The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History (20 page)

Read The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History Online

Authors: Daniel Diehl

In this image of an

auto-de-fe

courtesy of the Spanish Inquisition, we see an entire row of heretics being burned in the background, while the foreground shows us (from left to right): a man being slowly roasted over a fire (for what purpose we can only guess); an impaling (presumably the variation in sentence being linked to the variation in ‘crime’) and a comparatively merciful beheading by the sword.

Here we see another mass burning. This woodcut depicts the burning of twenty-three Jews convicted of the murder of Christian children for the Passover rites – a charge trumped up against Jewish communities all over Europe and always ‘proved’ with the methods that were applied to witchcraft and heresy trials. Once the Torturers elicited the confession they required, that confession was used as ‘proof’ for the condemnation of others.

T

he period between 1600 and 1700 is often called the Age of Reason. This may be an appropriate enough term when referring to the scientific advancements of the period, but in the field of juris prudence and corporal punishment things remained pretty much business as usual. When Queen Elizabeth I died in 1603 she was succeeded on the throne of England by her second cousin, King James VI of Scotland. Having already spent eighteen years on the Scottish throne, the thirty-nine-year-old monarch had no intention of changing the way he did things, and the accepted ways of doing things in Scotland were even harsher than they had been in England under the Tudors.

Of all the things James was afraid of, and there seem to have been an over-abundance of them, one of his most deep-seated fears was of witchcraft. In 1590, while still on the throne of Scotland, he had ordered the arrest of one Dr Fian (alias John Cunningham), along with forty accomplices, on charges of sorcery and trying to kill King James by bewitching him to death. There is no doubt that Cunningham was a dangerous and foolish man; he openly styled himself as a magician and was long suspected of dealing in poisons, so James’ subordinates had ample reason to believe that if, indeed, there was a plot against the king, Cunningham was probably involved. In an effort to extract details of Cunningham’s evil doings the royal torturers ripped off his fingernails and drove needles into the bleeding flesh of his finger tips.

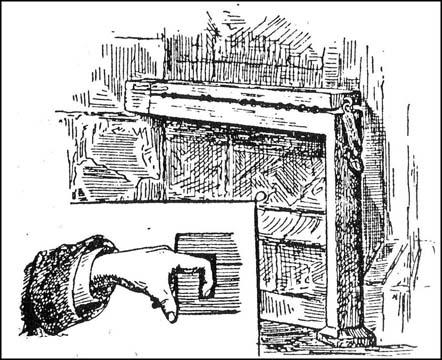

When that failed to elicit a confession, the good doctor was subjected to the ‘boots’, a device in which his lower legs were so horribly crushed that blood and bone marrow oozed from the edges of the iron shoe. Still, the stalwart Cunningham refused to confess but his denial failed to save him. He was strangled and his body burnt at the stake. The following year, 1591, another Scottish ‘witch’ had her fingers locked in a clamp-like device called the ‘pilliwinckes’ while her head was lashed with ropes and jerked violently back and forth. Finally being identified as a witch by a ‘witch’s mark’ on her throat (probably a mole, wart or birth-mark, commonly known to witch hunters everywhere as a

stigmata sagarum

), she confessed and was executed.

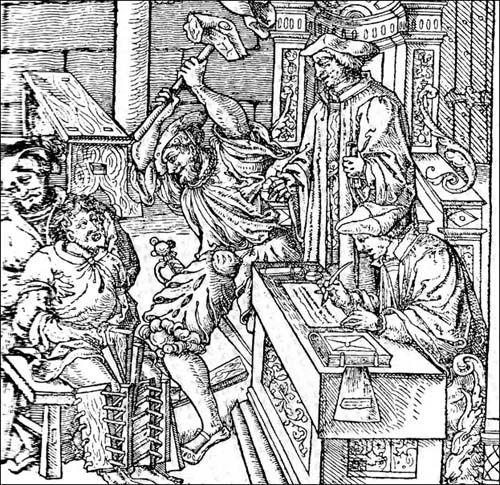

Here we have an illustration of the inquisitorial process at work. The victim is enduring the torture of the brodequin. A wooden framework encases his legs from the knees to the ankles while wedges are hammered in with a large mallet until all of the bones in his knees, lower leg and ankles have been broken. This would be deliberately slow and painful, but also intentionally non-lethal and not too shocking, sudden or overwhelming to cause the victim to faint. He is being continually questioned about his supposed ‘crimes’ and the scribe is dutifully recording his responses.

