The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (57 page)

Read The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life Online

Authors: Richard J. Herrnstein,Charles A. Murray

Tags: #History, #Science, #General, #Psychology, #Sociology, #Genetics & Genomics, #Life Sciences, #Social Science, #Educational Psychology, #Intelligence Levels - United States, #Nature and Nurture, #United States, #Education, #Political Science, #Intelligence Levels - Social Aspects - United States, #Intellect, #Intelligence Levels

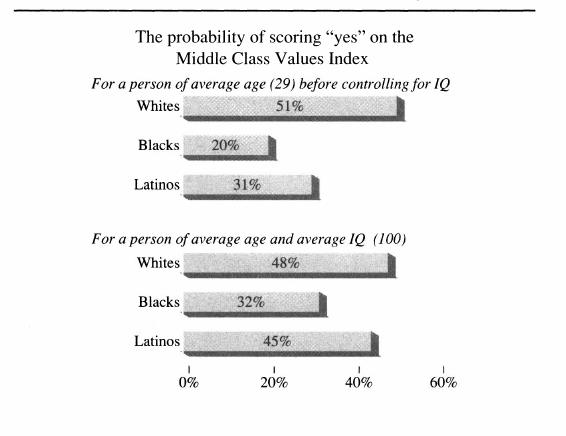

We concluded Part II with the Middle Class Values (MCV) Index, which scores a “yes” for those young adults in the NLSY who were still married to their first spouse, in the labor force if they were men, bearing their children within marriage if they were women, and staying out of jail, and scores a “no” for those who failed any of those criteria. Never-married people who met all the other criteria were excluded. The MCV Index, as unsophisticated as it is, has a serious purpose: It captures a set of behaviors that together typify (though obviously do not define) “solid citizens.” Having many such citizens is important for the creation of peaceful and prosperous communities. The figure below shows what happens when the MCV Index is applied to different ethnic groups, first adjusting only for age and then controlling for IQ as well. (In interpreting these data, bear in mind that large numbers of people of all ethnicities who did not score “yes” are leading virtuous and productive lives.) The ethnic disparities remain instructive. Before controlling for IQ, large disparities separate both Latinos and blacks from whites. But given average IQ, the Latino-white difference shrank to three percentage points. The difference between blacks and whites and Latinos remains substantial, though only about half as large as it was before controlling for IQ. This outcome is not surprising, given what we have already shown about ethnic differences on the indicators that go into the MCV Index, but it nonetheless points in a summary fashion to a continuing divergence between blacks and the rest of the American population in some basic social and economic behaviors.

The MCV Index, before and after controlling for IQ

If one of America’s goals is to rid itself of racism and institutional discrimination, then we should welcome the finding that a Latino and white of similar cognitive ability have the same chances of getting a bachelor’s degree and working in a white-collar job. A black with the same cognitive ability has an even higher chance than either the Latino or white of having those good things happen. A Latino, black, and white of similar cognitive ability earn annual wages within a few hundred dollars of one another.

Some ethnic differences are not washed away by controlling either for intelligence or for any other variables that we examined. We leave those remaining differences unexplained and look forward to learning from our colleagues where the explanations lie. We urge only that they explore those explanations after they have extracted the role—often the large role—that cognitive ability plays.

Similarly, the evidence presented here should give everyone who writes and talks about ethnic inequalities reason to avoid flamboyant rhetoric about ethnic oppression. Racial and ethnic differences in this country are seen in a new light when cognitive ability is added to the picture. Awareness of these relationships is an essential first step in trying to construct an equitable America.

The Demography of Intelligence

When people die, they are not replaced one for one by babies who will develop identical IQs. If the new babies grow up to have systematically higher or lower IQs than the people who die, the national distribution of intelligence changes. Mounting evidence indicates that demographic trends are exerting downward pressure on the distribution of cognitive ability in the United States and that the pressures are strong enough to have social consequences.

Throughout the West, modernization has brought falling birth rates. The rates fall faster for educated women than the uneducated. Because education is so closely linked with cognitive ability, this tends to produce a dysgenic effect, or a downward shift in the ability distribution. Furthermore, education leads women to have their babies later—which alone also produces additional dysgenic pressures.

The professional consensus is that the United States has experienced dysgenic pressures throughout either most of the century (the optimists) or all of the century (the pessimists). Women of all races and ethnic groups follow this pattern in similar fashion. There is some evidence that blacks and Latinos are experiencing even more severe dysgenic pressures than whites, which could lead to further divergence between whites and other groups in future generations.

The rules that currently govern immigration provide the other major source of dysgenic pressure. It appears that the mean IQ of immigrants in the 1980s works out to about 95. The low IQ may not be a problem; in the past, immigrants have sometimes shown large increases on such measures. But other evidence indicates that the self-selection process that used to attract the classic American immigrant—brave, hard working, imaginative, self-starting, and often of high IQ—has been changing, and with it the nature of some of the immigrant population.

Putting the pieces together, something worth worrying about is happening to the cognitive capital of the country. Improved health, education, and childhood interventions may hide the demographic effects, but that does not reduce

their importance. Whatever good things we can accomplish with changes in the environment would be that much more effective if they did not have to fight a demographic head wind.

