The Articulate Mammal (39 page)

Read The Articulate Mammal Online

Authors: Jean Aitchison

If these psychologists are correct in their claim, then sentences containing verbs which give no choice of construction should be easier to process than those which contain ‘versatile verbs’ – verbs associated with multiple constructions. In the case of a verb such as KICK, the hearer only has a simple lexical entry to check. But in the case of a verb such as EXPECT, they mentally activate each of the possible constructions before picking on the correct one. This suggestion was known as the ‘verbal complexity hypothesis’.

Several psycholinguists tried to test this theory, including Fodor, Garrett and Bever themselves. In one experiment, they gave undergraduates pairs of sentences which were identical except for the verb. A single-construction verb was placed in one sentence (e.g. MAIL), and a multiple-construction verb in the other (e.g. EXPECT):

THE LETTER WHICH THE SECRETARY MAILED WAS LATE.

THE LETTER WHICH THE SECRETARY EXPECTED WAS LATE.

They jumbled up the words in each, and then asked the students to unscramble them. They found what they had hoped to find – that it was much easier to sort out the single-construction verb sentences. But this experiment has been criticized. The problem is that it did not test comprehension directly: it assessed the difficulty of a task which occurred

after

the sentence had been originally processed.

Later researchers checked on the difficulty of versatile verbs via a lexical decision task – asking subjects to decide whether a sequence of letters such as DOG or GLIT flashed up on a screen is a word or not. Supposedly, reaction times to this task will be slower if the letter sequence is presented just after subjects have heard a versatile verb. One group of researchers who tried this did not find the predicted effect (Clifton

et al

. 1984). They concluded that hearers had no extra difficulty provided that the verb was followed by its preferred construction. For example, I THINK THAT … (e.g. I THINK THAT MAVIS IS A FOOL) would cause less trouble than I THINK AS … (e.g. I THINK AS I WALK TO WORK). In other words, hearers may activate in advance one favoured construction for a given verb, but there is no need for them to activate mentally all possible constructions associated with it. If only one favoured construction is activated per verb, then ‘versatile verbs’ are no more difficult to deal with than non-versatile ones, except when an odd or unexpected option is chosen.

This conclusion is supported by the work of some other researchers (e.g. Ford

et al

. 1982). Consider the sentence:

THE PERSON WHO COOKS DUCKS OUT OF WASHING THE DISHES.

At first, we expect the word DUCKS to be the object of the word COOKS. But since we need a main verb, we are forced to revise our interpretation to:

THE PERSON [WHO COOKS] DUCKS OUT OF WASHING THE DISHES.

Our knowledge of the verb COOKS led us astray, since it is often, though not necessarily, followed by the thing which is cooked.

However, another group of researchers

did

find that a versatile verb caused problems, though in a somewhat unexpected way. The number of different constructions following a verb did not matter particularly. Instead, difficulties arose with verbs where it was not immediately obvious who did what to whom (Shapiro

et al

. 1987). Consider the sentence:

SHELDON SENT DEBBIE THE LETTER.

This type of sentence took up extra processing time because people were not at first sure whether Debbie or something else was being sent.

On balance, versatile verbs do not cause the problems they were once expected to cause. Listeners may be mentally prepared for a variety of constructions, but this does not seem to delay processing, unless there is some additional difficulty, such as an unusual construction, or problems in deciding who did what to whom. Perhaps a hearer is like a car-driver, driving behind a bus. She has certain expectations about what the bus in front is likely to do. It can go straight on, turn left or turn right, and she is ready to respond appropriately to any of these. But she might be taken by surprise if the bus reversed. Similarly, perhaps versatile verbs are a problem only if they spring a surprise on the hearer.

INFORMED GUESSES

A key question which puzzled researchers for a number of years is whether listeners take a ‘top-down’ or ‘bottom-up’ approach when they process sentences. That is, do they impose their expectations on what they are hearing, and get puzzled if these expectations are not fulfilled? This is a top-down approach. On the other hand, do they listen to the words said to them, and then try to assemble them in some type of order? This is a bottom-up approach. As we learn more about the way human speech comprehension works, it now seems that both viewpoints combine together. But some of the earlier work on the subject explored a top-down approach, and this can still explain a lot about how humans understand chunks of words.

When someone hears a sentence, she often latches on to outline clues, and ‘jumps to conclusions’ about what she is hearing. An analogy might make this clearer. Suppose someone found a large foot sticking out from under her bed one night. She would be likely to shriek ‘There’s a man under my bed’, because past experience has led her to believe that large feet are usually attached to male human beings. Instead of just reporting the actual situation ‘There is a foot sticking out from under the bed’, she has jumped to the conclusion that this foot belongs to a man, and this man is lying under the bed.

The evidence suggests that we make similar ‘informed guesses’ about the material we hear. One of the first people to work on listeners’ expectations was Tom Bever, a psychologist at Columbia University, New York. The next few pages are based to a large extent on suggestions made by him.

Hearers approach the sentences of English with at least four basic assumptions, according to a key paper by Bever, published over a quarter of a century ago (1970). Guided by their expectations, they devise rules of thumb or ‘strategies’ for dealing with what they hear. Let us briefly consider these assumptions and linked strategies. Although we shall be labelling them ‘first’, ‘second’, ‘third’ and ‘fourth’, this is not meant to refer to the order in which they are used, since all four may be working simultaneously.

Assumption 1

‘Every sentence consists of one or more sentoids or sentencelike chunks, and each sentoid normally includes a noun-phrase followed by a verb, optionally followed by another noun-phrase.’ That is, every sentence will either be a simple one such as:

DO YOU LIKE CURRY?

TADPOLES TURN INTO FROGS.

DON’T TOUCH THAT WIRE.

or it will be a ‘complex’ one containing more than one sentence-like structure or sentoid. For example, the sentence:

IT IS NOT SURPRISING THAT THE FACT THAT PETER SINGS IN HIS BATH UPSETS THE LANDLADY.

contains three sentoids:

IT IS NOT SURPRISING

THAT THE FACT UPSETS THE LANDLADY

THAT PETER SINGS IN HIS BATH.

Within a sentence, each sentoid normally contains either a noun phrase–verb sequence such as:

THE LARGE GORILLA GROWLED.

or a noun phrase–verb–noun phrase sequence such as:

COWS CHEW THE CUD.

The strategy or working principle which follows from assumption 1 seems to be: ‘Divide each sentence up into sentoids by looking for noun phrase – verb (–noun phrase) sequences.’ This is sometimes referred to as the

canonical sentoid

strategy, since noun phrase–verb–noun phrase is the ‘canonical’ or standard form of an English sentence. It is clear that we need such a strategy when we distinguish sentoids, since there are often no acoustic clues to help us divide a sentence up (

Chapter 1

).

A clear confirmation of this strategy comes when people are presented with a sentence such as:

LLOYD KICKED THE BALL KICKED IT.

which was said in a football commentary. Most people deny that it is possible, claiming it must be:

LLOYD KICKED THE BALL THEN KICKED IT AGAIN.

But it is a well-formed English sentence, as shown by the similar one:

LLOYD THROWN THE BALL KICKED IT.

People just cannot think of the interpretation ‘to whom the ball was kicked’, the canonical sentoid strategy is too strong. And similar examples abound in the literature, perhaps the most famous being:

THE HORSE RACED PAST THE BARN FELL.

A common comment about this one is: ‘I can’t understand it because I don’t know the word BARNFELL.’ The alternative interpretation of RACED as ‘which was raced’ is rarely considered.

Further confirmation of this strategy comes from so-called ‘centre embeddings’ – sentences which have a Chinese box-like structure, one lying inside the other. The following is a double centre embedding – one sentence is inside another which is inside yet another.

(The man laughed: the girl believed the man; the boy met the girl.)

Blumenthal (1966) tested to see what happened when sentences of this type were memorized. He noted that subjects tended to recall them as noun–verb sequences:

THE MAN, THE GIRL AND THE BOY MET, BELIEVED AND LAUGHED.

Their immediate reaction to being presented with such an unusual sentence was to utilize the canonical sentoid strategy even though it was, strictly speaking, irrelevant. In a later experiment, Bever found to his surprise that subjects imposed an NP–V–NP sequence on sentences of this type

even after practice

. He comments, ‘the NVN sequence is so compelling that it may be described as a “linguistic illusion” which training cannot readily overcome’ (Bever 1970: 295).

The canonical sentoid strategy seems to start young. Bever noted that by around the age of 2, children are already looking out for noun–verb sequences – though they tend to assume that the first noun goes with the first verb, and interpret:

THE DOG THAT JUMPED FELL.

as:

THE DOG JUMPED.

Assumption 2

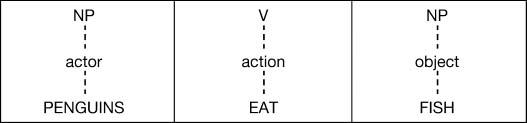

‘In a noun phrase–verb–noun phrase sequence, the first noun is usually the actor and the second the object.’ That is, an English sentence normally has the word order actor–action–object with the person doing the action coming first as in:

GIRAFFES EAT LEAVES.

DIOGENES BOUGHT A BARREL.

The strategy which stems from assumption 2, seems to be as follows: ‘Interpret an NP–V–NP sequence as actor – action – object unless you have strong indications to the contrary.’

A number of experiments have shown that sentences which do not have the actor first take longer to comprehend if there are no semantic clues. The best known of these may be Slobin’s ‘picture verification’ experiment (1966b). He showed subjects pictures, and also read them out a sentence. Then he timed how long it took them to say whether the two matched. He found that passives such as:

THE CAT WAS CHASED BY THE DOG.

took longer to verify than the corresponding active:

THE DOG CHASED THE CAT.

Another picture verification experiment showed that actor–action–object structures are comprehended more quickly than other structures which would fit the NP–V–NP sequence (Mehler and Carey 1968):