The Articulate Mammal (26 page)

Read The Articulate Mammal Online

Authors: Jean Aitchison

And it is not only production of speech which fluctuates, but comprehension also. Richard Cromer tested children’s understanding of constructions such as THE WOLF IS TASTY TO BITE, THE WOLF IS HAPPY TO BITE, THE DUCK IS HORRIBLE TO BITE. Using glove puppets of a wolf and a duck, he asked the subjects to show him who was biting whom. To his surprise he concluded that ‘children may be very inconsistent in their answers from one day to the next’ (Cromer 1970: 405).

What causes this baffling inconsistency? There may be more than one reason. First, children make mistakes. Just as adults make grammatical errors such as DIDN’T YOU SAW BILL? instead of ‘Didn’t you see Bill?’ or ‘Didn’t you say you saw Bill?’, so do children. But this does not mean the utterances are random jumbles of words. The patterns are there, despite lapses. A second reason for inconsistency may be selective attention. Children may choose to concentrate on one aspect of speech at a time. If Sarah was working out rules for plurals one month, she may have ignored the -ING ending temporarily. As a schoolboy learning Latin said, ‘If I get the verb endings right, you can’t expect me to get the nouns right as well!’

However, mistakes and selective attention cannot account completely for the extreme fluctuations in Sarah’s use of -ING. Linguists have realized that inconsistency is a normal transitional stage as children move from one hypothesis to the next. It seems to occur when a child has realized that her ‘old’ pattern is wrong or partially wrong, and has formulated a new one, but remains confused as to the precise instances in which she should abandon her older primitive rule (Cromer 1970). For example, Cromer suggested that when they hear sentences such as THE DUCK IS READY TO BITE, children start out with a rule which says ‘The first noun in the sentence is doing the biting.’ As they get older, they become aware that this simple assumption does not always work. But they are not quite sure why or when their rule fails. So they experiment with a second rule, ‘Sometimes it is the first noun in the sentence which is doing the biting, but not always.’

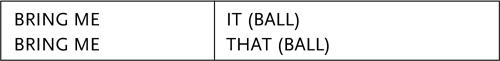

When a child has made an inference that is only partially right, he can get very bewildered. Partially correct rules often produce right results for the wrong reasons, as in sentences such as I DON’T WANT IT, where DON’T is treated as a single negative element. A further example of the confusion caused by a partially effective rule was seen in the Harvard child Adam’s use of the pronoun IT. He produced ‘odd’ sentences such as MUMMY GET IT LADDER, SAW IT BALL, alongside correct ones such as GET IT, PUT IT THERE. He appeared to be treating IT as parallel in behaviour to THAT which can occur either by itself, or attached to a noun: BRING ME THAT, BRING ME THAT BALL.

() Parentheses denote optional items.

But this was not the only wrong conclusion Adam reached. He also wrongly assumed that IT had an obligatory -S when it occurred at the beginning of a sentence, so he produced IT’S FELL, IT’S HAS WHEELS, as well as superficially correct utterances such as IT’S BIG. Presumably this error arose because Adam’s mother used a large number of sentences starting with IT’S …: IT’S RAINING, IT’S COLD and so on. When Adam’s ‘funny’ rules produced correct results half the time, it is not surprising that he took time to abandon them.

Perhaps the situation will become clearer if we look in detail at the emergence of one particular wrong word ending in the speech of one child. Consider the following utterances produced by a child named Sally when she was nearly 3:

ME MADEN THAT

ME TIPPEN THAT OVER

ME HADEN STAWBERRIES AT LUNCHTIME

ME JUST BUYEN IT

SOMETHING MAKEN A FUNNY NOISE.

Sally seemed to have decided that one way to deal with the past was to add -EN on to the ends of verbs. How did this strange personal ‘rule’ emerge? Did Sally just wake up one morning and start saying TIPPEN OVER, BUYEN, MADEN, or what happened? Fletcher (1983) examined Sally’s verbs ending in -EN in some detail (her progress was also recorded in Fletcher (1985), where she was called Sophie). He started recording her speech one November when she was almost 2½ years old. She began producing verbs ending in -EN in December. That month, there were three of them: BROKEN (which

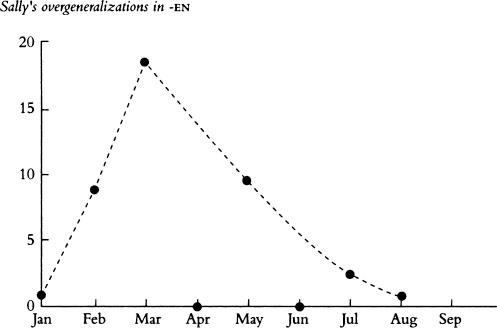

occurred thirteen times), then FALLEN (once) and TAKEN (once). Note that these three are all forms which actually occur in adult speech, even though Sally used them in her own idiosyncratic way, to denote a simple past tense. In the middle of January a new form, PUTTEN, emerged, alongside the existing three. This was the first non-existent form which she produced. In February, Sally used two more existing forms, GIVEN and EATEN, and eight more invented forms: BOUGHTEN, BUILDEN, RIDEN, GETTEN, CUTTEN, MADEN, WANTEN, TOUGHEN. The peak of Sally’s inventiveness came in March when she added on one actual word, WAKEN, and eighteen made-up ones: HADEN, STEPPEN, HURTEN, LEAVEN, BRINGEN, COMEN, DRAWNEN, HITTEN, LETTEN, RUNNEN, WASEN, SEE-EN, ROCKEN, HELPEN, SPOILEN, MAKEN, TIPPEN, HAVEN. In April, there were no new forms noted, but in May nine new invented ones appeared: LETTEN, WRAPPEN, SHOULDEN, HIDEN, WALKEN, BUYEN, CLOSEN, PLAYEN and a strange verb CAVEN, whatever Sally meant by that. In June the real form BITTEN was added. In July, a mere three invented forms emerged, WEAREN, LEAVEN, LIKEN, then in August just one, STAYEN. This was the last of the invented forms. Finally, an actual one, FORGOTTEN, appeared in December. The rise and fall of forms in -EN took just 9 months. This is represented on the graph below.

What can we learn from this? Of course, Sally’s speech was not recorded every moment of the day, so there may be some element of chance in the data. But she was probably recorded often enough (two or three times a week) for the sequence of events presented here to be reasonably reliable.

First, Sally seems to have picked out from adult speech several words ending in -EN which actually occur. She may well have heard them in sentences such as YOU’VE BROKEN IT, I’VE TAKEN YOUR DOLL upstairs, and

failing to take notice of the shortened form ‘VE (HAVE), she perhaps believed that she was dealing with a simple past tense – though this is speculation. What we

do

know is that she spent over a month using a small number of actual forms, and one in particular, BROKEN, which kept recurring. She then perhaps experimentally brought in a new one, PUTTEN. Her hypothesis that -EN was a correct ending was probably confirmed by hearing more actual -EN forms, since her next new form was GIVEN. She then became confident in her -EN endings, and had a surge of them in February and March. Soon after, she began to have doubts, and forms in -EN started to tail off, while Fletcher noted that her verbs ending in -ED were gradually increasing at this time, occurring in sentences such as:

ME CALLED IT PEANUT BUTTER.

SOME MILK DRIPPED, DROPPED ON THE FLOOR.

Eventually, the overgeneralized forms in -EN faded away completely. (Sally’s overall progress was discussed in Fletcher 1985.)

This scenario suggests that a new construction works its way into a child’s speech in a manner similar to that found in language change. In language change, first of all a few words get the new pronunciation, though not every time they occur. Then, when these few have acquired a firm hold, the change spreads rapidly to a large number of other words. Then finally, the change slowly rounds up the stragglers (Aitchison 2001). The word by word progress of a change through the vocabulary is known as

lexical diffusion

. In the case of Sally, the situation started off normally. The new ending got a firm footing in a few words, then spread rapidly to a large number. But as Sally had made a false hypothesis, the overgeneralized forms gradually decreased in number, then disappeared.

But how did Sally ever discover that her MAKEN, PUTTEN, BUILDEN forms were wrong? Children are not often receptive to correction, as we saw earlier (

Chapter 4

). So how do they discover their errors? This is a complex problem, which we shall return to in the next chapter. In this case, however, there may be a simple answer. Children seem to expect different words to mean different things, an expectation which has been called ‘the principle of contrast’ (Clark 1987). When she heard someone say, perhaps, DADDY BUILT THAT SNOWMAN, Sally may have realized that this was equivalent to her own DADDY BUILDEN THAT SNOWMAN. This may have led her to reassess her own ‘rule’, and eventually emend it.

We must conclude, then, that children are not just copying adult utterances when they speak. They seem to be following rules they devise themselves, and which produce systematic divergences from the adult output. Chomsky (1965) may have been partly on the right track in attributing to children an

innate hypothesis-forming device which enables them to form increasingly complex theories about the rules which underlie the patterns of the language they are exposed to. Like scientists, children are constantly testing new hypotheses. But, as we have seen, the scientist metaphor falls down in one vital respect. Scientists, once they have discarded a hypothesis, forget about it and concentrate on a new one. Children, on the other hand, appear to go through periods of experimentation and indecision in which two or more hypotheses overlap and fluctuate: each rule wavers for a long time, perhaps months, before it is finally adopted or finally abandoned.

Also, children’s hypotheses often apply only to rather small corners of language at a time. Occasionally one finds a broad sweeping ‘rule’ such as ‘Put NO in front of the sentence to negate it.’ But this type of across-the-board generalization is quite rare, and mostly children concentrate on much smaller pieces of structure. Language acquisition is turning out to be a much messier process than was once assumed.

One further point needs to be stressed. Children make the

right kind

of guesses about language. Their hypotheses are within a rather narrow range of possibilities. They are naturally equipped to have sensible linguistic hunches. This is a great feat, considering how baffled humans are by the vocal communication of other species:

There were three little owls in a wood,

Who sang hymns whenever they could.

What the words were about

One could never make out,

But one felt it was doing them good.

(Anon.)

Or, as a psychologist expressed human linguistic ability using somewhat more elegant phrases:

The fact that the brain can tolerate variation in language transmission and reception, despite different environmental inputs and still achieve the target capacity (being a native speaker of a natural language, perhaps several) provides support for a genetic component underlying language acquisition that is nevertheless biologically ‘flexible’ (neurologically plastic).

(Petitto 2005: 100)

We can now summarize the main conclusions of this chapter. In spite of difficulties connected with interpreting the data, we have come to some firm conclusions. Children automatically ‘know’ that language is patterned, and they seem to make a succession of hypotheses about the rules underlying the

speech they hear around them. However, these hypotheses overlap and fluctuate in a way that the hypotheses of scientists do not.

We also considered whether there is a universal framework underlying early speech. We noted that children everywhere seem to produce roughly comparable utterances at the two-word stage. However, it would be an exaggeration to claim that this represents a ‘universal framework’. All we can say is that children at this stage tend to express similar meaning relationships in a consistent way.

Therefore, in order to assess whether Chomsky was right in his assumption that children learning language make use of fairly specific outline facts which could be inbuilt, we must look in more detail at the way children cope with acquiring speech beyond the two-word stage. We also need to consider whether there are other plausible ways of explaining language development. This will be the topic of the next chapter.