S

o far, we have been treating the distribution of intelligence as a fixed entity. But as the population replenishes itself from generation to generation by birth and immigration, the people who pass from the scene are not going to be replaced, one for one, by other people with the same IQ scores. This is what we mean by the demography of intelligence. The question is not whether demographic processes in and of themselves can have an impact on the distribution of scores—that much is certain—but what and how big the impact is, compared to all the other forces pushing the distribution around. Mounting evidence indicates that demographic trends are exerting downward pressures on the distribution of cognitive ability in the United States and that the pressures are strong enough to have social consequences.

We will refer to this downward pressure as

dysgenesis,

borrowing a term from population biology. However, it is important once again not to be sidetracked by the role of genes versus the role of environment. Children resemble their parents in IQ, for whatever reason, and immigrants and their descendants may not duplicate the distribution of America’s resident cognitive ability distribution. If women with low scores are reproducing more rapidly than women with high scores, the distribution of scores will, other things equal, decline, no matter whether the women with the low scores came by them through nature or nurture.

1

More generally, if population growth varies across the range of IQ scores, the next generation will have a different distribution of scores.

2

In trying to foresee changes in American life, what matters is

how

the distribution of intelligence is changing, more than

why.

Our exploration of this issue will proceed in three stages. First, we will describe the state of knowledge about when and why dysgenesis occurs. Next, we will look at the present state of affairs regarding differential birth rates, differential age of childbearing, and immigration. Finally, we will summarize the shape of the future as best we can discern it and describe the magnitude of the stakes involved.

The understanding of dysgenesis has been a contest between pessimists and optimists. For many decades when people first began to think systematically about intelligence and reproduction in the late nineteenth century, all was pessimism. The fertility rate in England began to fall in the 1870s, and it did not take long for early students of demography to notice that fertility was declining most markedly at the upper levels of social status, where the people were presumed to be smarter.

3

The larger families were turning up disproportionately in the lower classes. Darwin himself had noted that even within the lower classes, the smaller families had the brighter, the more “prudent,” people in them.

All that was needed to conclude that this pattern of reproduction was bad news for the genetic legacy was arithmetic, argued the British scholars around the turn of the twentieth century who wanted to raise the intelligence of the population through a new science that they called eugenics.

4

Their influence crossed the ocean to the United States, where the flood of immigrants from Russia, eastern Europe, and the Mediterranean raised a similar concern. Were those huddled masses bringing to our shores a biological inheritance inconsistent with the American way of life? Some American eugenicists thought so, and they said as much to the Congress when it enacted the Immigration Act of 1924, as we described in the Introduction.

5

Then came scientific enlightenment—the immigrants did not seem to be harming America’s genetic legacy a bit—followed by the terrors of nazism and its perversion of eugenics that effectively wiped the idea from public discourse in the West. But at bottom, the Victorian eugenicists and their successors had detected a demographic pattern that seems to arise with great (though not universal) consistency around the world.

For this story, let us turn first to a phenomenon about which there is no serious controversy, the

demographic transition.

Throughout the world, the premodern period is characterized by a balance between high death rates and high birth rates in which the population remains more or less constant. Then modernization brings better hygiene, nutrition, and medicine, and death rates begin to fall. In the early phases of modernization, birth rates remain at their traditional levels, sustained by deeply embedded cultural and social traditions that encourage big families,

and population grows swiftly. But culture and tradition eventually give way to the attractions of smaller families and the practical fact that when fewer children die, fewer children need to be born to achieve the same eventual state of affairs. Intrinsic birth rates begin to decline, and eventually the population reaches a slow-or no-growth state.

6

The falling birth rate is a well known and widely studied feature of the demographic transition. What is less well known, but seems to be true among Western cultures that have passed through the demographic transition, is that declines in lifetime fertility occur disproportionately among educated women and women of higher social status (we will refer to such women as “privileged”), just as the Victorians thought.

7

Why? One reason is that privileged women lose their reproductive advantage. In premodern times, privileged young women were better nourished, better rested, and had better medical care than the unprivileged. They married earlier and suffered fewer marital disruptions.

8

The net result was that, on average, they ended up with more surviving children than did unprivileged women. As modernization proceeds, these advantages narrow. Another reason is that modern societies provide greater opportunities for privileged women to be something other than full-time mothers. Marriage and reproduction are often deferred for education, for those women who have access to it. On the average, they spend more of their reproductive years in school because they do well in school, because their families support their schooling, or both. Negative correlations between fertility and educational status are likely to be the result.

Even after the school years, motherhood imposes greater cost in lost opportunities on a privileged woman than on an unprivileged one in the contemporary West.

9

A child complicates having a career, and may make a career impossible. Ironically, even monetary costs work against motherhood among privileged women. By our definition, privileged women have more money than deprived women, but for the privileged woman, a child entails expenses that can strain even a high income—from child care for the infant to the cost of moving to an expensive suburb that has a good school system when the child gets older. In planning for a baby—and privileged women tend to plan their babies carefully—such costs are not considered optional but what

must

be spent to raise a child properly. The cost of children is one more reason that privileged women bear few children and postpone the ones they do bear.

10

Meanwhile, children are likely to impose few opportunity costs on a

very poor woman; a “career” is not usually seen as a realistic option. Children continue to have the same attractions that have always led young women to find motherhood intrinsically rewarding. And for women near the poverty line in most countries in the contemporary West, a baby is either free or even profitable, depending on the specific terms of the welfare system in her country.