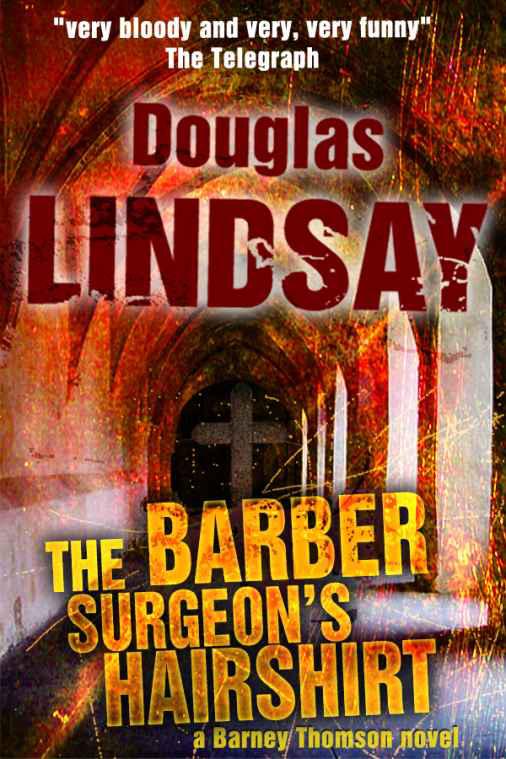

The Barber Surgeon's Hairshirt (Barney Thomson series)

Read The Barber Surgeon's Hairshirt (Barney Thomson series) Online

Authors: Douglas Lindsay

The Barber Surgeon’s Hairshirt

by

Douglas Lindsay

Published by Blasted Heath, 2011

copyright © 2000, 2003, 2011 Douglas Lindsay

A version of this book was published by Piatkus in 2000 and by Long Midnight Publishing in 2003 under the title

The Cutting Edge of Barney Thomson

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission of the author.

Douglas Lindsay has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

All the characters in this book are fictitious and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Cover design by JT Lindroos

Photo by AlicePopkorn2

Visit Douglas Lindsay at:

ISBN (ePub): 978-1-908688-14-9

Version 2-1-3

Novels

Lost in Juarez

Barney Thomson series

The Long Midnight of Barney Thomson

A Prayer for Barney Thomson

The King Was In His Counting House

The Last Fish Supper

The Haunting of Barney Thomson

The Final Cut

Novellas

The End of Days

Dead Money

by Ray Banks

Phase Four

by Gary Carson

The Long Midnight of Barney Thomson

by Douglas Lindsay

The Man in the Seventh Row

by Brian Pendreigh

The Killing of Emma Gross

by Damien Seaman

All The Young Warriors

by Anthony Neil Smith

Keep informed of new releases by signing up to the

Blasted Heath newsletter

. We’ll even send you a free book by way of thanks!

Brother Festus. An honest man. Weird name; honest nevertheless.

They’d called him a variety of things in school. Foetus. Fester. Fetid. Fungus. One Horse, although that’s a completely different story. Neither had he been strong, the schoolboy Festus, and so he’d been teased and bullied, every aspect of his character remorselessly picked apart, exaggerated and turned into an object of ridicule. Hair too long, hair too short; wearing school uniform, not wearing school uniform; gunk in his ears, food in his teeth, gloop in his eyes, Y-fronts too big; no pubes, then later a thick forest of wiry agriculture; voice like a girl, voice like a moron; good at art, bad at tech; chipolata penis, hairy arse, breasts too big, testicles like peas, tongue like a Spam sandwich. Everything.

Somewhere there’s a queue, and it’s populated by comedians just waiting to tell another queue of talk show hosts that their comedy came from being bullied at school. Festus had tried that too, but he

hadn’t

had the jokes, and so there’d been another reason to tease him.

Humour having failed, he’d retreated to that place in the head where everyone goes, but only the sad and solitary remain. And he had never left.

And so, time and bitter experience had brought him to the Holy Order of the Monks of St John, in north-west Sutherland, fifteen years prior to his imminent untimely death. An austere existence to accompany his austere thoughts, for life had taught this man never to attempt to expand his mind. It was a place where no one teased him, and no one cared about the idiosyncrasies which plagued his personality and appearance. He had found his home, a job to suit his underdeveloped intelligence, and people with whom he could associate. Brother Festus was in his element.

He’d arrived in the mid-eighties, and so easily missing the events of Two Tree Hill. He’d heard about them, of course. Low whispers in dark corners, though there was much which was left unsaid. Two Tree Hill; the very name caused Festus’s stomach to churn at the personal memories it induced – the world’s injustice against one man. A man alone, cast from society, as Festus had been himself.

And so, at this time of murder and terror, heartache and horror, the dichotomy of faith against reality, and the continuing serial of corpulent bloodshed, Brother Festus was about to be another victim. Not, however, of the man who wreaked vengeance for the iniquities of Two Tree Hill. Festus was about to fall victim to that other great serial killer – the act of God.

Festus swept the stairs. A small flight leading down into the main part of the abbey church. His brush moved ponderously across cold stone, his eyes never straying from the work he was about. He had to wash them next. Not his usual employment, but the new floor cleaner, Brother Jacob, had vanished. Festus was happy to sweep the floors and the stairs. Happy, in his own way.

The storm raged outside, every crack and joint and bolt and buttress ground its teeth in strained agony. Stained windows stood tight against the wind, inside the church nothing stirred. Not a draught blew, not a mouse roared, not a spider waved a forward leg, not a dog had its day. The strained quiet of the grave, statue and sculpture looking down on the back of Brother Festus as he bent to his work. God’s work.

Sculptures of holy men, whose names had long since been dumped into the damned sepulchre of time; the Virgin Mary, sanguine and resigned to her place in history; a strange, lonely bemused Jesus at the Last Supper, with the disciples nowhere in attendance, while the son of God told his best parables –

There was this bar, right, and in walked a Sadducee, a Pharisee and an Australian

– and no one listened, but for a detached foot, the foot of Judas; the angel Gabriel, a good-looking guy, bearded and sad, eyebrow raised to some melancholy contradiction, a seraph’s question as to the corruption of man and all that lies before him, a sculptor’s vague musing on the limits of consequence; a bitter St Francis, the mad monk, scattering bread, a statement of his sexual desperation, his face lined with pain, his eyes scarred by the decades of frantic do-gooding, defying the black heart which lies within us all; and a substantial gathering of gargoyles, fine figures, their heads no more grotesque than comic caricature, the classic 1400s, pre-Reformation, Gothic Götterdämmerung. One of these, it would be, that would kill poor Brother Festus. By accident, indeed, or perhaps by the hand of God. For God’s hands are, to quote some Italian gangster somewhere,

pretty fucking big, you know what I mean?

Brother Festus moved slowly down onto the floor of the church. Cold stone, under which the bodies of buried Crusaders still lay, their names long since worn from the tombstones of opprobrium, so that most of the brothers were no longer aware of the bare skulls which stared up at them as they walked across the floor.

These were men who had died on the most unholy of Holy Crusades, men for whom the bell had tolled. A dagger in the guts, a scimitar drawn swiftly across the neck, hot oil poured into a tortured open mouth. They all watched Brother Festus, waiting to welcome him to their eternity of tortures.

Festus swept the floors.

What do monks think of when they are about mundane tasks?

God? His existence or otherwise? Deities in general? Some petty infatuation with one of the other monks, or with a long-remembered girl in a photograph which he keeps secreted beneath his mattress? Sport, perhaps, a metaphor for life which once tugged at him, gave him something to live for, so that years later he still recalls the missed birdie opportunity or the dropped catch at silly mid-wicket; the missed smash from the back of the court, the mistimed tackle; the perfect goal unbelievably ruled offside. Or maybe the average monk thinks of nothing as he sweeps the floor. His mind is blank, random visions and thoughts flickering minute distances below the surface, yet never seeing the light.

In that way, Brother Festus was entirely average, his mind an empty desert, thoughts for nothing. And so it was that he did not see the gargoyle, strangely misplaced from its perch upon high, where it had rested for over five hundred years. Resting and waiting; waiting for the opportunity to fall on an unsuspecting monk and to pierce his flesh. A monk like Brother Festus.

Festus swept the floor, mind a long way away. The gargoyle broke away from its base; the stone cracked noiselessly, a precise split. The sort of clean break that you would think only a master craftsman could achieve.

The fall was silent and swift. Five seconds earlier and it would have smashed into the floor in front of Festus; five seconds later and it would have missed him to the rear. But the timing was meticulous and, from on high, from the roof of the church, from the midst of the elaborate super-sculpture, from the gods, it came.

It was an interesting gargoyle, based at the time on a local farmer with a nose like a parsnip. Long, corrugated, and mild to the taste.

The gargoyle spun in free-fall, like a high-diver completing some elaborate octuple somersault, before the fall was sharply arrested as it thumped into Festus and the nose embedded itself into the back of his skull. And stayed there.

Festus collapsed to the floor, the gargoyle impaled upon him by the nose, so that he looked like a man with two heads. The blood seeped out slowly, running down his pallid cheeks and onto the floor; blood from Festus’s head mixing with that from the gargoyle’s bloodied nose.

Festus was dead. The Crusaders lay in wait below, anticipating the arrival of their brother. The abbey church was quiet. Not a mouse roared, not a dog had his day. And somewhere, somewhere, there may have been the sound of the architect of Festus’s timely accident going about his business.

‘What d’you do at the weekend, then?’

‘I can’t believe the lift isn’t working. Twelve sodding floors.’

‘You don’t think the council’s got better things to do with their money than spend it on the bastards who live here? What d’you do at the weekend?’

‘No wonder these places are riddled with low life. They build these sodding great monstrosities bloody miles from the nearest shop or pub. They’ve got nothing.’

‘Don’t give a shit.’

‘Even the sodding lifts don’t work. Imagine you’re some single mum with three weans and ten bags of shopping.’

‘The single mum’s probably about sixteen, and the stupid wee slapper went and shagged some fifth year with a foosty moustache, just so she could get pregnant and get the house. What was she expecting? A bungalow in Bearsden? What d’you do at the weekend?’

‘Nothing, same as every other weekend. You, however, sound like you’ve got something to tell me.’