The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (19 page)

Read The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life Online

Authors: Richard J. Herrnstein,Charles A. Murray

Tags: #History, #Science, #General, #Psychology, #Sociology, #Genetics & Genomics, #Life Sciences, #Social Science, #Educational Psychology, #Intelligence Levels - United States, #Nature and Nurture, #United States, #Education, #Political Science, #Intelligence Levels - Social Aspects - United States, #Intellect, #Intelligence Levels

Finally, McKinley Blackburn and David Neumark have provided

direct evidence in their analysis of white men in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY). Education and intelligence each contributed to a worker’s income, but the smart: men earned most of the extra wage benefit of education during the past decade.

16

The growing economic benefits of either schooling or intelligence are disproportionately embodied in the rising income of educated people with high test scores and in the falling wages earned by less educated people with low scores.

17

This premium for IQ applies even within the high-IQ occupations that we discussed in Chapter 2. In the NLSY, among people holding one of these jobs, the 1989 weekly earnings (expressed in 1990 dollars) of those in the top 10 percent of IQ were $977, compared to $697 for those with IQs below the top 10 percent, for an annual income difference of over $14,000.

18

Even after extracting any effects of their specific occupations (as well as of the differing incomes of men and women), being in the top 10 percent in IQ was still worth over $11,000 in income for those in this collection of prestigious occupations.

This brings us as far as the data on income and intelligence go. Before leaving the topic, we offer several reasons why the wage premium for intelligence might have increased recently and may be expected to continue to increase.

Perhaps most obviously is that technology has increased the economic value of intelligence. As robots replace factory workers, the factory workers’ jobs vanish, but new jobs pop up for people who can design, program, and repair robots. The new jobs are not necessarily going to be filled by the same people, for they require more intelligence than the old ones did. Today’s technological frontier is more complex than yesterday’s. Even in traditional industries like retailing, banking, mining, manufacturing, and farming, management gets ever more complex. The capacity to understand and manipulate complexity, as earlier chapters showed, is approximated by g, or general intelligence. We would have predicted that a market economy, faced with this turn of events, would soon put intelligence on the sales block. It has. Business consultancy is a new profession that is soaking up a growing fraction of the graduates of the elite business schools. The consultants sell mainly their trained intelligence to the businesses paying their huge fees.

A second reason involves the effects of scale, spurred by the growth in the size of corporations and markets since World War II A person who can dream up a sales campaign worth another percentage point or two of market share will be sought after. What “sought after” means in dollars and cents depends on what a point of market share is worth. If it is worth $500,000, the market for his services will produce one range of salaries. If a point of market share is worth $5 million, he is much more valuable. If a point of market share is worth $100 million, he is worth a fortune. Now consider that since just 1960, the average annual sales, per corporation, of America’s five hundred largest industrial corporations has jumped from $1.8 billion to $4.6 billion (both figures in 1990 dollars). The same gigantism has affected the value of everything from the ability to float successful bond offerings to the ability to negotiate the best prices for volume purchases by huge retail chains. The magnitude of the economic consequences of ordinary business transactions has mushroomed, and with it the value of people who can do their work at a marginally higher level of skill. All the evidence we have suggests that such people have, among their other characteristics, high intelligence. There is no reason to think that this process will stop soon.

Then there are the effects of legislation and regulation. Why are certain kinds of lawyers who never see the inside of a courtroom able to command such large fees? In many cases, because a first-rate lawyer can make a difference worth tens of millions of dollars in getting a favorable decision from a government agency or slipping through a tax loophole. Lawyers are not the only beneficiaries. As the rules of the game governing private enterprise become ever more labyrinthine, intelligence grows in value, sometimes in the most surprising places. One of our colleagues is a social psychologist who supplements his university salary by serving as an adviser on jury selection, at a consulting fee of several thousand dollars per day. Based on his track record, his advice raises the probability of a favorable verdict in a liability or patent dispute by about 5 to 10 percent. When a verdict may represent a swing of $100 million, an edge of that size makes him well worth his large fee.

We have not exhausted all the reasons that cognitive ability is becoming more valuable in the labor market, but these will serve to illustrate the theme: The more complex a society becomes, the more valuable are the people who are especially good at dealing with complexity. Barring a change in direction, the future is likely to see the rules

for doing business become yet more complex, to see regulation extend still further, and to raise still higher the stakes for having a high IQ.

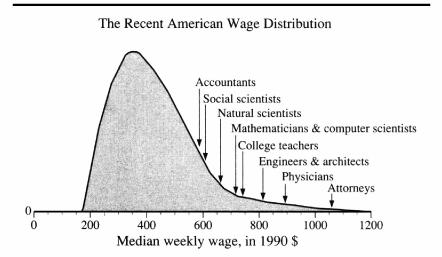

After all that has gone before, it will come as no surprise to find that smart people tend to have high incomes. The advantage enjoyed by those who have high enough IQs to get into the high-IQ occupations is shown in the figure below. All of the high-IQ occupations have median wages well out on the right-hand side of the distribution.

19

Those in the top range of IQ had incomes that were conspicuously above those with lower IQs even within the high-IQ occupations. The overall median family income with a member in one of these occupations and with an IQ in the top 10 percent was $61,100, putting them at the 84th percentile of family incomes for their age group. These fortunate people were newly out of graduate school or law school or medical school, still near the bottom of their earnings trajectory as of their early thirties, whereas a large proportion of those who had gone into blue-collar jobs (disproportionately in the lower IQ deciles) have much less room to advance beyond this age.

20

In other words, the occupational elite is prosperous. Within it, the cognitive elite is more prosperous still.

The high-IQ occupations also are well-paid occupations

Source:

U.S. Department of Labor 1991.

Income as a Family Trait

America has taken great pride in the mobility of generations: enterprising children of poor families are supposed to do better than their parents, and the wastrel children of the rich are supposed to fritter away the family fortune. But in modern America, this mobility has its limits. The experts now believe that the correlation between fathers’ and sons’ income is at least .4 and perhaps closer to .5.

21

Think of it this way: The son of a father whose earnings are in the bottom 5 percent of the distribution has something like one chance in twenty (or less) of rising to the top fifth of the income distribution and almost a fifty-fifty chance of staying in the bottom fifth. He has less than one chance in four of rising above even the median income.

22

Economists search for explanations of this phenomenon in structural features of the economy. We add the element of intellectual stratification. Most people at present are stuck near where their parents were on the income distribution in part because IQ, which has become a major predictor of income, passes on sufficiently from one generation to the next to constrain economic mobility.

The effects of cognitive sorting in education and occupation are reified through geography. People with similar cognitive skills are put together in the workplace and in neighborhoods.

The higher the level of cognitive ability and the greater the degree of homogeneity among people involved in that line of work, the greater is the degree of separation of the cognitive elite from everyone else. First, consider a workplace with a comparatively low level of cognitive homogeneity—an industrial plant. In the physical confines of the plant, all kinds of abilities are being called upon: engineers and machinists,

electricians and pipefitters and sweepers, foremen and shift supervisors, and the workers on the loading dock. The shift supervisors and engineers may have offices that give them some physical separation from the plant floor, but, as manufacturers have come to realize in recent years, they had better not spend all their time in those offices. Efficient and profitable production requires not only that very different tasks be accomplished, using people of every level of cognitive ability, but that they be accomplished cooperatively. If the manufacturing company is prospering, it is likely that a fair amount of daily intermingling of cognitive classes goes on in the plant.

Now we move across the street to the company’s office building. Here the average level of intelligence is higher and the spread is narrower. Only a handful of jobs, such as janitor, can be performed by people with low cognitive ability. A number of jobs can be done by people of average ability—data entry clerks, for example. Some jobs that can be done adequately by people with average cognitive ability turn into virtually a different, and much more important, sort of job if done superbly. The job of secretary is the classic example. The traditional executive secretary, rising through the secretarial ranks until she takes charge of the boss’s office, was once a familiar career path for a really capable, no doubt smart, woman. For still other jobs, cognitive ability is important but less important than other talents—among the sales representatives, for example. And finally there is a layer of jobs among the senior executives and in the R&D department for which cognitive ability is important and where the mean IQ had better be high if the company is to survive and grow in a competitive industry. In the office building, not only cognitive homogeneity has increased; so has physical separation. The executives do not spend much time with the janitors or the data entry clerks. They spend almost all their time interacting with other executives or with technical specialists, which means with people drawn from the upper portion of the ability distribution.

Although corporate offices are more stratified for intelligence than the manufacturing plant, some workplaces are even more stratified. Let’s move across town to a law firm. Once again, the mean IQ rises and the standard deviation narrows. Now there are only a few job categories—for practical purposes, three: secretaries, paralegals or other forms of legal assistants, and the attorneys. The lowest categories, secretarial and paralegal work, require at least average cognitive skills for basic competence, considerably more than that if their jobs are to be done as well

as they could be. The attorneys themselves are likely to be, virtually without exception, at least a standard deviation above the mean, if only because of the selection procedures in the law schools that enabled them to become lawyers in the first place. It remains true that part of the success of the law firm depends on qualities that are only slightly related to cognitive skills—the social skills involved in getting new business, for example. And attorneys in almost any law firm can be found shaking their heads over the highly paid (and smart) partner who is coasting on his subordinates’ talents. But the overall degree of cognitive stratification in a good law firm is extremely high. And note an important distinction: It is not that stratification

within

the law firm is high; rather, the entire workplace represents a stratum highly atypical of cognitive ability in the population at large.

These rarefied environments are becoming more common because the jobs that most demand intelligence are increasing in number and economic importance. These are jobs that may be conducted in cloistered settings in the company of other smart workers. The brightest lawyers and bankers increasingly work away from the courtroom and the bank floor, away from all except the most handpicked of corporate clients. The brightest engineers increasingly work on problems that never require them to visit a construction site or a shop floor. They can query their computers to get the answers they need. The brightest public policy specialists shuttle among think tanks, bureaucracies, and graduate schools of public policy, never having to encounter an angry voter. The brightest youngsters launch their careers in business by getting an M.B.A. from a top business school, thence to climb the corporate ladder without ever having had to sell soap or whatever to the company’s actual customers. In each example, a specialized profession within the profession is developing that looks more and more like academia in the way it recruits, insulates, and isolates members of the cognitive elite.