The Annals of Unsolved Crime (7 page)

Read The Annals of Unsolved Crime Online

Authors: Edward Jay Epstein

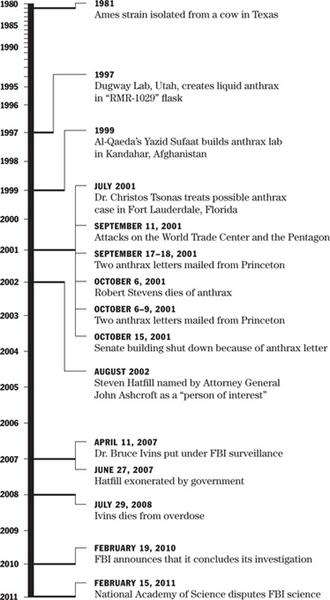

In late 2007, Ivins was harshly interrogated. By this time almost everything he had, including his home, computer, car, and personal effects were searched. Yet no trace of anthrax was found on any of his personal effects. His twin children were then offered a $2.5 million reward to provide evidence against their father, but they did not provide any. Meanwhile, his security clearance was withdrawn, barring him from his work. Even though he had passed his polygraph exam, the intensive searches produced no evidence that he had ever handled anthrax outside his lab or had driven to the Princeton-Trenton area in September 2001, and the FBI came up with no evidence linking him to the killer anthrax. However, the FBI found creepy behavior in Ivins’ personal life. He collected pornography, had web aliases, and admitted that he had become obsessed with a sorority girl. As the pressure continued, and his legal fees threatened to bankrupt him, he drank heavily, took prescription mind-altering drugs, acted erratically, and had a psychiatric breakdown. Finally, his life a shambles, on July 29, 2008, he killed himself with a Tylenol overdose. Though he was never charged or brought before a grand jury, the FBI identified him as the anthrax killer.

Less than a week after Ivins’ apparent suicide, the FBI declared him to have been the sole perpetrator of the 2001 anthrax attacks and released bizarre emails that he had written which, though unrelated to anthrax, suggested that he was a disturbed individual. Even though Ivins had not been indicted, and none of the case against him had ever been tested in a legal process, the FBI justified its extraordinary finding of guilt on the basis of the scientific evidence, which, it suggested before Congress, proved that Ivins, and Ivins alone, was behind the anthrax attack.

I had been investigating this case for seven years at this point, and I had interviewed scientists with whom Ivins had worked or who were otherwise familiar with his lab work. All of them told me that they did not believe that Ivins had the means to grow and then convert the liquid lab anthrax into the powdered attack anthrax without others in the lab observing this process. Jeffrey Adamovicz, one of the lab scientists I interviewed, wrote me: “Even if Bruce (or anyone else) wanted to use the fermentor in our labs, [and it] was non-operational, this person would have been observed even if it were operational.” I also found out that the FBI had never reverse-engineered or otherwise replicated the process by which the anthrax was produced. Indeed, almost all the attempts failed to reproduce the silicon content found in the anthrax in the letter sent to the

New York Post

. After I reported this FBI failure in a commentary in the

Wall Street Journal

on January 25, 2010, D. Christian Hassell, assistant director of the FBI Laboratory, replied to the

Wall Street Journal

, “The FBI is confident in the scientific findings that were reached in this investigation. We utilized established biological and chemical analysis techniques and applied them in an innovative manner to reach these findings.” But had the science actually validated the FBI’s conclusions?

To validate the science that the FBI had used to narrow the search to Ivins, the FBI contracted with the prestigious National Academy of Sciences (NAS) to conduct an independent assessment of its methods. The NAS took until February to complete its assignment. The result was not what the FBI expected. The NAS report concluded that the FBI’s key assertion that its genetic fingerprinting showed that the killer anthrax could only have come from the flask in Ivins’ custody was flawed. “The scientific data alone do not support the strength of the government’s repeated assertions that RMR-1029 was conclusively identified as the parent material to the anthrax powder used in the mailings,” it stated. “It is not possible to reach a definitive conclusion about the origins of the B. anthracis in the mailings based on the available scientific evidence alone.” Without a valid scientific basis for tracing the killer anthrax to Ivins’ lab, the FBI case against him is based on inference from his suspicious behavior.