Obviously these tortures were not only in accordance with accepted practices of witch hunting, but also in line with King James’ own thoughts on the subject, all duly recorded and expounded upon in a book entitled

Daemonology

. Just how hell-bent on rooting out witches in Scotland James was, was best expressed by a contemporary Edinburgh jurist when he said: ‘An old wife circumstantially accused of witchcraft at a Galloway kirk-session [church service] has as little chance of mercy as a Jew before the Spanish Inquisition’.

Naturally, when James came to the throne of England, neatly tucked away among his baggage were all his fears and superstitions against those who made pacts with the Devil, and he quickly enacted laws making it a capital offence to ‘feed or reward any [evil] spirit, or any part of it, skin or bone’. At James’ behest a special act was passed against ‘Conjuration, Witchcraft and dealing with evil and wicked spirits’.

An example of the pilliwinckes or finger pillory in the church of Ashby-de-la-Zouche in Leicestershire, England. Such devices were instilled in great estates everywhere probably as a punishment for thieving servants, but those which were in churches might also be employed to publicly shame penitents before the congregation.

There were other high crimes and misdemeanours rampant in England as well as witchcraft and James had to deal with these as well; some of the punishments he decreed were bizarrely tailored to suit the particular crime. A first-time arrest for drunkenness was met with a simple fine of 5

s

, but subsequent arrests on the same charge would condemn the inebriate to wear a ‘Drunkard’s Cloak’ – a beer keg with one end knocked out and a hole cut in the other large enough for the miscreant’s head to fit through. The man was then condemned to wear this humiliating costume in public for a proscribed period of time. Considering that a cask large enough to fit over a man would weigh as much as the man himself, it would have been a terrible experience. The Drunkard’s Cloak must have become a standard punishment because there are records of it still in use as late as 1690.

In other instances of making the punishment fit the crime, a Jew convicted of being a heretic was sentenced to prison where he was kept on a diet of pork; and false witnesses and perjurers were forced to wear a tongue-shaped piece of red cloth sewn to their clothes.

More serious were the punishments and tortures meted out to those suspected of treason. In 1604, during King James’ second year on the throne, Guy Fawkes and a gang of Catholic plotters were discovered to have buried more than two dozen kegs of gunpowder under the houses of Parliament. James ordered that Fawkes was to be questioned rigorously and: ‘If he will not otherwise confess, the gentlest tortures are to be first used on him, and so on, step by step, to the most severe, and so God speed the good work’. What ‘gentle’ tortures were applied to Fawkes is unknown, but before being tried and executed along with his companions he was racked mercilessly. While hanging, drawing and quartering had gone out after the Babington plot during Elizabeth’s reign, Fawkes and his companions’ carcasses were publicly hacked to pieces after they had been hanged.

A species of pillory inflicted for the most part on chronic drunkards, who were exposed to public ridicule in this fashion. The ‘drunkard’s cloak’ could take one of two primary forms: those closed on the bottom, with the victim immersed in faeces and urine, or merely putrid water; or else open, so that the victim could walk and be led about the town with the enormous and very painful weight on his shoulders.

The victim of this device would be ‘prolonged’ by force of the winch, and various sources testify to cases of thirty centimeters or twelve inches, an inconceivable length that comes of the dislocation and extrusion of every joint in the arms and legs, of the dismemberment of the spinal column, and of course of the ripping and detachment of the muscles of the limbs, thorax and abdomen – effects that are, needless to say, fatal.

Hanging, that long-established and wildly popular form of public entertainment, was given greater standardisation under King James. No longer would hangings in London take place wherever seemed convenient at the moment. Henceforth they would all take place at Tyburn – located near the spot where London’s Marble Arch now stands. If you are going to host a public spectacle it is nice if people know where to find the show; and hangings at Tyburn were nothing less. Bleachers were built to accommodate the crowds and seat prices varied according to how close to the victim you wanted to sit and how important a personage the condemned happened to be. Along the route from the prison to Tyburn, the cart bearing the condemned first stopped at a church where a priest begged the condemned to repent. Next stop was the Hospital of St Giles-in-the-fields where a last mug of ale was offered to the soon-to-be departed. Sometimes, if a simple hanging was deemed to be too good for the villain, he was wrapped in chains, or locked in the human-shaped, iron cage known as a gibbet, and allowed to swing in the breeze until he died of exposure and thirst. Occasionally a sympathetic passer-by would put a bullet through his head and end his suffering but just as often they were used for target practice.