The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History (12 page)

Read The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History Online

Authors: Daniel Diehl

Such grotesque public displays were not the sole province of England. Even such an exalted personage as Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV, when excommunicated by the Pope, travelled to Rome, lay face down in the snow for two days, praying and fasting, until the Holy Father finally relented and forgave him. It did not do much good; in 1105 Emperor Henry was still forced to abdicate. Curiously, as barbaric as these punishments seem, as the Normans’ fierce grip on England relaxed at the dawn of the twelfth century, it was the common people who objected to the demise of trial by ordeal. Even England’s penultimate Norman ruler, Henry I, tried to reform his family’s harsh, earlier laws, relying more on prisons and short turns in a dungeon than on corporal punishment. Simultaneously he increased the number of capital crimes. By 1124 death had become the standard punishment for murder, treason, burglary, arson, robbery and simple theft, and more and more people convicted of lesser crimes were simply being detained behind bars for various lengths of time. It is hardly surprising that during the protracted Civil War (1139–1148) between England’s King Stephen and his cousin, Empress Matilda, the dungeons of England overflowed and by 1155 London’s first purpose-built prison, The Fleet, had been erected by the new king, Henry II.

It is worth noting here, that the central fortified secure tower of a castle was known as a ‘keep’ in English, but as all of the castles in England were owned by the Normans at this period, they were frequently referred to by their Norman French name, ‘donjon’, from which the term dungeon is derived.

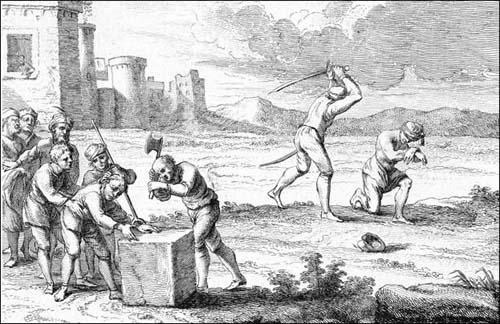

The unfortunate culprit on the left-hand side of this image is about to have his left hand chopped off. Corporal punishment such as this dismemberment was commonplace throughout medieval Europe for petty crimes, while the capital punishment on the righthand side of the image was reserved for somewhat more serious offences.

As Henry (the French-born son of Empress Matilda) was an outsider to England, he was not made to feel any more welcome than the Normans had been a century earlier. Rather than ‘harry’ his new kingdom, however, he filled it with prisons. Every town and borough was ordered to have some kind of prison facility – preferably inside a nice, secure castle – and these were to be used, in Henry’s words, ‘to confine tight, presumptive evil-doers’. This meant that anyone accused, or suspected, of a crime was to be locked up until the circuit judge showed up and then returned to the cells to serve their sentence. Henry also proved himself just as fond of maiming his subjects as William the Conqueror had ever been. Murder, armed robbery and counterfeiting were all punishable by having the right hand cut off. Giving in to local demands for gaudy judicial displays, he allowed trial by ordeal for any crime worth less than 5

s

; but those found guilty were not executed. Instead, they had a foot hacked off. It would take more than a century before trial by ordeal was finally abolished throughout Europe, and then only because Pope Innocent III refused to allow the clergy to assist in such divine judgments. In 1215, the same year Pope Innocent forbade the clergy from taking part in trials by ordeal, King John of England was forced into signing the Magna Charta, the closest England had ever come to a written constitution. In the Magna Charta are specific prohibitions against the use of torture and any and all legal procedures that may involve torture as being contrary to the basic concept of English Common Law. Curiously, both the abolition of trial by ordeal and the signing of Magna Charta did nothing more than throw the entire English and European legal systems into a tail-spin. Without the presence of a priest, trial by ordeal did not have the sanction of God and without trial by ordeal, how could God’s will, and the truth, possibly be discovered? Judicial torture may not have involved God’s will, but without the threat of torture, how could guilt ever be satisfactorily proven? It was not an enlightened age but there were voices of reason popping up here and there. In far-off Germany, Abbess Hildegarde von Bingen (1098–1179, now known as St Hildegarde) not only spoke up in favour of leniency toward those convicted of capital crimes, but even defended the un-Godly, when she insisted that those convicted of heresy should not be executed. Sometimes, voices of reason are heard, even if only temporarily.

This somewhat comical image shows what appears to be a poet or balladeer (based on the lute hung upon the post) who has probably been sentenced to the stocks for seditious verses. How frustrating it must have been to see the dog making off with his stash of food from his satchel so tantalizingly out of reach. But this is of course nothing when compared to the other tortures endured by his contemporaries.

