The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (101 page)

Read The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Tags: #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Social History, #21st Century, #Crime, #Anthropology, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Criminology

Today homosexuality has been legalized in almost 120 countries, though laws against it remain on the books of another 80, mostly in Africa, the Caribbean, Oceania, and the Islamic world.

229

Worse, homosexuality is punishable by death in Mauritania, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Yemen, parts of Nigeria, parts of Somalia, and all of Iran (despite, according to Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, not existing in that country). But the pressure is on. Every human rights organization considers the criminalization of homosexuality to be a human rights violation, and in 2008 in the UN General Assembly, 66 countries endorsed a declaration urging that all such laws be repealed. In a statement endorsing the declaration, Navanethem Pillay, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, wrote, “The principle of universality admits no exception. Human rights truly are the birthright of all human beings.”

230

229

Worse, homosexuality is punishable by death in Mauritania, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Yemen, parts of Nigeria, parts of Somalia, and all of Iran (despite, according to Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, not existing in that country). But the pressure is on. Every human rights organization considers the criminalization of homosexuality to be a human rights violation, and in 2008 in the UN General Assembly, 66 countries endorsed a declaration urging that all such laws be repealed. In a statement endorsing the declaration, Navanethem Pillay, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, wrote, “The principle of universality admits no exception. Human rights truly are the birthright of all human beings.”

230

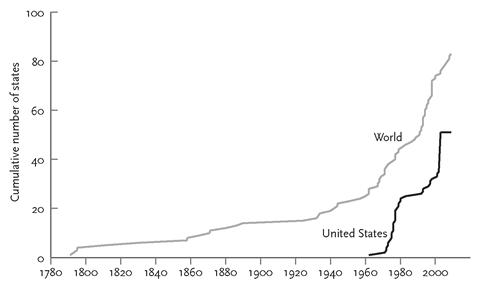

FIGURE 7–23.

Time line for the decriminalization of homosexuality, United States and world

Time line for the decriminalization of homosexuality, United States and world

Sources:

Ottosson, 2006, 2009. Dates for an additional seven countries (Timor-Leste, Surinam, Chad, Belarus, Fiji, Nepal, and Nicaragua) were obtained from “LBGT Rights by Country or Territory,”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LGBT_rights

. Dates for an additional thirty-six countries that currently allow homosexuality are not listed in either source.

Ottosson, 2006, 2009. Dates for an additional seven countries (Timor-Leste, Surinam, Chad, Belarus, Fiji, Nepal, and Nicaragua) were obtained from “LBGT Rights by Country or Territory,”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LGBT_rights

. Dates for an additional thirty-six countries that currently allow homosexuality are not listed in either source.

The same graph shows that the decriminalization of homosexuality began later in the United States. As late as 1969, homosexuality was illegal in every state but Illinois, and municipal police would often relieve their boredom on a slow night by raiding a gay hangout and dispersing or arresting the patrons, sometimes with the help of billy clubs. But in 1969 a raid of the Stonewall Inn, a gay dance club in Greenwich Village, set off three days of rioting in protest and galvanized gay communities throughout the country to work to repeal laws that criminalized homosexuality or discriminated against homosexuals. Within a dozen years almost half of American states had decriminalized homosexuality. In 2003, following another burst of decriminalizations, the Supreme Court overturned an antisodomy statute in Texas and ruled that all such laws were unconstitutional. In the majority opinion, Justice Anthony Kennedy invoked the principle of personal autonomy and the indefensibility of using government power to enforce religious belief and traditional customs:

Liberty presumes an autonomy of self that includes freedom of thought, belief, expression, and certain intimate conduct.... It must be acknowledged, of course, that for centuries there have been powerful voices to condemn homosexual conduct as immoral. The condemnation has been shaped by religious beliefs, conceptions of right and acceptable behavior, and respect for the traditional family.... These considerations do not answer the question before us, however. The issue is whether the majority may use the power of the State to enforce these views on the whole society through operation of the criminal law.

231

Between the first burst of legalization in the 1970s and the collapse of the remaining laws a decade and a half later, Americans’ attitudes toward homosexuality underwent a sea change. The rise of AIDS in the 1980s mobilized gay activist groups and led many celebrities to come out of the closet, while others were outed posthumously. They included the actors John Gielgud and Rock Hudson, the singers Elton John and George Michael, the fashion designers Perry Ellis, Roy Halston, and Yves Saint Laurent, the athletes Billie Jean King and Greg Louganis, and the comedians Ellen DeGeneres and Rosie O’Donnell. Popular entertainers such as k.d. lang, Freddie Mercury, and Boy George flaunted gay personas, and playwrights such as Harvey Fierstein and Tony Kushner wrote about AIDS and other gay themes in popular plays and movies. Lovable gay characters began to appear in romantic comedies and in sitcoms such as

Will and Grace

and

Ellen

, and an acceptance of homosexuality among heterosexuals was increasingly depicted as the norm. As Jerry Seinfeld and George Costanza insisted, “

We’re not gay!

. . . Not that there’s anything wrong with that.” As homosexuality was becoming destigmatized, domesticated, and even ennobled, fewer gay people felt the need to keep their sexual orientation hidden. In 1990 my graduate advisor, an eminent psycholinguist and social psychologist who was born in 1925, published an autobiographical essay that began, “When Roger Brown comes out of the closet, the time for courage is past.”

232

Will and Grace

and

Ellen

, and an acceptance of homosexuality among heterosexuals was increasingly depicted as the norm. As Jerry Seinfeld and George Costanza insisted, “

We’re not gay!

. . . Not that there’s anything wrong with that.” As homosexuality was becoming destigmatized, domesticated, and even ennobled, fewer gay people felt the need to keep their sexual orientation hidden. In 1990 my graduate advisor, an eminent psycholinguist and social psychologist who was born in 1925, published an autobiographical essay that began, “When Roger Brown comes out of the closet, the time for courage is past.”

232

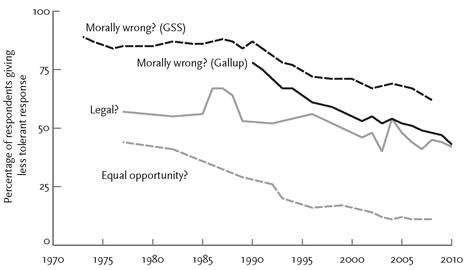

Americans increasingly felt that gay people were a part of their real and virtual communities, and that made it harder to keep them outside their circle of sympathy. The changes can be seen in the attitudes they revealed to pollsters. Figure 7–24 shows Americans’ opinions on whether homosexuality is morally wrong (from two polling organizations), whether it should be legal, and whether gay people should have equal job opportunities. I’ve plotted the “yeses” for the last two questions upside down, so that low values for all four questions represent the more tolerant response.

The most gay-friendly opinion, and the first to show a decline, was on equal opportunity. After the civil rights movement, a commitment to fairness had become common decency, and Americans were unwilling to accept discrimination against gay people even if they didn’t approve of their lifestyle. By the new millennium resistance to equal opportunity had fallen into the zone of crank opinion. Beginning in the late 1980s, the moral judgments began to catch up with the sense of fairness, and more and more Americans were willing to say, “Not that there’s anything wrong with that.” The headline of a 2008 press release from the Gallup Organization sums up the current national mood: “Americans Evenly Divided on Morality of Homosexuality: However, majority supports legality and acceptance of gay relations.”

233

233

FIGURE 7–24.

Intolerance of homosexuality in the United States, 1973–2010

Intolerance of homosexuality in the United States, 1973–2010

Sources:

Morally wrong (GSS): General Social Survey,

http://www.norc.org/GSS+Website

. All other questions: Gallup, 2001, 2008, 2010. All data represent “yes” responses; data for the “Equal opportunity” and “Legal” questions are subtracted from 100.

Morally wrong (GSS): General Social Survey,

http://www.norc.org/GSS+Website

. All other questions: Gallup, 2001, 2008, 2010. All data represent “yes” responses; data for the “Equal opportunity” and “Legal” questions are subtracted from 100.

Liberals are more accepting of homosexuality than conservatives, whites more accepting than blacks, and the secular more tolerant than the religious. But in every sector the trend over time is toward tolerance. Personal familiarity matters: a 2009 Gallup poll showed that the six in ten Americans who have an openly gay friend, relative, or co-worker are more favorable to legalized homosexual relations and to gay marriage than the four in ten who don’t. But tolerance is now widespread: even among Americans who have never known a gay person, 62 percent say they would feel comfortable around one.

234

234

And in the most significant sector of all, the change has been dramatic. Many people have informed me that younger Americans have become homophobic, based on the observation that they use “That’s so gay!” as a putdown. But the numbers say otherwise: the younger the respondents, the more accepting they are of homosexuality.

235

Their acceptance, moreover, is morally deeper. Older tolerant respondents have increasingly come down on the “nature” side of the debate on the causes of homosexuality, and naturists are more tolerant than nurturists because they feel that a person cannot be condemned for a trait he never chose. But teens and twenty-somethings are more sympathetic to the nurture explanation

and

they are more tolerant of homosexuality. The combination suggests that they just find nothing wrong with homosexuality in the first place, so whether gay people can “help it” is beside the point. The attitude is: “Gay? Whatever, dude.” Young people, of course, tend to be more liberal than their elders, and it’s possible that as they creep up the demographic totem pole they will lose their acceptance of homosexuality. But I doubt it. The acceptance strikes me as a true generational difference, one that this cohort will take with them as they become geriatric. If so, the country will only get increasingly tolerant as their homophobic elders die off.

