The Articulate Mammal (32 page)

Read The Articulate Mammal Online

Authors: Jean Aitchison

We have now completed our discussion of language acquisition. But one point remains quite open. What kind of internal grammar does someone who has completed the acquisition of language have? In other words what does the internalized grammar of an adult look like? This is the next question to be considered. But before that, we have a brief excursus in which we discuss the following topic: how did Chomsky conceive the idea of a transformational grammar in the first place? And why has he, and most other linguists, changed his mind so much in recent years?

8

____________________________

CELESTIAL UNINTELLIGIBILITY

Why do linguists propose such bizarre grammars?

‘If any one of them can explain it,’ said Alice, ‘I’ll give him sixpence. I don’t believe there’s an atom of meaning in it.’

‘If there’s no meaning in it,’ said the King, ‘that saves a world of trouble, you know, as we needn’t try to find any. And yet I don’t know,’ he went on, ‘I seem to see some meaning after all.’

Lewis Carroll,

Alice in Wonderland

Linguists are sometimes accused of being ‘too abstract’ and ‘removed from reality’. For example, one reviewer has condemned ‘that celestial unintelligibility which is the element where the true student of linguistics normally floats and dances’ (Philip Toynbee,

The Observer

). Yet almost all linguists, not just psycholinguists, are trying to find out about a speaker’s mental ‘grammar’ – the internalized set of rules which enables someone to speak and understand their language. As Chomsky noted:

The linguist constructing a grammar of his language is in effect proposing a hypothesis concerning this internalized system.

(Chomsky 1972a: 26)

So the question which naturally arises is this: if linguists are really trying to form theories about an internalized system, why did Chomsky hit on something as complex and abstract as transformational grammar? Surely

there are other types of grammar which do not seem as odd? Some of the reasons for setting up a transformational grammar were mentioned in

Chapter 1

. But the question will be considered again from a different angle here, including some of the reasons why Chomsky has shifted his ideas so radically. Indeed, to some people Chomsky has played a ‘Duke of York’ trick on us all, as in the old nursery rhyme:

The grand old Duke of York,

He had ten thousand men,

He marched them up to the top of the hill,

Then he marched them down again.

Why did Chomsky march us to the top of the transformational hill, then march us all down again? And post-Chomsky, where is everybody trying to go now? Let’s start at the beginning.

JUPITER’S STICK INSECTS

Suppose … a spaceship full of English speakers had landed on Jupiter. They found the planet inhabited by a race of green stick insects who communicated by sitting down and wiggling their stick-like toes. The English speakers learned the Jupiter toe-wiggle language easily. It was a sign language like Washoe’s in which signs stood for words, with no obvious structure. So communication was not a serious problem. But the Emperor of Jupiter became highly envious of these foreigners who were able to walk about

and

communicate at the same time. They did not have to stop, sit down, and wiggle their toes. He decided to learn English.

At first, he assumed the task was easy. He ordered his servants to record all the sentences uttered by the English speakers, together with their meanings. Each morning he locked himself into his study and memorized the sentences recorded on the previous day. He carried out this routine unswervingly for about a year, dutifully learning every single sentence spoken by the foreigners. As he was an inhabitant of Jupiter, he had no natural ability for understanding the way a language worked. So he did not detect any patterns in the words, he simply memorized them. Eventually, he decided he knew enough to start testing his knowledge in conversation with the Englishmen.

But the result was a disaster. He didn’t seem to have learnt the sentences he needed to use. When he wanted to ask the Englishmen if they liked seaurchin soup, the nearest sentence he could remember having learnt was ‘This is funny-tasting soup. What kind is it?’ When it rained, and he wanted to

know if rain was likely to harm the foreigners, the most relevant sentence was ‘It’s raining, can we buy gumboots and umbrellas here?’

He began to have doubts about the task he had set himself of memorizing all English sentences. Would it ever come to an end? He understood that each sentence was composed of units called words, such as JAM, SIX, HELP, BUBBLE which kept recurring. But although he now recognized many of the words which cropped up, they kept appearing in new combinations, so the number of new sentences did not seem to be decreasing. Worse still, some of the sentences were extremely long. He recalled one in which an English speaker had been discussing a greedy boy: ‘Alexander ate ten sausages, four jam tarts, two bananas, a Swiss roll, seven meringues, fourteen oranges, eight pieces of toast, fourteen apples, two ice-creams, three trifles and then he was sick.’ The Emperor wondered despairingly what would have happened to the sentence if Alexander hadn’t been sick. Would it have gone on for ever? Another sentence worried him, which an English speaker had read out of a magazine. It was a summary of previous episodes in a serial story: ‘Virginia, who is employed as a governess at an old castle in Cornwall, falls in love with her employer’s son Charles who is himself in love with a local beauty queen called Linda who has eyes only for the fisherman’s nephew Philip who is obsessed with his half-sister Phyllis who loves the handsome young farmer Tom who cares only for his pigs.’ Presumably the writer ran out of characters to describe, the Emperor reasoned. Otherwise, the sentence could have gone on even further.

The Emperor had therefore deduced for himself two fundamental facts about language. There are a finite number of elements which can be combined in a mathematically enormous number of ways. And it is

in principle

impossible to memorize every sentence because there is no linguistic bound on the length of a sentence. Innumerable ‘sub’-sentences can be joined on to the original one, a process known as

conjoining

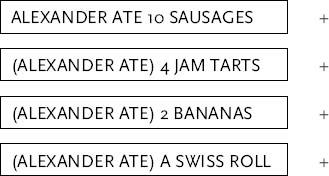

:

Alternatively, sub-sentences can be inserted or

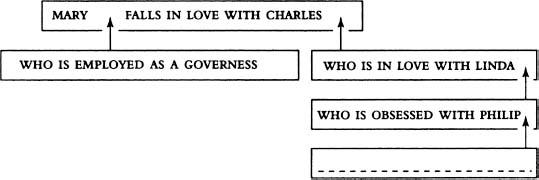

embedded

inside the original one:

This property of language is known as

recursiveness

from the Latin to ‘run through again’ – you can repeatedly apply the same rule to one sentence, a process which could (in theory) go on for ever. Of course, in practice you would fall asleep, or get bored or get a sore throat. But these are not

linguistic

reasons for stopping. This means that no definite set of utterances can ever be assembled for any language.

The Emperor of Jupiter eventually concluded that memorization of all English sentences was impossible. He realized it was the

patterns

behind the utterances which mattered.

How should he discover what these were? One way would be to make a list of all the English words he had collected, and to note whereabouts in the sentence each one occurred. He started to do this. But he hit on problems almost immediately. He had a feeling that some of his sentences had mistakes in them, but he was not sure which ones. Was ‘I hic have hic o dear hic hiccups’ a well-formed English sentence or not? And what about ‘I mean that what I wanted I think to say was this’?

His other problem was that he found gaps in the patterns, and he didn’t know which ones were accidental, and which not. For example, he found four sentences containing the word ELEPHANT:

THE ELEPHANT CARRIED TEN PEOPLE.

THE ELEPHANT SWALLOWED TEN BUNS.

THE ELEPHANT WEIGHED TEN TONS.

TEN PEOPLE WERE CARRIED BY THE ELEPHANT.

But he did not find:

TEN BUNS WERE SWALLOWED BY THE ELEPHANT.

TEN TONS WERE WEIGHED BY THE ELEPHANT.

Why not? Were these gaps accidental? Or were the sentences ungrammatical? The Emperor did not know, and grew very depressed. He had discovered another important fact about language: collections of utterances must be

treated with caution. They are full of false starts and slips of the tongue. And they constitute only a small subset of all possible utterances. In linguistic terms, a speaker’s

performance

or

E-language

(externalized language) is likely to be a random sample bespattered with errors, and does not necessarily provide a very good guide to his or her

competence

or

I-language

(internalized language), the internal set of rules which underlie them.

The Emperor of Jupiter realized that he needed the help of the foreigners themselves. He arrested the spaceship captain, a man called Noam, and told him that he would free him as soon as he had written down the rules of English. Noam plainly knew them, since he could talk.

Noam was astounded. He pleaded with the Emperor, pointing out that speaking a language was an ability like walking which involved knowing

how

to do something. Such knowledge was not necessarily conscious. He tried to explain that philosophers on earth made a distinction between two kinds of knowing: knowing

that

and knowing

how

. Noam knew

that

Jupiter was a planet, and factual knowledge of this type was conscious knowledge. On the other hand, he knew

how

to talk and

how

to walk, though he had no idea how to convey this knowledge to others, since he carried out the actions required without being aware of how he actually managed to do them.

But the Emperor was adamant. Noam would not be freed until he had written down an explicit set of rules, parallel to the system internalized in his head.

Noam pondered. Where could he begin? After much thought he made a list of all the English words he could think of, then fed them into a computer with the instructions that it could combine them in any way whatsoever. First it was to print out all the words one by one, then all possible combinations of two words, then three words, then four words, and so on. The computer began churning out the words as programmed, and spewed out (in the fourword cycle) sequences such as:

DOG INTO INTO OF

UP UP UP UP

GOLDFISH MAY EAT CATS

THE ELEPHANT LOVED BUNS

DOWN OVER FROM THE

SKYLARKS KISS SNAILS BADLY.

Sooner or later, Noam reasoned, the computer would produce every English sentence.

Noam announced to the Emperor that the computer was programmed with rules which made it potentially capable of producing all possible sentences of English. The Emperor was suspicious that the task had been completed so quickly. And when he checked with the other foreigners, his

fears were confirmed. The others pointed out the although Noam’s computer program could in theory generate

all

English sentences, it certainly did not generate

only

the sentences of English. Since the Emperor was looking for a device which paralleled a human’s internalized grammar, Noam’s programme must be rejected, because humans did not accept sentences such as: