The Articulate Mammal (22 page)

Read The Articulate Mammal Online

Authors: Jean Aitchison

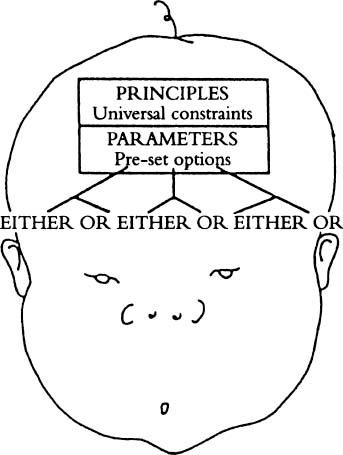

We were therefore dealing with ‘a system of unifying principles that is fairly rich in deductive structure but with parameters to be fixed by experience’ (Chomsky 1980: 66). The interlocking nature of the system would ensure that minor alterations would have multiple consequences: ‘In a tightly integrated theory with a fairly rich internal structure, change in a single parameter may have complex effects, with proliferating consequences in various parts of the grammar’ (Chomsky 1981: 6). In particular, ‘a few

changes in parameters yield typologically different languages’ (Chomsky 1986: 152). This whole idea has become known as the ‘principles and parameters’ or ‘P and P’ approach.

Once the values of the parameters are set, ‘the whole system is operative’ (Chomsky 1986: 146), and a child has acquired its

core language

. Only minor peripheral elements now remain to be learned:

Suppose we distinguish

core language

from

periphery

, where a core language is a system determined by fixing values for the parameters of UG, and the periphery is whatever is added on in the system actually represented in the mind/brain of a speaker-hearer.

(Chomsky 1986: 147)

In this system ‘what we “know innately” are the principles of the various subsystems … and the manner of their interaction, and the parameters associated with these principles. What we learn are the values of the parameters and the elements of the periphery’ (Chomsky 1986: 150).

Children had relatively little to do in this type of system: ‘We view the problem of language acquisition as … one of fixing parameters in a largely determined system’ (Chomsky 1986: 151). Indeed, many of the old rules which children had to learn just appeared automatically, because the principles underlying them were there already. Take the ‘rule’ that objects follow verbs, as in THROW THE BALL, EAT YOUR CAKE. The child might ‘know’ that languages behave consistently as far as heads and modifiers are concerned (as discussed above). Once the ‘head’ parameter is set, then the rule appears without any tedious learning, as does the rule that prepositions precede nouns, as in IN THE BATH, ON THE TABLE. As Chomsky noted: ‘There has been a gradual shift of focus from the study of rule systems … to the study of systems of principles, which appear to occupy a much more central position in determining the character and variety of possible human languages’ (Chomsky 1982: 7–8). If this minimal effort by the child is correct, then it makes sense to think of the language system as a ‘mental organ’, which grows mainly by itself, in the same way that the heart grows in the body. Chomsky became increasingly concerned with understanding the principles which underlay this growth.

PARING IT DOWN STILL FURTHER

Chomsky tried to become like a biologist who no longer looks in turn at a human heart, then at a human elbow, but instead aims to understand the body as a whole. Or, as he suggested, he was like someone trying to go beyond the simple observation that apples fall to the ground because that is

where apples inevitably end up, and instead, tries to understand the principle of gravity. In his words:

If we are satisfied that an apple falls to the ground because that is its natural place, there will be no serious science of mechanics. The same is true if one is satisfied with traditional rules for forming questions, or with the entries in the most elaborate dictionaries, none of which come close to describing simple properties of these linguistic objects.

(Chomksy 1995a: 387)

Increasingly, then, he tried to find the basic principles behind the tangled jungle of individual linguistic rules: ‘The task is to show that the apparent richness and diversity of linguistic phenomena is illusory … the result of interaction of fixed principles under slightly varying conditions’ (Chomsky 1995a: 389).

He therefore pared his proposals down to what he called a Minimalist Program, which contained hypotheses about the bare bones of language. This pared-down version retained basic switch-setting (p. 109), with its ‘principles’ and ‘parameters’, but two levels of structure were abolished. D-structure (once deep structure) and S-structure (once surface structure) no longer appeared as separate strata. The wordstore (lexicon) fed into a ‘computational system’, which checked that word combinations fitted in with basic principles. The wordstore also fed into a ‘spell-out’ which sifted through anything likely to affect the pronunciation. The endpoint was meaning on the one hand, and pronunciation on the other.

This bare-bones system remained in its preliminary stages. But the principles which guided the system were perhaps the most interesting part, though they remained sketchy. They were basically principles of ‘economy’ or simplicity. For example, one of these was ‘Shortest Move’. If one of two chunks of structure needed to be moved, then the one which moved least far must be selected. Take the sentence:

FENELLA PERSUADED ALPHONSE TO BUY A GREEN PARROT.

Suppose you wanted to check who was persuaded, and what was bought:

FENELLA PERSUADED WHO TO BUY WHAT?

Normally, any WH-word (word beginning with WH-such as WHO, WHAT) has to be brought to the front of the sentence. But only one can be moved. So here you have to choose. Should it be WHO or WHAT? Or doesn’t it matter? In fact, it matters very much. You can say:

WHO DID FENELLA PERSUADE TO BUY WHAT?

But not:

*WHAT DID FENELLA PERSUADE WHO TO BUY?

Only the WH-word nearest to the front can be moved, which ties in with Chomsky’s ‘Shortest Move’ principle.

This, then, was the type of principle which Chomsky hoped to identify – though his goal remained elusive. As he admitted:

Current formulation of such ideas still leaves substantial gaps. It is, furthermore, far from obvious that language should have anything like the character postulated in the minimalist program, which is just that: a research program concerned with filling the gaps and asking how positive an answer we can give to the question how ‘perfect’ is language?

