Authors: Brett McKay

The Art of Manliness - Manvotionals: Timeless Wisdom and Advice on Living the 7 Manly Virtues (14 page)

In one of his fiercest battles, it is known that Philip, King of Macedon, lost his eye from a bowshot. And when the soldiers picked up the shaft which wounded him, they perceived upon it these words: “To Philip’s eye!” The archer was so certain of his skill that he had announced his aim beforehand. It is a pitiable mistake, when one comes to care, like a lawn sportsman, more for a stately posture and a graceful attitude than for the mark he aims at.

Once when the British Science Association met in Dublin, Mr. Huxley arrived late at the city. Fearing to miss the president’s address he hurried from the train, jumped into a jaunting-car and breathlessly said to the driver, “Drive fast, I am in a hurry!” The driver slashed his horse with his whip and went spinning down the street. Suddenly it occurred to Mr. Huxley that he had probably not instructed the driver properly. He shouted to the driver, “Do you know where I want to go?” “No, yer ’onor,” was Pat’s laughing reply, “but I’m driving fast all the while.” There are many people who go through the world in this way. They are always going, and sometimes at great speed, but never get anywhere. They have no definite purpose and never accomplish anything.

It is the man that has an aim that accomplishes something in this world. A young man fired with a determined purpose to win in a particular aim has fought half the battle. What was it that has made men great in the past? One dominant aim! Names of great men at once suggest their life purpose. No one thinks of a Watt aside from the steam engine, a Howe suggests the sewing machine, a Bell the telephone, an Edison the electric light, a Morse the telegraph, a Cyrus Field the Atlantic cable. A man of one talent, fixed on a definite object, accomplishes more than a man of ten talents who spreads himself over a large surface. To keep your gun from scattering, put in a single shot.

“The idle pass through life leaving as little trace of their existence as foam upon the water or smoke upon the air; whereas the industrious stamp their character upon their age, and influence not only their own but all succeeding generations.” —Samuel Smiles

F

ROM

T

HE

S

TRENUOUS

L

IFE:

E

SSAYS AND

A

DDRESSES

, 1902

By Theodore Roosevelt

I wish to preach, not the doctrine of ignoble ease, but the doctrine of the strenuous life, the life of toil and effort, of labor and strife; to preach that highest form of success which comes, not to the man who desires mere easy peace, but to the man who does not shrink from danger, from hardship, or from bitter toil, and who out of these wins the splendid ultimate triumph.

A life of slothful ease, a life of that peace which springs merely from lack either of desire or of power to strive after great things, is as little worthy of a nation as of an individual. I ask only that what every self-respecting American demands from himself and from his sons shall be demanded of the American nation as a whole. Who among you would teach your boys that ease, that peace, is to be the first consideration in their eyes—to be the ultimate goal after which they strive? You men of Chicago have made this city great, you men of Illinois have done your share, and more than your share, in making America great, because you neither preach nor practise such a doctrine. You work yourselves, and you bring up your sons to work. If you are rich and are worth your salt, you will teach your sons that though they may have leisure, it is not to be spent in idleness; for wisely used leisure merely means that those who possess it, being free from the necessity of working for their livelihood, are all the more bound to carry on some kind of non-remunerative work in science, in letters, in art, in exploration, in historical research—work of the type we most need in this country, the successful carrying out of which reflects most honor upon the nation. We do not admire the man of timid peace. We admire the man who embodies victorious effort; the man who never wrongs his neighbor, who is prompt to help a friend, but who has those virile qualities necessary to win in the stern strife of actual life. It is hard to fail, but it is worse never to have tried to succeed. In this life we get nothing save by effort.

By John James Ingalls

Written by John James Ingalls (1833–1900), a U.S. Senator from Kansas, this poem was said to be Theodore Roosevelt’s favorite; when he was president, an autographed copy of the poem was the only thing besides a portrait to hang in his executive office in the White House.

Master of human destinies am I;

Fame, love, and fortune on my footsteps wait.

Cities and fields I walk; I penetrate

Deserts and seas remote, and passing by

Hovel and mart and palace—soon or late

I knock unbidden once at every gate!

If sleeping, wake—if feasting, rise before

I turn away. It is the hour of fate,

And they who follow me reach every state

Mortals desire, and conquer every foe

Save death; but those who doubt or hesitate

Condemned to failure, penury, and woe,

Seek me in vain, and uselessly implore.

I answer not, and I return no more!

Master of human destinies am I;

Fame, love, and fortune on my footsteps wait.

