The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History (39 page)

Read The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History Online

Authors: Daniel Diehl

Chinese garrotte.

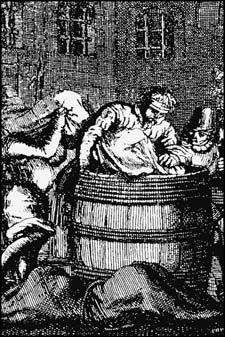

Partial drowning.

WOODEN HORSE

This torture, predominantly employed by the Spanish Inquisition, could be used alone or as a part of the

Tormento de Toca

, described under the section ‘Torture by Water’. The ‘wooden horse’ in question was a shallow box, much like a trough, large enough for a man to lie down in, that was either fitted with legs or placed on a table. At the point inside the trough where a victim’s waist would be, an iron bar extended from one side to the other. When a man was placed in the trough this bar would rest in the small of the back, preventing him from lying flat on the bottom of the box. Once in position, the victim was securely bound with small ropes threaded through holes in the bottom of the box. Ropes were usually placed around his arms, thighs and shins and then pulled so tight – sometimes with the help of cranks – that they would cut through the flesh and cut nearly to the bone. At this point, if the torture master chose to administer even further agony, any one of several forms of water torture, described elsewhere in this section, was begun.

TORTURE BY PUBLIC DISPLAY, SHAME AND HUMILIATION

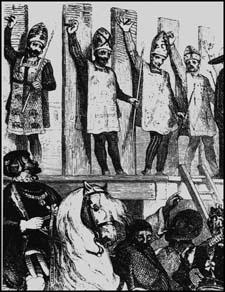

AUTO-DE-FE

Used as an adjunct to the Spanish Inquisition’s memorably cruel punishments of torture and burning at the stake, the

auto-de-fe

(literally ‘act of faith’ in Spanish) was a public ceremony where both the condemned and those who had repented their ‘heresies’ were forced to parade through the streets of town in vast processions while displaying physical signs of their particular transgressions. Some wore signs around their neck with their crime written for all to read while others, who had recanted and were to be spared the burning post, wore inverted flames sewn to the back of their gowns. Those who were to be burnt wore upright flames. When the parade reached the appointed place, the entire assembly took part in a religious service before the condemned were handed over to secular authorities to be run through a nearly instantaneous justice mill before being tied to a burning post and set on fire.

Auto-de-fe.

BRANKS – MASKS OF SHAME OR INFAMY

(See also Scold’s Bridle.) These devices (which are closely related to the scold’s bridle described below in this section) existed in a wide variety of fantastical and sometimes downright artistic styles from about 1500 to 1800. They were used to punish those who, by their words, had transgressed against the prevailing conventions. In the course of four centuries, countless women decried as ‘scolds’ and ‘shrews’ because domestic slavery and incessant pregnancy reduced them to neurasthenia and frenzy were thus humiliated and tortured; political power thus held up to public ridicule the petty disobedient and the nonconformists; ecclesiastical power thus punished a long list of lesser infractions. The overwhelming majority of victims were always women, and the operative principle was

mulier taceat in ecclesia

, ‘Let the woman be silent in church’ – ‘church’ here meaning the ruling ecclesiastical and secular hierarchies, both constitutionally gynaecophobic. The sense was thus: ‘Let the woman be silent in the presence of the male’. The victims, locked into the masks and staked out in the town square, were also treated roughly by the crowd. Painful beatings, besmearing with faeces and urine, and serious, sometimes fatal wounding (especially in the breasts, anus and vagina) was their lot.

Brank.

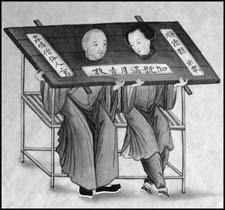

Chinese double cangue.

CANGUE

This Chinese device, alternately known as the

fcan hao, tcha

and

ea

, was a massive wooden collar worn by those condemned to display their crime in public for a prescribed period of time. The donut-like

cangue

was made in two sections, held together by a hinge, which could be opened up to allow the victim to place their head into a hole in the centre. The collar was then closed and locked into place. The

cangue

made it impossible for the wearer to lie down or, in the most extreme and unusual instances of size, even to walk or stand up without risking breaking his neck. Not to mention the complete impossibility of reaching one’s own mouth to eat or drink, thereby having to rely on the charitable compassion of others.

Chucking stool.

CHUCKING STOOL

Devised some time prior to the Norman Conquest of 1066 (when it was known by its Latin name

cathedra stercoris

), this uniquely English form of humiliation was reserved for women who simply could not, or would not, learn how to control their sharp tongues. In the words of the day, it was: ‘a seat of infamy where strumpets and scolds, with bared feet and head, are condemned to abide the jibes of those who pass by’. The chucking stool itself was no more than a wooden arm-chair mounted on two poles, much like an open sedan chair of the eighteenth century. A hole was cut in the bottom of the chair and the victim’s skirts were hoisted up, leaving her exposed rump visible for all to see while she was paraded through the streets of town.

Chucking stool.

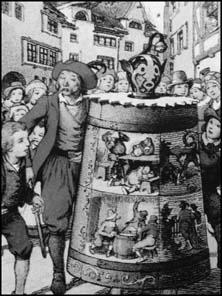

DRUNKARD’S CLOAK

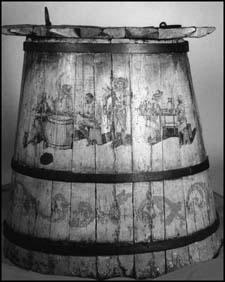

Devised by King James I of England (and quite possibly having been brought into use while James was still reigning in Scotland as James VI) the drunkard’s cloak (occasionally referred to as the ‘barrel pillory’) was a perfect example of letting the punishment fit the crime. Nothing more than a large beer keg with the bottom knocked out and a hole cut into the top large enough for a man’s head to fit through, those convicted of habitual public inebriation were forced to wear the ‘cloak’ whenever they went out in public for a specified period of time. Sometimes additional holes were cut into the sides so the victim could use their hands to help support the barrel’s weight. To prevent the victim from simply stepping out of the thing a locking collar of wood or metal was placed around their neck. While this may seem laughable, anyone who has ever tried to lift a full-sized, 36-gallon wooden cask knows how heavy they are. The drunkard’s cloak was not only a horribly chaffing thing, but its weight could easily tear the muscles connecting the neck to the shoulders. There are records of the cloak remaining in use as late as 1690 when Samuel Pepys, then Secretary of the Royal Navy, mentioned it in his diaries.

Drunkard’s cloak.