill three more people, all young women, over the next three years. All the victims were bound and strangled and forced to endure prolonged suffering. As the murderer explained in one of the anonymous letters he sent to the media, his method was “Bind them, Torture them, Kill them.” He also supplied his own catchy moniker, as if to make it easier for the media to promote him. Using the acronym for his murder method, he called himself the “BTK Strangler.”

Always a hog for attention, the killer could get a bit peevish if he didn’t receive the response he thought he deserved. Once, he stewed for a week

waiting for a newspaper to acknowledge his note, then wrote a TV station to complain: “How many do I have to kill before I get my name in the paper or some national attention?”

While all this was going on, Dennis Rader was working in his quiet, fussy way, first at a residential security system company, then as a municipal codes enforcer who harried citizens for failing to leash their dogs or for letting their grass grow too high (see

Civil Servants

). In his spare time, he volunteered at his local Lutheran church and led a Boy Scout troop. As a troop leader, the alleged binder and torturer was especially keen on teaching boys how to tie a proper knot.

After the BTK murders seemed to stop at the end of 1977, experts like legendary FBI profiler Robert Ressler concluded that the culprit was out of commission in some way. Events of 2004 proved that, in the BTK case at least, this bit of conventional wisdom did not apply.