Cities and fields I walk; I penetrate

Deserts and seas remote, and passing by

Hovel and mart and palace—soon or late

I knock unbidden once at every gate!

If sleeping, wake—if feasting, rise before

I turn away. It is the hour of fate,

And they who follow me reach every state

Mortals desire, and conquer every foe

Save death; but those who doubt or hesitate

Condemned to failure, penury, and woe,

Seek me in vain, and uselessly implore.

I answer not, and I return no more!

“Industry, thrift and self-control are not sought because they create wealth, but because they create character.” —Calvin Coolidge

F

ROM

M

ORAL

L

ETTERS TO

L

UCILIUS

, 65 A.D.

By Seneca

The Roman Stoic philosopher Seneca wrote letters to his friend Lucilius in which he espoused the tenets of a life aligned with Stoic ideals. These letters were compiled in Epistulae morales ad Lucilium (Moral Letters to Lucilius). In this letter, Seneca beseeches Lucilius to use his time wisely.

Continue to act thus, my dear Lucilius—set yourself free for your own sake; gather and save your time, which ’til lately has been forced from you, or filched away, or has merely slipped from your hands. Make yourself believe the truth of my words—that certain moments are torn from us, that some are gently removed, and that others glide beyond our reach. The most disgraceful kind of loss, however, is that due to carelessness. Furthermore, if you will pay close heed to the problem, you will find that the largest portion of our life passes while we are doing ill, a goodly share while we are doing nothing, and the whole while we are doing that which is not to the purpose. What man can you show me who places any value on his time, who reckons the worth of each day, who understands that he is dying daily? For we are mistaken when we look forward to death; the major portion of death has already passed. Whatever years be behind us are in death’s hands.

Therefore, Lucilius, do as you write me that you are doing: hold every hour in your grasp. Lay hold of to-day’s task, and you will not need to depend so much upon to-morrow’s. While we are postponing, life speeds by. Nothing, Lucilius, is ours, except time. We were entrusted by nature with the ownership of this single thing, so fleeting and slippery that anyone who will can oust us from possession. What fools these mortals be! They allow the cheapest and most useless things, which can easily be replaced, to be charged in the reckoning, after they have acquired them; but they never regard themselves as in debt when they have received some of that precious commodity—time! And yet time is the one loan which even a grateful recipient cannot repay.

“Nihil sine labor.” (“Nothing without labor.”) —Latin maxim

Early to bed and early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy and wise.

Diligence is the mother of good luck.

God helps them that help themselves.

At the working man’s house hunger looks in, but dares not enter.

For industry pays debts, while despair increaseth them.

By diligence and patience the mouse ate in two the cable.

Little strokes fell great oaks.

Since thou art not sure of a minute, throw not away an hour.

Trouble springs from idleness, and grievous toil from needless ease.

Many, without labor, would live by their wits only, but they break for want of stock.

Sloth makes all things difficult, but industry all things easy.

Dost thou love life? Then do not squander time, for that is the stuff life is made of.

Sloth, like rust, consumes faster than labor wears, while the used key is always bright.

There will be sleeping enough in the grave.

Lost time is never found again.

Laziness travels so slowly, that Poverty soon overtakes him.

Industry need not wish, and he that lives upon hopes will die fasting.

Plough deep, while sluggards sleep.

Handle your tools without mittens; the cat in gloves catches no mice.

Constant dropping wears away stones.

A ploughman on his legs is higher than a gentleman on his knees.

“The chiefest action for a man of great spirit is never to be out of action … the soul was never put into the body to stand still.” —John Webster

F

ROM

T

HE

M

EMORABILIA

By Xenophon, c. 371 B.C.

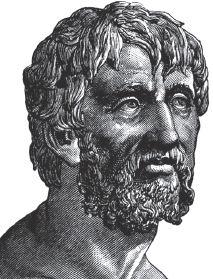

Xenophon (430–354 B.C. ) was an ancient Greek historian and student of the philosopher Socrates. His

Memorabilia

is a collection of Socratic dialogues which purports to record the defense Socrates made for himself during his trial before the Athenians. While arguing against indolence and for the beneficial effects of labor, Socrates cites a story told by the Sophist Prodicus: The Choice of Hercules.

This story was popular throughout the eighteenth century; John Adams used it to guide his life and wished to make an illustration of the tale the design for the Great Seal of the new nation. It is a fable used to convey a profound truth: that there can be no sweet without the bitter, no growth and no true happiness without work.