The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History (19 page)

Read The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History Online

Authors: Daniel Diehl

Inevitably, word of such horrific goings-on filtered back to Rome and the Pope. Sixtus was outraged, and sent a letter to King Ferdinand.

Many true and faithful Christians, because of the testimony of enemies, rivals, slaves and other low people – and still less appropriate – without tests of any kind, have been locked up in secular prisons, tortured and condemned like relapsed heretics, deprived of their goods and properties, and given over to the secular arm to be executed, at great danger to their souls, giving a pernicious example and causing scandal to many.

Ferdinand applied political pressure on His Holiness, the Pope relented, and the inquisition continued its deranged crusade against evil-doers.

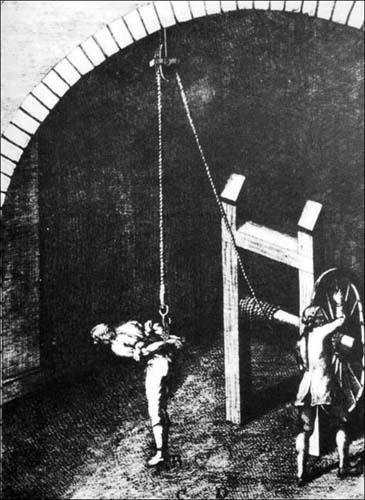

One of the inquisition’s favourite forms of torture was known as the

garrucha

– the torture of the pulley. In this exercise in pain, the victim’s hands were tied behind their back and a rope run from their wrists through a pulley suspended from the ceiling. When the rope was hauled in the prisoner was lifted into the air as their shoulder joints were slowly dislocated. After being left to swing for an appropriate spell, the rope could either be released all at once, sending the prisoner crashing to the ground, or only a few feet at a time, jerking again and again at the arm sockets. If this failed to elicit the desired response, the entire exercise would be repeated with a heavy stone tied to the prisoner’s feet.

Occasionally, the outside world got an inadvertent peek into the inner workings of the Inquisition. When a goldsmith named Lawrence Castro went to the house of inquisitor Don Pedro Guerrero, he was invited on a tour of the good Don’s house, a part of which included the inquisitorial chambers. In the cellars, Castro passed one iron-bound door after another, hearing the muffled screams and moans of the prisoners beyond. When he was about to leave, Don Pedro asked him how he had liked the house; Castro replied that from what he had seen and heard it seemed like the mouth of hell. That was offence enough. For insulting the Holy Inquisition, Castro lost all his property, was whipped through the streets, branded on the shoulders and condemned to be worked to death as a galley slave.

The victim’s wrists are tied behind his back, a rope is attached to the wrist restraints and the sufferer is hoisted up high. At once each humerus is pried out of its joint with the scapula and clavicle, an injury that results in horrendous and permanent deformations of the breast and back. The agony can be heightened by means of weights (such as the one shown here) progressively attached to the feet, until at last the skeleton is pulled apart as it is by the bench and ladder racks. The victim is finally paralysed, and dies.

Although most of the inquisitional tortures we have examined so far were unimaginably painful, the instruments of torture were fairly mundane. On occasion, as time and money allowed, the inquisition came up with some of the most complex and grotesque torture devices imaginable. There is an account of a device much like a giant drum into which a prisoner could be shoved. The inside of the drum was fixed with chunks of razor-sharp iron which would, when the drum was rotated, flay the hide from the victim.

There are reports of giant roasting pans into which hapless victims would be thrown before being slid into an oven and roasted like a side of beef. Such roasting might also be limited to certain parts of the body. In a torture known as the ‘Spanish Chair’, the victim was strapped to a chair while their feet were locked in a pair of stocks, next to which stood a red-hot brazier. To keep the poor wretch’s feet from burning too fast, they were constantly basted with grease. There was, of course, always the old reliable rack for separating a person from both their information and limbs, but next to these more creative punishments the rack seems mundane.

Eventually, if they had not died under interrogation, the prisoner would confess to any charge the inquisitor cared to levy against them. At this point they were bound over for trial. Trials, like hearings and questionings, were carried out in private. The court, like the torture chamber, was likely to be hung with black drapes and buntings; the only ornament in the room being a large crucifix – whether this was to remind the condemned that this was an official church proceeding or to show them how they were likely to end up may be open to question. When a bailiff appeared and shouted: ‘Silence, silence, silence; the Holy Fathers are coming!’, the robed inquisitorial tribunal entered and took their seats, the head inquisitor ringing a small, silver bell to indicate that the proceedings had begun. The defendant had no advocate to speak for them and while the prosecution could call women, children, other condemned heretics, Jews, Moors, slaves and criminals to testify against the accused, the defendant could only call adult, Christian males – not that many people were willing to risk joining the condemned in the docks. Anyone who refused to give evidence when called, gave evidence contradictory to the prosecution’s predetermined game-plan, or reversed their testimony was subject to being sent to the torture chambers to have their memory refreshed.

Chillingly, if a condemned person denounced a sufficient number of their friends to the inquisitors, they might well find themselves absolved of all charges and accepted back into the bosom of the Church. Lesser degrees of cooperation might bring a sentence of a few years to a few months in the dungeons; not many survived such a stretch, but it was better than being burned at the stake. But all it took to avoid one unspeakable fate or another was to admit guilt. The guilty were still burned, but they were given the consolation of knowing that they would be strangled to death before being consigned to the flames. Strangulation by means of a leather strap threaded through small slots cut into the back of a chair was a conventional means of execution in Spain, and was simply adopted by the inquisition as a matter of convenience. From beginning to end Spanish Inquisitional trials were nothing short of a grotesque mockery of both justice and religion.

