The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (40 page)

Read The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life Online

Authors: Richard J. Herrnstein,Charles A. Murray

Tags: #History, #Science, #General, #Psychology, #Sociology, #Genetics & Genomics, #Life Sciences, #Social Science, #Educational Psychology, #Intelligence Levels - United States, #Nature and Nurture, #United States, #Education, #Political Science, #Intelligence Levels - Social Aspects - United States, #Intellect, #Intelligence Levels

Most Americans think that crime has gotten far too high. But in the ruminations about how the nation has reached this state and what might be done, too little attention has been given to one of the best-documented relationships in the study of crime: As a group, criminals are below average in intelligence.

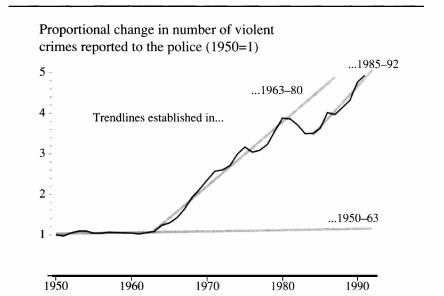

As with so many of the other problems discussed in the previous six chapters, things were not always so bad. Good crime statistics do not go back very far in the United States, but we do not need statistics to remind Americans alive in the 1990s of times when they felt secure walking late at night, alone, even in poor neighborhoods and even in the nation’s largest cities. In the mid-1960s, crime took a conspicuous turn for the worse. The overall picture using the official statistics is shown in the figure below, expressed as multiples of the violent crime rate in 1950.

The figure shows the kind of crime that worries most people most viscerally: violent crime, which consists of robbery, murder, aggravated assault, and rape. From 1950 through 1963, the rate for violent crime was almost flat, followed by an extremely rapid rise from 1964 to 1971, followed by continued increases until the 1980s. The early 1980s saw an interlude in which violent crime decreased noticeably. But the trend-line for 1985-1992 is even steeper than the one for 1963-1980, making it look as if the lull was just that—a brief respite from an increase in violent crime that is now thirty years old.

1

The boom in violent crime after the 1950s

Source: Uniform Crime Reports, annual, Federal Bureau of Investigation.

There is still some argument among the experts about whether the numbers in the graph, drawn from the FBI’s

Uniform Crime Reports,

mean what they seem to mean. But the disagreement has limits. Drawing on sophisticated analyses of these numbers, the consensus conclusions are that victimization studies, based on interviews of crime victims and therefore including crimes not reported to the police, indicate that the increase in the total range of crimes since 1973 has not been as great as the official statistics suggest, but that the increase reflected in the official statistics is also real, capturing changes in crimes that people consider serious enough to warrant reporting to the police.

2

The juvenile delinquents in Leonard Bernstein’s

West Side Story

tell Officer Krupke that they are “depraved on account of we’re deprived,” showing an astute grasp of the poles in criminological theory: the psychological and the sociological.

3

Are criminals psychologically distinct? Or are they ordinary people responding to social and economic circumstances?

Theories of criminal behavior were mostly near the sociological pole from the 1950s through the 1970s. Its leading scholars saw criminals as much like the rest of us, except that society earmarks them for a life of criminality. Some of these scholars went further, seeing criminals as free of personal blame, evening up the score with a society that has victimized them. The most radical theorists from the sociological pole argued that the definition of crime was in itself ideological, creating “criminals” of people who were doing nothing more than behaving in ways that the power structure chose to define as deviant. In their more moderate forms, sociological explanations continue to dominate public discourse. Many people take it for granted, for example, that poverty and unemployment cause crime—classic sociological arguments that are distinguished more by their popularity than by evidence.

4

Theories nearer the psychological pole were more common earlier in the history of criminology and have lately regained acceptance among experts. Here, the emphasis shifts to the characteristics of the offender rather than to his circumstances. The idea is that criminals are distinctive in psychological (perhaps even biological) ways. They are deficient, depending on the particular theory, in conscience or in self-restraint. They lack normal attachment to the mores of their culture, or they are peculiarly indifferent to the feelings or the good opinion of others. They are overendowed with restless energy or with a hunger for adventure or danger. In a term that was in common use throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, chronic offenders may be suffering from “moral insanity.”

5

In other old-fashioned vocabularies, they have been called inhumane, atavistic, demented, monstrous, or bestial—all words that depict certain individuals as something less than human. In their most extreme form, psychological theories say that some people are born criminal, destined by their biological makeup to offend.

We are at neither of these theoretical poles. Like almost all other students of crime, we expect to find explanations from both sociology and psychology. The reason for calling attention to the contrast between the theories is that public discussion has lagged; it remains more nearly stuck at the sociological pole in public discourse than it is among experts. In this chapter, we are interested in the role that cognitive ability plays in creating criminal offenders. This by no means requires us to deny that sociology, economics, and public policy might play an important part in shaping crime rates. On the contrary, we assume that changes in those domains are likely to interact with personal characteristics.

Among the arguments often made against the claim that criminals are psychologically distinctive, two are arguments in principle rather than in fact. We will comment on these two first, because they do not require any extensive review of the factual evidence.

Argument 1 : Crime rates have changed in recent times more than people’s cognitive ability or personalities could have. We must therefore find the reason for the rising crime rates in people’s changing circumstances.

When crime is changing quickly, it seems hard to blame changing personal characteristics rather than changing social conditions. But bear in mind that personal characteristics need not change everywhere in society for crime’s aggregate level in society to change. Consider age, for example, since crime is mainly the business of young people between 15 and 24.

6

When the age distribution of the population shifts toward more people in their peak years for crime, the average level of crime may be expected to rise. Or crime may rise disproportionately if a large bulge in the youthful sector of the population fosters a youth culture that relishes unconventionality over traditional adult values. The exploding crime rate of the 1960s is, for example, partly explained by the baby boomers’ reaching adolescence.

7

Or suppose that a style of child rearing sweeps the country, and it turns out that this style of child rearing leads to less control over the behavior of rebellious adolescents. The change in style of child rearing may predictably be followed, fifteen or so years later, by a change in crime rates. If, in short, circumstances tip toward crime, the change will show up most among those with the strongest tendencies to break laws (or the weakest tendencies to obey them).

8

Understanding those tendencies is the business of theories at the psychological pole.

Argument 2: Behavior is criminal only because society says so. There cannot be psychological tendencies to engage in behavior defined so arbitrarily.

This argument, made frequently during the 1960s and 1970s and always more popular among intellectuals than with the general public, is heard most often opposing any suggestion that criminal behavior has biological roots. How can something so arbitrary, say, as not paying one’s taxes or driving above a 55 mph speed limit be inherited? the critics ask. Behavior regarding taxes and speed limits certainly cannot be coded in our DNA; perhaps even more elemental behaviors such as robbery and murder cannot either.

Our counterargument goes like this: Instead of crime, consider behavior that is less controversial and even more arbitrary, like playing the violin. A violin is a cultural artifact, no less arbitrary than any other man-made object, and so is the musical scale. Yet few people would argue

that the first violinists in the nation’s great orchestras are a random sample of the population. The interests, talents, self-discipline, and dedication that it takes to reach their level of accomplishment have roots in individual psychology—quite possibly even in biology. The variation across people in

any

behavior, however arbitrary, will have such roots. To that we may add that the core crimes represented in the violent crime and property crime indexes—murder, robbery, and assault—are really not so arbitrary, unless the moral codes of human cultures throughout the world may be said to be consistently arbitrary in pretty much the same way throughout recorded human history.

But even if crime is admitted to be a psychological phenomenon, why should intelligence be important? What is the logic that might lead us to expect low intelligence to be more frequently linked with criminal tendencies than high intelligence is?

9

One chain of reasoning starts from the observation that low intelligence often translates into failure and frustration in school and in the job market. If, for example, people of low intelligence have a hard time finding a job, they might have more reason to commit crimes as a way of making a living. If people of low intelligence have a hard time acquiring status through the ordinary ways, crime might seem like a good alternative route. At the least, their failures in school and at work may foster resentment toward society and its laws.

Perhaps the link between crime and low IQ is even more direct. A lack of foresight, which is often associated with low IQ, raises the attractions of the immediate gains from crime and lowers the strength of the deterrents, which come later (if they come at all). To a person of low intelligence, the threats of apprehension and prison may fade to meaninglessness. They are too abstract, too far in the future, too uncertain.

Low IQ may be part of a broader complex of factors. An appetite for danger, a stronger-than-average hunger for the things that you can get only by stealing if you cannot buy them, an antipathy toward conventionality, an insensitivity to pain or to social ostracism, and a host of derangements of various sorts, combined with low IQ, may set the stage for a criminal career.

Finally, there are moral considerations. Perhaps the ethical principles for not committing crimes are less accessible (or less persuasive) to people of low intelligence. They find it harder to understand why robbing someone is wrong, find it harder to appreciate the values of civil

and cooperative social life, and are accordingly less inhibited from acting in ways that are hurtful to other people and to the community at large.

With these preliminaries in mind, let us explore the thesis that, whatever the underlying reasons might be, the people who lapse into criminal behavior are distinguishable from the population at large in their distribution of intelligence.

The statistical association between crime and cognitive ability has been known since intelligence testing began in earnest. The British physician Charles Goring mentioned a lack of intelligence as one of the distinguishing traits of the prison population that he described in a landmark contribution to modern criminology early in the century.

10

In 1914, H. H. Goddard, an early leader in both modern criminology and the use of intelligence tests, concluded that a large fraction of convicts were intellectually subnormal.

11

The subsequent history of the study of the link between IQ and crime replays the larger story of intelligence testing, with the main difference being that the attack on the IQ/crime link began earlier than the broader attempt to discredit IQ tests. Even in the 1920s, the link was called into question, for example, by psychologist Carl Murchison, who produced data showing that the prisoners of Leavenworth had a higher mean IQ than that of enlisted men in World War I.

12

Then in 1931, Edwin Sutherland, America’s most prominent criminologist, wrote “Mental Deficiency and Crime,” an article that effectively put an end to the study of IQ and crime for half a century.

13

Observing (accurately) that the ostensible IQ differences between criminals and the general population were diminishing as testing procedures improved, Sutherland leaped to the conclusion that the remaining differences would disappear altogether as the state of the art improved.

The difference, in fact, did not disappear, but that did not stop criminology from denying the importance of IQ as a predictor of criminal behavior. For decades, criminologists who followed Sutherland argued that the IQ numbers said nothing about a real difference in intelligence between offenders and nonoffenders. They were skeptical about whether the convicts in prisons were truly representative of offenders

in general, and they disparaged the tests’ validity. Weren’t tests just measuring socioeconomic status by other means, and weren’t they biased against the people from the lower socioeconomic classes or the minority groups who were most likely to break the law for other reasons? they asked. By the 1960s, the association between intelligence and crime was altogether dismissed in criminology textbooks, and so it remained until recently. By the end of the 1970s, students taking introductory courses in criminology could read in one widely used textbook that the belief in a correlation between low intelligence and crime “has almost disappeared in recent years as a consequence of more cogent research findings,”

14

or learn from another standard textbook of “the practical abandonment of feeblemindedness as a cause of crime.”

15