(Chomsky 1995a: 390)

But if Chomsky is so unsure, does anybody else know? Chomsky’s increasingly broad and general claims about language brought him closer to people he originally disagreed with, those who argued that the broad general principles of language are indistinguishable from the broad general principles of human cognition in general. So where do we go from here?

Maybe the answer is to turn back from such huge abstract ideas, and to look again at the nitty-gritty of how humans actually use language. According to Michael Tomasello, ‘how children learn language is not a logical problem but an empirical problem.’ (Tomasello 2003: 328). In his opinion, we need to turn to a usage-based approach, one which explores how human children combine inherited talents and learned skills as they acquire language. He explains: ‘The human capacity for language is best seen as a conspiracy of many different cognitive, social-cognitive, information-processing, and learning skills, some of which humans share with primates and some of which are unique products of human evolution’ (Tomasello 2003: 321).

The next step is perhaps to look at child language, and see what can be gleaned from the way children learn to talk. This will be the topic of the next two chapters.

6

____________________________

CHATTERING CHILDREN

How do children get started on learning to speak?

They can’t talk straight

Any more than they can walk straight.

Their pronunciation is awful

And their grammar is flawful.

Ogden Nash,

It must be the milk

According to Ogden Nash, the behaviour of children and drunks is equally confusing. Linguists would perhaps agree with him. Listening to infants speaking is like being in topsy-turvy land. The problems of children faced with adult language sometimes seem trivial to a linguist who is trying to decipher infant burbles. But far worse than the problem of decipherment is the difficulty of interpreting the utterances. One writer remarked that writing about the acquisition of language:

is somewhat like the problem of reconstructing a dinosaur while the bones are still being excavated. It can happen that after you have connected what you earnestly believe are the hind legs you find that they are the jaw bones.

(McNeill 1970: vii)

Consequently, before we consider the main topic of this chapter – how children get started on learning to speak – we must outline some of the

problems of interpretation which arise when linguists attempt to analyse child language. We shall do this by considering one-word utterances.

BA, QUA, HA AND OTHER ONE-WORD UTTERANCES

One-word utterances present a microcosm of the difficulties faced by linguists examining child language. Consider the following situation. Suppose a child says BA when she is in the bath, again says BA when given a mug of milk, and also says BA to the kitchen taps. How are we to interpret this? There are at least four possible explanations.

The first possibility is that the child is simply naming the objects to prove she knows them, but has overgeneralized the word BA. That is, she has learnt the name BA for ‘bath’ and has wrongly assumed that it can apply to anything which contains liquid. A typical example of this type of overgeneralization was noted by one harassed mother in a letter to the London

Evening Standard

:

My baby is Moon-struck. She saw the moon in the sky at six o’clock last week and ever since she’s gaped at the sky shouting for the moon. Now she thinks anything that shines is the moon; street lamps, headlights, even the reflected light bulb in the window. All I hear is yells about the moon all day. I love my baby but I’m so ashamed. How does one get patience?

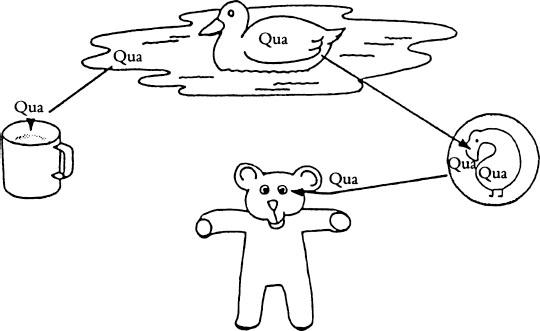

However, this plain overgeneralization interpretation may be too simple a view of what is happening when the child says BA. A second, and alternative, explanation has been proposed by the famous Russian psychologist Vygotsky (1893–1934). He suggested that when children overgeneralize they do so in a quite confusing way. They appear to focus attention on one aspect of an object at a time. One much quoted example concerns a child who used the word QUA to refer to a duck, milk, a coin and a teddy bear’s eye (Vygotsky 1962: 70). QUA ‘quack’ was, originally, a duck on a pond. Then the child incorporated the pond into the meaning, and by focusing attention on the liquid element, QUA was generalized to milk. But the duck was not forgotten, since QUA was used to refer to a coin with an eagle on it. Then, with the coin in mind, the child applied QUA to any round coin-like object, such as a teddy bear’s eye. Vygotsky called this phenomenon a ‘chain complex’ because a chain of items is formed, all linked by the same name. If he is correct, then in the case of BA, we can suggest that the child originally meant ‘bath’. Then, by focusing her attention on the liquid elements she generalized the word to ‘milk’. Meanwhile, remembering the bath taps, she used BA to mean ‘kitchen taps’ (see diagram on p. 102).

Yet even Vygotsky’s ‘chain complex’ interpretation seems oversimple in the view of some researchers. A third, and less obvious, point of view is that of

David McNeill, a psychologist at the University of Chicago. He argued that one-word utterances show a linguistic sophistication which goes far beyond the actual sound spoken. He claimed that the child is not merely involved in naming exercises, but is uttering

holophrases

, single words which stand for whole sentences. For example, BA might mean ‘I am in my bath’ or ‘Mummy’s fallen in the bath’. He justifies his viewpoint by claiming that misuse of words shows evidence of grammatical relationships which the child understands, but cannot yet express. For example, a 1-year-old child said HA when something hot was in front of her. A month later she said HA to an empty coffee cup and a turned-off stove. Why did she do this? McNeill suggested that:

by misusing the word the child showed that ‘hot’ was not merely the label of hot objects but was also something said of objects that could be hot. It asserted a property.

(McNeill 1970: 24)