The Articulate Mammal (35 page)

Read The Articulate Mammal Online

Authors: Jean Aitchison

If we persisted, and said, ‘What exactly do you mean by an indirect relationship?’ he would probably have said: ‘Look, please stop bothering me with silly questions. The relationship between language usage and language knowledge is not my concern. Let me put you straight. All normal people seem to have a tacit knowledge of their language. If that knowledge is there, it is my

duty as a linguist to describe it. But it is not my job to tell you how that knowledge is used. I leave that to the psychologists.’

This, to a psycholinguist, seemed an extremely unhappy state of affairs. She is just as much interested in language usage as language knowledge. In fact, she finds it quite odd that anybody is able to concentrate on one rather than the other of these factors, since they seem to her to go together rather closely. Consequently, in this chapter, we shall be briefly examining both Chomsky’s views and attempts made by psycholinguists to assess the relationship between a linguist’s grammar and the way someone produces and comprehends sentences.

LINGUISTIC KNOWLEDGE

Chomsky (1965) claimed that the grammar he proposed ‘expresses the speaker-hearer’s knowledge of the language’. This knowledge was latent or ‘tacit’, and ‘may well not be immediately available to the user of the language’ (Chomsky 1965: 21).

The notion of tacit or latent knowledge is a rather vague one, and may cover more than Chomsky intended. It seems to cover two types of knowledge. On the one hand, it consists of knowing

how

to produce and comprehend utterances. This involves using a rule system, but it does not necessarily involve any awareness of the rules – just as a spider can spin a web successfully without any awareness of the principles it is following. On the other hand, knowledge of a language also covers the ability to make various kinds of judgements about the language. The speaker not only knows the rules, but in addition, knows something about that knowledge. For example, speakers can quickly distinguish between well-formed and deviant sentences. An English-speaker would unhesitatingly accept:

HANK MUCH PREFERS CAVIARE TO SARDINES.

but would quickly reject:

*HANK CAVIARE TO SARDINES MUCH PREFERS.

In addition, mature speakers of a language can recognize sentence relatedness. They ‘know’ that a sentence:

FADING FLOWERS LOOK SAD.

is closely related to:

FLOWERS WHICH ARE FADING LOOK SAD.

and that:

IT ASTONISHED US THAT BUZZ SWALLOWED THE OCTOPUS WHOLE.

is related to:

THAT BUZZ SWALLOWED THE OCTOPUS WHOLE ASTONISHED US.

Moreover, they can distinguish between sentences which look superficially alike but in fact are quite different, as in:

EATING APPLES CAN BE GOOD FOR YOU.

(Is it good to eat a type of apple called an eating apple, or is any type of apple good to eat?), or:

SHOOTING STARS CAN BE FRIGHTENING.

SHOOTING BUFFALOES CAN BE FRIGHTENING.

(How do you know who is doing the shooting?)

There seems to be no doubt whatsoever that a ‘classic’ (1965) transformational grammar encapsulated this second type of knowledge, the speaker’s awareness of language structure. People

do

have intuitions or knowledge of the type specified above, and a transformational grammar did seem to describe this.

However, it is by no means clear how a ‘classic’ transformational grammar or the later ‘minimalist program’ related to the first type of knowledge – the knowledge of how to actually

use

language. Chomsky claimed that a speaker’s internal grammar has an important bearing on the production and comprehension of utterances, but he made it quite clear that this grammar ‘does not, in itself, prescribe the character or functioning of a perceptual model or a model of speech production’ (Chomsky 1965: 9). And at one point he even labelled as ‘absurd’ any attempt to link the grammar directly to processes of production and comprehension (Chomsky 1967: 399).

This viewpoint persisted in his later work, where he denied that knowledge had anything to do with ability to use a language: ‘Ability is one thing, knowledge something quite different’ (Chomsky 1986: 12), commenting that ‘we should follow normal usage in distinguishing clearly between knowledge and ability to use that knowledge’. And as we have seen, the type of knowledge outlined in his later theories is considerably more abstract and deep-seated than that involved in a ‘classic’ transformational grammar.

In short, Chomsky is interested primarily in ‘the system of knowledge that underlies the use and understanding of language’ rather than in ‘actual or potential behaviour’ (Chomsky 1986: 24).

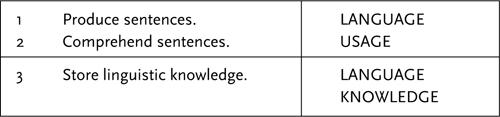

Let us put the matter in another way. Anyone who knows a language can do three things:

We are saying that Chomsky’s proposals seem undoubtedly to cover (3), but appear to be separate from, or only indirectly related to (1) and (2).

This is a rather puzzling state of affairs. Is it possible for linguistic knowledge to be completely separate from language usage? This is the topic of the rest of the chapter. We shall start by looking at the earliest psycholinguistic experiments on the topic, which were carried out in the early 1960s.

THE YEAR OF ILLUSION

When Chomsky’s ideas spread across into the field of psychology in the early 1960s they made an immediate impact. Psychologists at once started to test the relevance of a transformational grammar to the way we process sentences. Predictably, their first instinct was to test whether there was a direct relationship between the two.

At this time, two different but similar viewpoints were put forward. The first was a strong and fairly implausible theory, sometimes known as the ‘correspondence hypothesis’, and the second was a weaker and (slightly) more plausible idea known as the ‘derivational theory of complexity’ or DTC for short.

Supporters of the correspondence hypothesis postulated a close correspondence between the form of a transformational grammar, and the operations employed by someone when they produce or comprehend speech. Supposedly ‘the sequence of rules used in the grammatical derivation of a sentence … corresponds step by step to the sequence of psychological

processes that are executed when a person processes the sentence’ (Hayes 1970: 5). This was soon found to be unlikely.

Supporters of DTC put forward a weaker hypothesis. They suggested that the more complex the transformational derivation of a sentence – that is, the more transformations were involved – the more difficult it would be to produce or comprehend. They did not, however, assume a one-to-one correspondence between the speaker’s mental processes and grammatical operations.

A number of now famous experiments were devised to test these claims. Perhaps the best-known was a sentence-matching experiment by George Miller of Harvard University (Miller 1962; Miller and McKean 1964).

Miller reasoned that if the number of transformations significantly affected processing difficulty, then this difficulty should be measurable in terms of time. In other words, the more transformations a sentence had, the longer it should take to cope with. For example, a passive sentence such as:

THE OLD WOMAN WAS WARNED BY JOE.

should be harder to handle than a simple active affirmative declarative (or SAAD for short) such as:

JOE WARNED THE OLD WOMAN.

since the passive sentence required an additional transformation. However, this passive should be easier to handle than a passive negative such as:

THE OLD WOMAN WASN’T WARNED BY JOE.

which required one more transformation still.

In order to test this hypothesis, Miller gave his subjects two columns of jumbled sentences, and asked them to find pairs which went together. The sentences to be paired differed from one another in a specified way. For example, in one section of the experiment actives and passives were jumbled, so that a passive such as:

THE SMALL BOY WAS LIKED BY JANE.

had to be matched with its ‘partner’:

JANE LIKED THE SMALL BOY.

And:

JOE WARNED THE OLD WOMAN.

had to be paired with:

THE OLD WOMAN WAS WARNED BY JOE.

Miller assumed that the subjects had to strip the sentences of their transformations in order to match them up. The more they differed from each other, the longer the matching would take, he predicted.

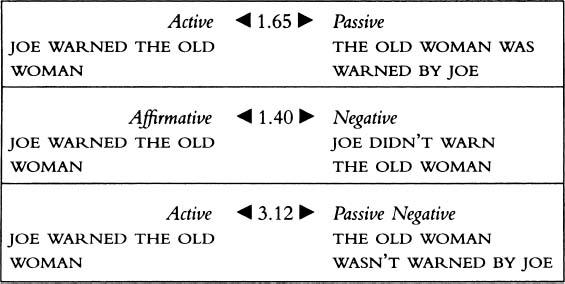

Miller carried out this experiment twice, the second time with strict electronic time-controls (a so-called ‘tachistoscopic’ method). His results delighted him. Just as he had hoped, it took nearly twice as long to match sentences which differed by

two

transformations as it took to match sentences which differed by only one transformation. When he added the time needed to match actives with passives (approximately 1.65 seconds) to the time taken to pair affirmatives with negatives(approximately 1.40 seconds), the total added up to almost the same as that required for matching active with passive negative sentences (approximately 3.12 seconds).

Miller seemed to have proved that transformations were ‘psychologically real’, since each transformation took up a measurable processing time.

But this period of illusion was shortlived. A time of disappointment and disillusion followed. Fodor and Garrett (1966) gave a crushing paper at the Edinburgh University conference on psycholinguistics in March 1966, in which they clearly showed the emptiness of the ‘correspondence hypothesis’ and DTC. They gave detailed theoretical reasons why hearers do not ‘unwind’ transformations when

they comprehend speech. For example, the correspondence hypothesis entailed the consequence that people do not begin to decode what they are hearing until a sentence was complete. It assumed that, after waiting until they had heard all of it, hearers then undressed the sentence transformation by transformation. But this was clearly wrong, it would take much too long. In fact, it can be shown that hearers start processing what they hear as soon as a speaker begins talking.

In addition, Fodor and Garrett pointed out flaws in the experiments carried out by Miller and others. The transformations, such as passive and negative, on which their results crucially depended, were atypical. Negatives changed the meaning, and passives moved the actor away from its normal place at the beginning of an English sentence. Passives and negatives are also longer than SAADs, so it was not surprising that they took longer to match and were more difficult to memorize. The difficulty of these sentences need not have anything to do with transformational complexity. Fodor and Garrett pointed out that some other transformations made no difference to processing difficulty. There was no detectable difference in the time taken to comprehend: