The Audacity of Hops: The History of America's Craft Beer Revolution (43 page)

Read The Audacity of Hops: The History of America's Craft Beer Revolution Online

Authors: Tom Acitelli

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

Sam Calagione, the cofounder of Dogfish Head.

COURTESY OF DOGFISH HEAD BREWERY

And Sam Calagione had ideas. He had, after all, learned a lot from his homework at the New York Public Library. He had declared to those assembled at his Manhattan apartment at the tail end of the tasting party for his homemade Cherry Brew that he would be a brewer. Now, barely three years later, in the summer of 1995, he was making good on that drunken boast as he and Mariah prepared to open the draft-only brewpub. He named it after a peninsula in Maine where he spent boyhood summers and picked Rehoboth Beach in southern Delaware because it was Mariah's hometown (the pair had been together since Calagione's rocky high school years). It did not hurt in terms of free publicity, Sam figured, that Delaware had no other craft breweries or brewpubs; in fact, he was to find out only after he leased space that, as in only seven others, brewpubs were still banned in the First State, something he personally lobbied to change.

The brewpub was off the beach's beaten path, a shell of a restaurant vacated so quickly that there were still liquor bottles on the shelves and a couple of onion rings in the fryer when Calagione walked through itânot to mention a few bras, some boxers, and a stiletto heel elsewhere inside. Its location earned him a break on the rent with an option to buy, a clause he sensed the owner included only because she didn't think his business would last. Had she known more about what kinds of beers Calagione planned to produce, the owner's hunch would have been all the more justified.

Calagione's research (Bill Owens's

How to Build a Small Brewery

became a bible) and his own familiarity with craft beers had convinced him that the vast majority were based on interpretations of European styles. He was correct. There were only two distinctly American styles of beer at that point: steam beer, which Anchor had an excusable monopoly on (not to mention a trademark), and cream ale, perhaps most famously interpreted by the regional Genesee Brewing Company based in Rochester, New York. The rest were spins on styles developed in Ireland, Scotland, England, Belgium, the Czech Republic, and especially Germany, with its long tradition of beers brewed under the Reinheitsgebot, the sixteenth-century Bavarian purity dictate that required beer be made only from water, barley, and hops (they didn't know about yeast's role). It no longer carried the weight of law, but its influence remained profound in Europe and the United States. Calagione saw an opening in this emphasis on European styles by Anchor, Sierra Nevada, Boston Beerâall the brands he was familiar with, admired, and liked to drink. They're doing those sorts of things really well, he thought. We're not going to stand out just trying to copy what they do.

Calagione's research into craft beer had taken him down other culinary avenues similar in approach and scope to what he had chosen to do, the sorts of avenues, like artisan breads and coffees, that would within a decade be associated with locavores and that were already linked with the nascent Slow Food movement. Artisan bread was then being called “the next food craze,” with upscale bakery-cafés peppering cities like Boston, San Francisco, Seattle, and New York; there were even chains, like Au Bon Pain and the St. Louis Bread Company (Au Bon Pain would absorb the St. Louis Bread Company in the mid-1990s, repositioning it as Panera Bread). Calagione saw in these other artisan foodstuffs an opportunity to embrace every ingredient under the sun in brewing. There would, of course, be water, yeast, and grain undergirding everything, with hops of different varieties, too. Otherwise, it was open season. It was a sort of Reinheitsgebot for Generation X on the cusp of the twenty-first century.

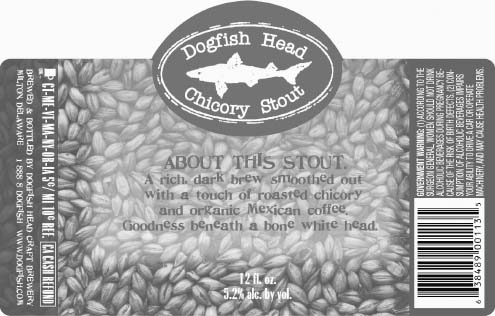

Dogfish Head's Chicory Stout.

When the brewpub opened, Dogfish Head was the smallest brewery, craft or otherwise, in the United States, brewing ten gallons at a time in a system rigged from three kegs and heated by propane burners, three times a day, five days a week. Its first offering was a straight-ahead pale ale using the four ingredients of barley, hops, water, and yeast in those European traditions. Then, during that first year, the brewpub pivoted toward the likes of Chicory Stout, which it debuted as a winter seasonal. It, too, had barley, hops, water, and yeast; it also had Saint-John's-wort, a plant sometimes used to treat depression; organic Mexican coffee; roasted chicory, a plant that can be ground down into a coffee substitute; and licorice root. In other words, it had ingredients that would have been unfamiliarâanathema, reallyâto a Bavarian brewer of the nineteenth or even twentieth century. These ingredients produced a dark, peppery beer with hints, not surprisingly, of roasted coffee and chocolate; it was, as one reviewer put it, perfect “if you only want to have one or two stouts.”

Part of it was boredom with the status quo; part of it the possibility for experimentation; part of it another way to stand out in an increasingly crowded pack whose production was growing by double-digit percentages yearly. Whatever the ultimate reason, Calagione's Chicory Stout was one of the opening salvos in extreme beer and extreme brewing, though neither term would come into vogue for years yet. What characteristics defined extreme beer? Strength: they were typically higher in alcohol per volume than your pales ales, IPAs, and ambers. Richness, too, could be a defining feature; as with

the Chicory Stout, extreme beers tended to be very busy on their back ends, brimming with hitherto unimagined ingredients or with unimagined amounts of those ingredients. Hops would become a favorite tool of extreme brewing, with Dogfish Head pioneering a method for frequently adding hopsâsometimes once a minute for two hoursâto the boiling wort. Finally, because of the first two characteristics, extreme beers were simply exotic to the American palate, even a palate that may now have spent an intimate twenty years with craft beers. They tasted stranger, their packaging even

looked

stranger, than anything out there, the explanations of their origins and the adjectives that might flow from tasting them unlike anything the beer consumer, in the United States or elsewhere, had ever encountered. The definition of extreme beer seemed destined to mimic the popular one for obscenity: people knew it when they saw it.

Boston Beer was perhaps the first brewery in the nation to present extreme beers as exactly that, beginning in the late 1980s with its interpretations of the strong German lager style called bock and then its Utopias line, some bottles of which, it was suggested by Jim Koch, should be aged likeâgasp!âwine. Koch would explain it this way when extreme beer had become a staple of the American craft beer movement: “The world doesn't need one more pale ale or more good porter or hefewiezen. There's enough of that. Craft brewers have to continue to brew unique, distinctive, even surprising beers.”

For the time being, extreme beers did not really have a name or a niche. The vast majority of craft beer produced and consumed in the United States was, as we have seen, on the milder, more traditional side, with Koch's own Boston Lager claiming a sizable share. But Calagione was just twenty-five when his brewpub opened, young enough to have grown up around craft beer's wider availability and after the movement's first shakeout in the 1980s. As a newcomer, he took to the possibilities offered by extreme beer for experimentation and innovation on a scale not seen since the heyday of Belgian beer in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when styles now common worldwide were developed by the isolated equivalents of late-twentieth-century start-ups. Still, for all the enthusiasm engendered by these potential avenues, it remained to be seen whether roasted chicory and Saint-John's-wort in unusual packaging could be a successful financial route; extreme beer might just be a particularly innovative way to go broke. Things were uncertain enough already.

The Dogfish Head brewpub grew in popularity despite its location, its growth powered in no small part by the live music that Calagione booked and the general ambiance of a spot that had embraced “Off-Centered Ales for Off-Centered People” as its slogan. Calagione expanded the brewhouse thirtyfold

to keep up with demand for the beers, consigning the original, ten-gallons-at-a-time system to lore. And then in 1997, a year after the brewpub began bottling that first pale ale, he moved the packaging from the restaurant to a space seven miles away, in Lewes.

Small as it still was, Dogfish Head ran smack into Anheuser-Busch's 100-percent-share-of-mind campaign. At least two distributors told the brewery they did not want to distribute its brands anymore, and when Dogfish Head, now on its way to producing five year-round beers and garnering $1.6 million in annual sales by the decade's end, tried to distribute beyond the Mid-Atlantic, it ran into similar reticence. When a distributor pressured by Anheuser-Busch wouldn't take his brands, Calagione would approach another big distributor in whatever particular market, only to be told he had too many craft brands as it was. In those cases, he would hunt for smaller distributors and count on word of mouth among consumers to stoke demand, as it had done in Rehoboth Beach.

Or he would have some fun with his company's size. Goliath might have the major distributors and the ad men, but David held an increasing fascination with consumers, from Wall Street to Main Street. On the morning of August 24, 1997, a Sunday, Calagione climbed into an eighteen-foot scull he had spent $1,500 making and drifted into the currents of Delaware Bay with a six-pack of his pale ale beside him. He spent about four hours rowing the seventeen nautical miles from Rehoboth Beach to Cape May, New Jersey, to deliver the first Dogfish Head to be distributed outside Delaware. There were only a handful of people to see him disembark, however, and the publicity stunt seemed like a clever flop. Then jeansmaker Levi Strauss learned about the journey and contacted him to appear in an ad campaign photographed by Richard Avedon. The theme? Plucky entrepreneurs.

Petaluma, CA | 1995

T

ony Magee knew that everyone

in craft beer knew the origin of Oktoberfest. The king of Bavaria threw a two-day festival for his newly married son, the crown prince, in October 1810. Ever since, the Germans, and eventually people worldwide, have marked the occasion each year with their own festivals resplendent in copious amounts of beer and German food. Oktoberfest

beers grew from the original festival as well, and Magee's brewery, Lagunitas, was about to debut its own interpretation in October 1995. But first it needed a label, one that would stand out among the other Oktoberfest beers offered by American craft brewers (Jim Koch's Boston Beer had perhaps America's bestselling Oktoberfest interpretation, a lager it introduced in 1989). Magee's backgrounds in music composition and print sales dovetailed nicely as he pored over ideas for what might make a marketplace splash but was also out of the ordinary for a typical Oktoberfest. His was a hoppy amber ale, while most others were lagers on the sweeter side. He wanted a label that stood out both visually and editorially; packaging could be, he realized, as experimental as the stronger beers his brewery was turning out.

It was a realization that other craft brewers, especially the newer ones, were coming to across the country as they eschewed the educational and direct packaging of their pioneer predecessors as much as they eschewed their recipes. The label of a bottle of Anchor Brewing, Sierra Nevada, or Boston Beerâeven the more irreverent Pete's Brewingâmight tell the origins of the beer and the ingredients as well as the pride the brewery took in presenting the product. The accompanying imagery would be equally simple and often the same through a brewery's various styles, little altered except for the ingredients and the packaging's colors, with maybe an addition or omission here and there. These labels were straightforwardâthey had had to be in an era when most consumers would have been unfamiliar with what was staring back at them from the grocery store shelf. Too cute or too arcane and it wouldn't matter how good the beer was inside the brown bottle (which could itself be unfamiliar enough). The imagery on Anchor's label for Liberty Ale, revolutionary for its use of Cascade hops, shared the anchor, barley, hops, and “San Francisco” from the label for the brewery's steam beer (but, unlike the steam beer label, it also had an eagle behind the anchor). It read: