The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History (8 page)

Read The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History Online

Authors: Daniel Diehl

Antiochus took exception to all this; after all, all he wanted was for the Jews to become docile slaves like the rest of his vanquished empire. It seemed obvious to Antiochus that what the Jews needed were a few graphic examples of just how powerful their new king was, and how silly their own beliefs were. Particularly galling to Antiochus was the Jewish dietary law which forbade the eating of pork. In one instance, a boy who refused to eat pork was tied to a wheel where his joints were dislocated, his bones broken and his flesh torn with red-hot pincers. A bed of coals that had been built beneath the wheel, to increase the boy’s pain, was extinguished by the boy’s own, flowing blood. On another occasion, seven brothers and their aged mother were hauled before Antiochus for the same offence. The king assured them that their God would understand if they ate pork under duress and forgive for the sin, pointing out that if they refused to eat, they would all be horribly executed in front of their mother. Neither the lads, nor their mother, were having any of it. After the eldest boy had been broken on the wheel and his limbs had been cut off, the king said he would reprieve the remaining six boys if they would share a succulent pork dinner with him. Again they refused. The second youth had his limbs severed and his still-living trunk cooked in a gigantic frying pan. The third brother was skinned alive and disembowelled, the fourth had his tongue ripped out before being roasted alive on a spit and the fifth was burned at the stake. When the sixth was tossed into a cauldron of boiling water, the youngest simply threw himself into the cauldron to die with his brother. Frustrated, Antiochus accused the mother of forcing her sons to their deaths by not permitting them to transgress against their religion, and sentenced her to be burnt alive. By 63 BC the Maccabeean revolt had collapsed and the Jews remained stateless, but the power of the Assyrians was also waning. A new, more advanced civilization had taken centre stage in the world, and with them they brought new and more advanced forms of torture.

The Classical Greeks were a civilised people. Well, they certainly believed they were, and we generally accept it as fact. As early as 1179 BC there were Greek laws prohibiting murder but, in a typically enlightened way, a death sentence could only be passed by an officially sanctioned court of law. This would seem to have been a good start, but unfortunately things went rapidly downhill from there. In the decades around 700 BC the Tyrant Draco (Tyrant then being an official title as was Dictator) decided that if a little capital punishment was good then a lot of it would be all that much better. Thus he declared that administering the law would become vastly easier if there was only one punishment for all crimes – death. Everything from stealing a loaf of bread to murder was punished by death. When asked why he imposed such a law, Draco quipped: ‘The poor deserve to die and I can think of no greater punishment to inflict upon the rich’. Draco – which, interestingly, translates as ‘serpent’ – may not have lasted long, but his name is still attached to harsh laws, or measures, in the term ‘draconian’.

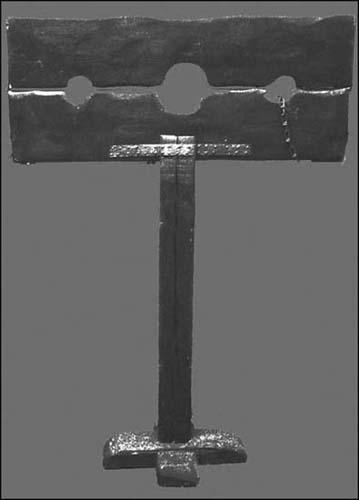

Most readers will be familiar with this device. Far more than being a simple mode of imprisonment, it served to trap the victim’s head and hands in a position where they could not protect or defend themselves against assaults, thrown objects or molestations by the jeering populace of the city.

The Greeks, in general, seemed to have had a difficult time striking a happy medium in their judicial system. Three and a half centuries after Draco, the Athenian lawgiver Charondas came up with a slate of laws known as the Thurian Code. We are not here to take issue with the code itself – which was the basic ‘eye for an eye’ approach to juris prudence common among early societies – but rather with how it was administered. In order to prevent any ambitious reformers from arbitrarily altering his new laws, Charondas decreed that anyone proposing a change to the code would be forced to wear a noose around his neck until the matter was fully debated among the assembly of lawgivers. Should the change be rejected, the man was to be immediately strangled with the noose already so conveniently in place. It is hardly surprising that while Charondas remained in power only three such changes were proposed. Worth mentioning is the fact that even the hard-nosed Charondas was completely dedicated to adhering to his laws. When he inadvertently appeared at a public assembly wearing a sword (an act outlawed by the Thurian Code) he drew the offending blade and plunged it into his own heart.

In their more enlightened moments, the Greeks introduced some of the first punishments designed to cause no physical harm to the convicted. Among these was the pillory, a device still in common use at the end of the eighteenth century, in which the condemned had their head and arms locked into a wooden frame mounted on a pole. It was an uncomfortable thing, no doubt, and made all the more so by the fact that the malefactor was displayed in a public place and subjected to the taunts and harangues of passers-by, but there was no long-term damage to their body (at least not any inflicted by the pillory itself). The most common offence which led to the pillory was public drunkenness. Curiously, when an individual committed a crime while drunk they were charged and tried twice – once for being drunk and a second time for the associated crime. Evidently the Greek legal system did not necessarily agree with Aristotle when he said: ‘

In vino veritas

’ – ‘In wine there is truth’.

Here we witness an unfortunate victim being stuffed within the brazen bull and a great fire being lit beneath. This would of course function much like a cast bronze oven and would quickly become unbearably hot to touch. The howls and screams of the roasting culprit would be heard to issue forth from the mouth of the bull like snorts and grunts, much to the amusement of the torturers and assembled court.

Not all Greek tortures were designed as punishment and the use of torture to extract confessions may well have originated in Classical Greece. To this end they employed both the rack and a version of the wheel. In Greek wheel torture, the victim was simply tied to a cart wheel and spun around until they offered up the required information. More severe ‘turns’ on the wheel could, and often did, lead to death, probably through asphyxiation, choking on one’s own vomit, cerebral haemorrhage or heart attack. Surprisingly, even such ‘enlightened’ Greek philosophers as Aristotle and Demosthenes were fully in favour of torture as a means of obtaining information. Aristotle wrote that he approved of such methods because they provided: ‘a sort of evidence that appears to carry with it absolute credibility’. Evidently he failed to consider the fact that almost anyone will confess to anything if subjected to enough pain. One wonders what Aristotle might have thought of that ingenious Greek device known as the ‘Brazen Bull’?

The Brazen Bull was supposedly invented by a man named Perillus in an attempt to curry favour with the dictator Phalaris of Agigentum. The device was no more than a hollow, life-sized bronze figure of a bull with a door in one side and holes at its nostrils and mouth. In application, a person convicted of a capital crime was stuffed into the bull, through the door in its side, and a blazing fire was then lit beneath the statue. As the bronze heated to red-hot, the victim’s screams echoed from its nostrils and mouth, much like the cries of a maddened bull. While he seems to have been delighted with the device itself, Phalaris had no time for fawning sycophants and promptly condemned Perillus, its inventor, to be its first victim. Evidently Phalaris’ subjects had no more time for their dictator than he had for Perillus. After enduring all they could of his tyrannies, in the year 563 BC, the mob stuffed the dictator himself into the Brazen Bull.

Classical Greece had no coherent political system. Rather, it was a collection of culturally diverse and geographically scattered city states; some of which, like Athens, were a bit more civilised than others (such as Agigentum over which Phalaris ruled). The more remote and less civilised of these city states seemed to invent impossibly creative tortures. According to Greek historian Lucian, on one occasion a young woman was sewn inside the carcass of a freshly slaughtered donkey with only her head remaining exposed. As the Mediterranean sun beat down on the victim, the carcass shrank and began to rot. In addition to the tortures of hunger, thirst and exposure, as the carcass decomposed it attracted worms and insects which attacked the flesh of the victim as well as the carcass of the animal. How long the victim survived is not related. Another similarly grim torture comes from the pen of Aristophanes. In this account, the condemned was locked in a pillory and smeared with milk and honey as an enticement to insects. If he managed to survive hunger, thirst, exposure and insect attacks for twenty days, he was released. That is to say, he was released in order to be hauled to a cliff and thrown to his death.

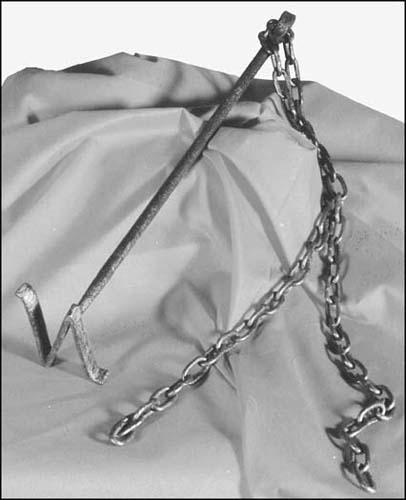

This is an example of a branding iron of the type which would have been used on Spartan males found guilty of being dedicated ‘bachelors’.

Among the more hardy and individualistic of the Ancient Greeks were the Spartans. Tough, bold and decidedly war-like, the Spartans had no time for the soft-living ways of people like the Athenians. If a Spartan man became overly fat, he was publicly whipped; if he remained unmarried for too long (and thereby suspected of preferring men to women) he was publicly branded with a hot iron. The Tyrant Nabis, who ruled Sparta from 205–194 BC, invented a very personal, and personally amusing, means of torturing those who annoyed him. It seems that Nabis commissioned an iron statue in the shape of his wife, Apega. This statue was built so its arms would open on hinges, the inner face of the arms and chest being set with numerous, long, sharp spikes. When Nabis personally questioned an accused malefactor and did not like the answers he got, he is said to have quipped: ‘If I have not talent enough to prevail upon you, perhaps my good wife Apega may persuade you’. One fatal embrace from the iron Apega may have ended the interrogation, but Nabis enjoyed his little jokes.

The Greeks, like the Babylonians and Assyrians before them, eventually went into decline, to be replaced by a newer and more efficient culture; in this particular case, it was the Romans who became the dominant power in the area. Roman civilisation, and its associated views on torture, must be divided into two distinct categories; the first being the Roman Republic and the second the Roman Empire (the periods before, and after, Julius Caesar).