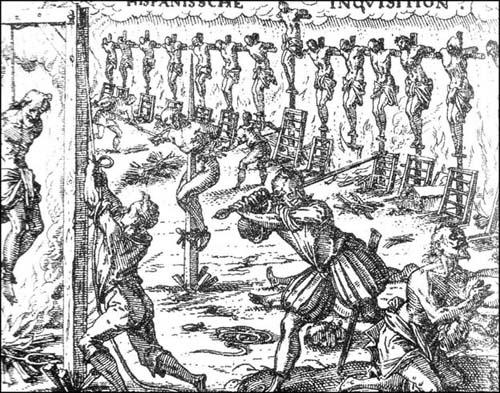

Following their trials, the condemned would take part in what is known as the

auto-de-fe

, a public celebration of the power of the Inquisition over the malign forces which Satan had loosed on God’s world. Most

auto-de-fe

s were held on some public holiday to ensure that they would draw the largest possible crowd – thousands of spectators watching thousands of victims being publicly humiliated before being horribly murdered. In the great parade that opened the official ceremonies the inquisitional monks would parade through the crowd. Following them were the penitents (those found innocent), dressed in black and carrying huge candles as a sign of their renewed faith. Next came the reformed who had, by whatever means, escaped the flames; on the back of their black gowns were sewn inverted flames. Then came those about to die – the flames on their backs were shown pointing upward. This last group is closely guarded by soldiers and members of the Jesuit order who extolled them to last-minute repentance. Finally came the inquisitors mounted on mules and the Inquisitor General riding a white horse. It was not uncommon for the condemned alone to number in the thousands.

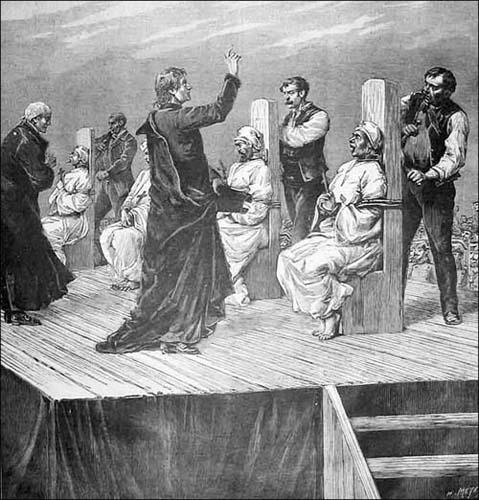

After the prescribed chants had been sung, a priest mounted a scaffold, read out the sentence and symbolically handed the condemned over to the secular authorities, hypocritically pleading with them not to harm these poor lost souls in any way. The victims were then led away for as long as it took for the civil authorities to review their individual cases. An hour or two was usually sufficient for several thousand judicial reviews. They were then paraded back into the courtyard and asked in what religion they wished to die. Those who professed that even after being tortured beyond human endurance, they remained good Catholics were strangled before being tied to the burning stake. The remainder were burnt alive. When the victims had been tied to the stakes, the crowd screamed: ‘Let the dog’s beards be made!’ and anyone wearing a beard (mostly the Jews) had a flaming torch shoved in their face, burning away their beard and charring their face black. Finally, the pyres were lit and over the next hour the condemned died, shrieking and screaming, the fat oozing through their charred and cracking skin, their hands and feet reduced to blackened stumps while they still lived.

As though it were not enough that Spain inflicted this disease on its own people, throughout most of the sixteenth century the Low Countries (Belgium, Holland and the Netherlands) were under the fanatical control of the Spanish crown and they, too, were subject to the Spanish Inquisition. Between 1568 and 1573 roughly 18,000 Dutch men and women were executed by the Inquisition, mostly for adhering to the Protestant faith. Many were burnt, some were drowned and some buried alive. Impossible as it is to believe, the Spanish Inquisition did not cease in Spain until 1808 when Spain was invaded by the armies of Napoleon Bonaparte and, despite the fact that in 1816 the Pope flatly forbade inquisitors from forcibly extracting confessions, torture was not formally abolished until 1821. Between 1481 and 1808 more than 33,000 Spanish men, women and children were burnt alive and more than 290,000 were tortured and imprisoned with the loss of all their property. How many thousands may have died under torture remains unknown. During the seventeen years he spent as Grand Inquisitor, Thomas de Torquemada, alone, sentenced upwards of 10,000 to the burning stake and 100,000 to imprisonment. One can hope that during the more than three centuries of the Spanish Inquisition’s existence the rest of the world managed to drag itself out of the mire. How well they achieved this goal will be examined in the following chapter.

There are two basic versions of this almost legendary instrument: (1) the typically Spanish one in which the screw draws back the iron collar, killing the victim by asphyxiation alone; and (2) the Catalonian one, in which an iron point penetrates and crushes the cervical vertebrae whilst at the same time forcing the entire neck forward and crushing the trachea against the fixed collar, thus killing by both asphyxiation and slow destruction of the spinal cord. The agony can be prolonged according to the executioner’s whim.