235

Their acceptance, moreover, is morally deeper. Older tolerant respondents have increasingly come down on the “nature” side of the debate on the causes of homosexuality, and naturists are more tolerant than nurturists because they feel that a person cannot be condemned for a trait he never chose. But teens and twenty-somethings are more sympathetic to the nurture explanation

and

they are more tolerant of homosexuality. The combination suggests that they just find nothing wrong with homosexuality in the first place, so whether gay people can “help it” is beside the point. The attitude is: “Gay? Whatever, dude.” Young people, of course, tend to be more liberal than their elders, and it’s possible that as they creep up the demographic totem pole they will lose their acceptance of homosexuality. But I doubt it. The acceptance strikes me as a true generational difference, one that this cohort will take with them as they become geriatric. If so, the country will only get increasingly tolerant as their homophobic elders die off.

A populace that accepts homosexuality is likely not just to disempower the police and courts from using force against gay people but to empower them to prevent other citizens from using it. A majority of American states, and more than twenty countries, have hate-crime laws that increase the punishment for violence motivated by a person’s sexual orientation, race, religion, or gender. Since the 1990s the federal government has been joining them. The most recent escalation came from the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr., Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2009, named after a gay student in Wyoming who in 1998 was beaten, tortured, and tied to a fence overnight to die. (The law’s other namesake was the African American man who was murdered that year by being dragged behind a truck.)

So tolerance of homosexuality has gone up, and tolerance of antigay violence has gone down. But have the new attitudes and laws caused a downturn in homophobic violence? The mere fact that gay people have become so much more visible, at least in urban, coastal, and university communities, suggests they feel less menaced by an implicit threat of violence. But it’s not easy to show that rates of actual violence have changed. Statistics are available only for the years since 1996, when the FBI started to publish data on hate crimes broken down by the motive, the victim, and the nature of the crime.

236

Even these numbers are iffy, because they depend on the willingness of the victims to report a crime and on the local police to categorize it as a hate crime and report it to the FBI.

237

That isn’t as much of a problem with homicides, but unfortunately for social scientists (and fortunately for humanity) not that many people are killed because they are gay. Since 1996 the FBI has recorded fewer than 3 antigay homicides a year from among the 17,000 or so that are committed for every other reason. And as best as we can tell, other antigay hate crimes are uncommon as well. In 2008 the chance that a person would be a victim of aggravated assault because of sexual orientation was 3 per 100,000 gay people, whereas the chance that he would be a victim because he was a human being was more than a hundred times higher.

238

236

Even these numbers are iffy, because they depend on the willingness of the victims to report a crime and on the local police to categorize it as a hate crime and report it to the FBI.

237

That isn’t as much of a problem with homicides, but unfortunately for social scientists (and fortunately for humanity) not that many people are killed because they are gay. Since 1996 the FBI has recorded fewer than 3 antigay homicides a year from among the 17,000 or so that are committed for every other reason. And as best as we can tell, other antigay hate crimes are uncommon as well. In 2008 the chance that a person would be a victim of aggravated assault because of sexual orientation was 3 per 100,000 gay people, whereas the chance that he would be a victim because he was a human being was more than a hundred times higher.

238

We don’t know whether these odds have gotten smaller over time. Since 1996 there has been no significant change in the incidence of three of the four major kinds of hate crimes against gay people: aggravated assault, simple assault, or homicide (though the homicides are so rare that trends would be meaningless anyway).

239

In figure 7–25 I’ve plotted the incidence of the remaining category, which

has

declined, namely intimidation (in which a person is made to feel in danger for his or her personal safety), together with the rate ofof aggravated assault for comparison.

239

In figure 7–25 I’ve plotted the incidence of the remaining category, which

has

declined, namely intimidation (in which a person is made to feel in danger for his or her personal safety), together with the rate ofof aggravated assault for comparison.

Other books

El rapto de la Bella Durmiente by Anne Rice

Rollover by James Raven

You Again by Carolyn Scott

Rumors of Salvation (System States Rebellion Book 3) by Dietmar Wehr

The Best Bad Luck I Ever Had by Kristin Levine

A Torment of Savages (The Reanimation Files Book 4) by A. J. Locke

Wild legacy by Conn, Phoebe, Copyright Paperback Collection (Library of Congress) DLC

Deceived - Part 3 Chloe's Revenge by Carter, Eve

Dark Places by Gillian Flynn