The NAS report also raised questions as to where the anthrax was stolen from and where it was processed into powder. It revealed that the killer anthrax in the

New York Post

letter had a silicon content of “10 percent by mass.” Ivins’ lab anthrax had no silicon. The FBI had suggested that the silicon could have come naturally from the mixture of water and nutrients in which the anthrax was grown. But when the FBI attempted to test this theory by having the Lawrence Livermore National Lab grow anthrax in broth laced with silicon, it failed to match

the silicon signature. Out of fifty-six tries, most results were a whole order of magnitude lower, with some as low as .001 percent. The FBI had other labs attempts to reverse-engineer the killer anthrax, but the closest it came to the silicon signature was in some results from Dugway Proving Ground.

Ivins could still have committed the crimes, but he would have needed a collaborator at Dugway or elsewhere who had access to the powdered anthrax or the process to make it. This complication led Senator Leahy to tell FBI Director Robert Mueller, “I do not believe in any way, shape, or manner that [Ivins] is the only person involved in this attack on Congress.” Although the FBI did not agree, the case remains unsolved a decade later.

There remain a number of viable theories of the case. The FBI’s theory is that Ivins, and Dr. Ivins alone, was behind the attack. Senator Leahy’s theory is that Dr. Ivins may have been guilty, but that he could not have acted alone. Finally, there is the theory that a terrorist or foreign intelligence service was behind the attack. The NAS report found that, though the results were inconsistent, some samples collected abroad from an unnamed location possibly matched the attack anthrax.

My assessment is that the FBI failed to find the perpetrator of the anthrax attack. Indeed, it failed twice. Its first wrong man was Dr. Steven J. Hatfill, whose career was ruined by its 24/7 investigation of him; the second wrong man was Dr. Bruce Ivins, who committed suicide under its relentless pressure. In a case such as the anthrax attack, in which the weapon leaves microscopic traces everywhere, the equivalent of Sherlock Holmes’ dog-that-did-not-bark is the conspicuous absence of evidence. The FBI investigation was possibly the most massive in history in terms of expended man-hours. Consider then what evidence the FBI did not find that would have implicated their final suspect, Dr. Ivins.

First, no traces of anthrax were found in Ivins’ home, car,

clothing, garbage, or personal effects, so there is no evidence that Ivins ever removed anthrax from his lab.

Second, none of the dozens of scientists, technicians, and security guards that worked or visited Ivins’ lab, and were relentlessly interviewed by the FBI, ever witnessed him with the apparatus or growing vats necessary to process liquid anthrax (which was stored in a lab flask) into the powdered anthrax used in the attack. Yet to grow and dry this attack anthrax required gallons of media, as well as drying equipment such as a fermentor, which, according to other scientists who worked with him (and whom I interviewed), were not available to Ivins.

Third, the FBI was not able to find tollbooth records, gas purchases, or surveillance-camera evidence that Ivins drove his car to Princeton, or was in Princeton, during the period when the anthrax letters were mailed. If he was there, no one saw him, and he did not leave a trace of his presence.

Finally, the FBI could not trace the copies of the anthrax letters to any photocopying machine available to Ivins (or any other scientist at Fort Detrick). Nor could it find any pre-paid envelopes in Ivins’ home that matched those in which the anthrax letters were mailed. In short, there is no physical evidence actually linking Ivins to the anthrax attack.

Since the science by which the FBI attempted to eliminate all other suspects also turned out to be flawed, according to the exhaustive review by the National Academy of Science panel, it is not certain that the attack anthrax originated at the Fort Detrick lab. It could just as likely have come from the Battelle Memorial Lab in Ohio or the Army’s Dugway Proving Ground in Utah. In fact, the silicon signature in the anthrax points directly to Dugway. The Dugway lab had been making dry anthrax there, using the same strain of anthrax, since the late 1990s to test anthrax-detection devices. The concern here was that Iraq would use anthrax against U.S. forces, so Dugway scientists employed a multi-stage process to mill test anthrax

using a silica-based flow enhancer that was not available at Ivins’ facility at Fort Detrick. As there had been a number of security breaches at Dugway during this period, it is plausible that someone at Dugway stole a minute ampule of anthrax anytime after 1997 and, like any classic espionage operation, delivered it to another party, either foreign or domestic, who used it in the September 2001 attacks.

The lesson to be taken away from this unresolved crime is the vulnerability of even the most massive investigations to a preconception embedded in a behavioral profile. Just weeks after the attack, the FBI had arrived at a “behavioral assessment” pointing to a lone American scientist. It described, as David Willman reports in his 2011 book

Mirage Man

, a well-educated “single person” with “legitimate access to select biological agents,” who is “stand-offish,” and who prefers not to work in a “group team setting.” It was this assessment that steered the FBI first to Hatfield and then to Ivins. When the FBI’s behavioral science unit was created in 1972, its primary mission was profiling unknown serial killers by using historical data. But in the case of the anthrax attack, there was only one prior case of bioterrorism in the United States, the deliberate contamination with salmonella of salad bars in ten restaurants in Oregon. But this biological attack, which resulted in the poisoning of 751 individuals, was not perpetrated by a lone American. It was the act of a conspiracy in which the main perpetrators were foreign-born followers of the Indian spiritualist Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. Nor did the text of the anthrax letters themselves point to a single American scientist, since it used the plural “we,” contained the misspelling of the word “penicillin,” and also had jihadist formulations, such as “Death to America.” If, as the FBI assumed, the text was a deliberate deception, it left little material to support its profile of a lone American scientist. Yet, by clinging to this profile, it neglected investigative paths that may have resolved this crime.

CHAPTER 6

THE POPE’S ASSASSIN

On May 13, 1981, Mehmet Ali Agca, a twenty-three-year-old Turkish citizen, who was amidst a throng of people in the piazza in front of St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City, suddenly raised a Browning semi-automatic pistol, and shot Pope John Paul II no fewer than four times. The fusillade of bullets gravely wounded the pope, who survived the attack. Agca was captured gun in hand at the scene by Vatican security and Italian police. He had arrived in Rome by train only three days earlier. Under interrogation, Agca freely admitted firing the shots and said that he acted alone. Two years earlier, Agca had been sent to prison in Turkey for assassinating Abdi Ipekci, the editor of the newspaper

Milliyet

, a crime he confessed to on Turkish television. He had also threatened in a letter to kill Pope John Paul II, whom he called “the Commander of the Crusades” against Islam. He escaped from prison in November 1979. Based on his confession, the Italian investigation concluded that he acted as a lone fanatic when he shot the pope. In July 1981, he was tried in Rome, convicted, and sentenced to life imprisonment. Even with the conviction, it was not a closed case.

Within months, the case was transformed from a lone-assassin scenario to a possible conspiracy. The driving force for this new narrative was investigative journalism. In Turkey, journalist Ugur Mumcu was able to piece together an intriguing trail for Agca. It began with his well-planned escaped from a high-security Turkish prison in 1979, an escape in which

he walked out disguised as a soldier, and it continued as he assumed various other aliases, assisted by false travel documents through a half-dozen countries, including Bulgaria, Germany, Syria, and Iran, to Italy. According to Mumcu’s research, the jailbreak was organized by a Turkish terrorist organization called “The Grey Wolves,” which also supplied him with money, weapons, and documents. Meanwhile, in America, two separate journalistic investigations—one for the

Reader’s Digest

by Paul Henze, the CIA station chief in Turkey from 1974 to 1977; the other by Claire Sterling, who had written

The Terror Network

—uncovered evidence suggesting that Agca had been working for the Bulgarian intelligence service at the time of the assassination attempt. They also named a number of Bulgarian officials in Rome who they said may have been involved in the plot. As the firestorm grew in the Italian media, Agca was re-interrogated in prison. After being shown pictures of the Bulgarian officials in Italy, Agca changed his story. He now said he had two Bulgarian accomplices in Rome. He said one of them was Sergei Antonov, the representative in Rome of Balkan Air, the Bulgarian national airline, who drove him to St. Peter’s Square to shoot the pope. Antonov denied knowing Agca and having any involvement in the plot. Nevertheless, he was arrested by Italian authorities and put on trial for complicity in the attempt to kill the pope. During the trial, which extended over two years, Agca again changed his story, exonerating Antonov in rambling and incoherent testimony. Antonov was acquitted in 1986, returned to Bulgaria, became the subject of a novel called

The Executioner

by Stefan Kisyov, and died in 2007. His lengthy trial produced no evidence to substantiate the media stories that Agca was paid by the Bulgarian intelligence. For his part, Agca had made so many contradictory claims in the trial that his testimony was of little value in resolving the question of conspiracy. After the pope recovered and asked that Agca be shown mercy, Agca was extradited to

Turkey, and then, after twenty-eight years in prison, was released on January 18, 2010.