The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History (42 page)

Read The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History Online

Authors: Daniel Diehl

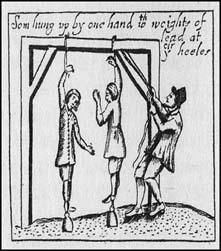

Gibbet

GIBBET

The gibbet was a cage made of iron straps, invented in the sixteenth century and intended for the display of corpses after the victim had been hanged, thus providing a long-term warning to other would-be miscreants. When no proper gibbet was available, the corpse might be wrapped in chains and hung from any convenient tree. Naturally, at some point, an inventively cruel person – quite possibly Henry VIII – wondered what would happen if a condemned man were simply locked in a gibbet and left to twist in the wind until he died of exposure or starvation. Living or dead, victims of the gibbet became so numerous that they littered Europe’s landscape like signposts, often being used as directional guideposts for travellers: ‘Over the stone bridge, past the gibbet and on into the village’. For those unfortunate enough to be gibbeted alive there were occasional grotesque embellishments such as that recorded by an English traveller visiting Germany in the early 1600s: ‘Near Lindau I did see a malefactor hanging in iron chains in the gallows with a massive dog hanging on each side by the heels, as being nearly starved, they might eat the flesh of the malefactor before he himself died of famine …’ To add variety to what could easily have become stale sport, some criminals were placed in gibbets, or wrapped in chains, and suspended over the shoreline at low tide. As the tide came in they would be engulfed by the sea.

Suspension.

Gibbet.

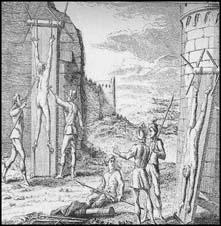

HANGING

Hanging is not technically a torture but a method of execution. However, until the mid-nineteenth-century invention of the ‘drop method’ – wherein a trap door in the floor of the gallows is sprung open, allowing the victim to fall approximately 6ft, breaking their neck – hanging was anything but the relatively swift death we often assume it to be. Those condemned to be hanged simply had a noose slipped over their head and were then hauled into the air and left to kick and dangle until they choked to death. Depending upon the weight and physical condition of the victim this could take anywhere from five to twenty minutes. In many instances, friends of the condemned helped things along by grabbing on to the victim’s legs and pulling downward as hard as they could. History’s most notorious place of hanging is undoubtedly London’s Tyburn (located where Marble Arch now stands and commemorated with a bronze plaque set in the pavement). Having been used as a place of punishment and execution since 1196, throughout the Middle Ages and well into the eighteenth century Tyburn rivalled, and later overcame, Smithfield Horse Market as the place where the greatest number of English executions took place. In 1571, a permanent gallows, popularly known as the Tyburn Tree, was erected at a crossroads in the village of Tyburn. The ‘tree’ in question consisted of three stout posts, set into the ground in a triangular pattern, and rising nearly 20ft into the air. The top of these posts were then connected by three cross braces, which formed a large triangle. Over the next 212 years uncounted thousands of convicts would meet their end amid the jeers, cheers and cat-calls of heaving crowds of onlookers. Because of the triangular structure of the gallows, numerous victims could be accommodated at one time. The greatest number of simultaneous executions took place on 23 June 1649 when twenty-three men and one woman did what was popularly known as ‘dance the Tyburn jig’. Tyburn Tree was demolished in 1783 but hanging remained universally popular well into the twentieth century.

Racking and rending.

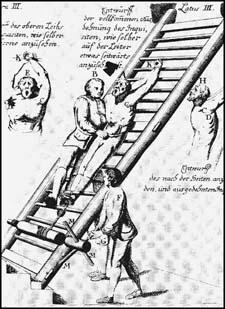

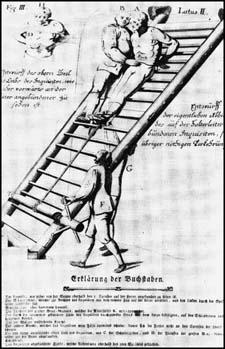

RACK

The rack is such a ubiquitous instrument of torture that it hardly needs any introduction. Consisting of nothing more than a flat, wooden bed on which a prisoner was laid out, the pain was inflicted by tying the victim’s feet to one end of the device and their hands to ropes wound around a large windlass located at the other end. As the windlass was turned, the rope was cranked in, stretching the victim’s limbs to the point where the arms could be dislocated from their sockets and/or the spine disjointed. If torture on the rack was administered carefully, in small sessions of only ten or fifteen minutes at a time and not more than twice a day, the punishment could continue almost indefinitely.

The ladder.

Supposedly, the rack was introduced into England around 1420 by the then Constable of the Tower of London, the Duke of Exeter, and for centuries it was commonly known as the Duke of Exeter’s Daughter. Where the Duke picked up the idea is unknown, but use of the rack throughout the late Middle Ages was as ubiquitous as drinking beer. In France it was known as either

le chevalet

or

le Bane de Torture

; in Spain it was the

escalero

and in Germany the

Ladder

.

The ladder.

Similar to the rack was the German torture popularly known as ‘

Schlimme Liesl

’ (Fearful Eliza). In this instance there was no wooden bed; rather the prisoner’s feet were chained, or tied, to iron rings embedded in the floor while his hands were bound and pulled upward by means of a rope and pulley. In order not to waste a conveniently exposed back, punishment on this vertical rack was frequently accompanied by a severe whipping.

Tearing apart by horses.

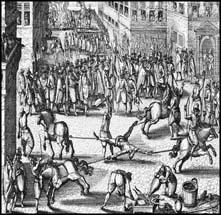

TORN APART BY HORSES

A person is attached to four horses, one to each limb of the body. The horses are then made to gallop in opposite directions in the aim that the person will become dismembered. Not a very effective method unless certain tendons in the limbs are pre-cut. If they are not, then this torment would work in a way akin to the rack, simply stretching and dislocating the joints. Often an executioner would assist in the dismemberment by using a sword or an axe to cut through flesh and tendons and as such, the pull of the horses would literally tear the victim apart. (See illustration.)

BOILING

How far in the past the first poor soul was boiled alive as punishment for their crimes is unknown and unknowable. The effects of boiling water (or oil or other substances) must have been obvious since the day when the first Neolithic cook inadvertently shoved their hand into a crock of boiling soup – the possibility of subjecting enemies to the same pain would have been instantly apparent. Records exist showing that the ancient Assyrian king, Antiochus Epiphanies, boiled Hebrew captives and the Romans boiled Christians in public displays of unimaginable cruelty commonly known as ‘the games’. In 1531, England’s Henry VIII passed a special statute declaring boiling to be the execution of choice for poisoners. This came about when the Bishop of Rochester’s cook, Richard Roose, attempted to poison seventeen members of the Bishop’s household. According to the records, it took Roose more than two hours to die so we can assume that he was not simply thrown into a cauldron of boiling water, but placed in a tepid bath only to have the temperature raised slowly. The Japanese took a slightly more leisurely approach to scalding their victims; they doused them with buckets full of boiling water, one at a time, over a period of days. An account from 1662 tells us that a number of Japanese converts to Christianity were killed in this manner as part of a larger mass execution.