England was already moving away from the cruellest forms of mutilation and execution and toward public humiliation that marked criminals as social pariahs without causing them any permanent, physical damage. The public aspect of punishment was important because people demanded that they be allowed to witness a criminal’s punishment – how else could they know that justice had been served? Toward this end, the stocks were introduced.

Less physically painful than the pillory, the stocks only locked a person’s feet in a wooden frame, the rest of their body remained free. To make this a punishment rather than just an afternoon in a public place, the convict was forced to sit on the narrow edge of a board with their legs extended in front of them and locked in the stocks. Thus secured, they were still subjected to taunts and thrown objects, but could at least fend off large objects and rocks with their arms. Still, the stocks were humiliating and seemed to satisfy the demand for public punishment. This new concept in punishment seemed so enlightened that at one point, the entirety of the House of Commons knelt and prayed that stocks would be erected in every town and village in England.

Other forms of punishment for all manner of offences were also popular. Among these was the custom of ‘outlawing’. Declaring a person an outlaw (specifically meaning that the guilty party was to remain at large but were no longer afforded any protection by the law) had been introduced by the Normans, but, for several reasons, became more popular as time went on. First, it cost nothing to declare a person an outlaw and, second, it was immensely profitable for the government. An outlaw lost not only the title to his, or her, land but forfeited all personal possessions and wealth to the crown. Further, as the convicted was no longer under any form of legal protection, they could be murdered by anyone, at any time, without any consequences. An idea of just how popular a practice this was can be seen by a quick look at the judicial records for the county of Gloucestershire, England for the year 1221. Of 330 cases of murder tried that year, only fourteen of the convicted were hanged while 100 were declared outlaw and turned loose; the remaining 216 either being given alternative sentences or found innocent of the charges. Outlawing may seem like a relatively easy punishment, but consider that when a man was executed for a crime his family retained the rights to his estate, if he was declared outlaw, they were dispossessed when the land reverted to the government.

Playing on this easy method of accumulating land and money, in 1255 King Henry III outlawed more than seventy murderers, adding whatever wealth they had to his own coffers. The next year, out of seventy-seven suspected murderers five were acquitted and seventy-two were outlawed. In 1279, the Northumbrian courts heard sixty-eight cases of murder, released four of the accused and outlawed the rest. Outlawry was good business, not only for the courts, but for the convicted. If an outlaw discovered evidence that would clear them, they could apply to have their case retried. Should the new evidence convince the judges, the convict would have his sentence revoked. Of course this made him, or her, essentially a new person, and therefore not entitled to reclaim any property which may have been the possession of the ‘old’ person; but at least they had their life back. Other crimes that had once been punished by harsh, physical tortures were also treated in a humiliating but harmless manner. Bakers found guilty of selling loaves smaller than regulation size, or of adulterating their flour with chaff, sand or sawdust were either displayed in the stocks or dragged through the streets of town on a section of woven fence (known as a hurdle) with a loaf of bread tied around their neck. It may not have been the best advertisement for their business, but it was a lot less grim than having a hand chopped off.

This is an example of a baker’s cart. There were many variations on this punishment. A baker, having been found guilty of selling underweight loaves of bread or of ‘weighting’ his loaves with the inclusion of sawdust, etc, would be chained to this cart filled with heavy weights and be paraded through the streets with a loaf of bread around his neck. Baker’s guild ordinances tried to mandate against such ‘mistakes’ and frequently, in an effort to avoid this outcome even accidentally, we find that bakers would give an extra loaf of bread away for free with every dozen purchased (just in case there was any shortfall). This then, is the origin of the baker’s dozen.

This is not to assume that harsh, and sometimes grotesquely novel, punishments did not take place in the realm of England. In 1241, Henry III – that otherwise enlightened monarch, more concerned with making a fast buck than torturing his subjects – introduced the highly creative form of terminal torture known as being hanged, drawn and quartered. The victim was first pulled from the ground by a noose and left to dangle until they lost consciousness. They were then brought down and revived only to be castrated before having their stomach ripped open, their entrails drawn out and tossed onto a fire before their still-living eyes. Only then was the victim’s head struck off, ending their unspeakable suffering. The various bits and pieces of the carcass were subsequently displayed around the countryside as an example to others who might have been contemplating treason. But it hardly seemed to matter what Henry did, be it gentle or cruel, the crime rate skyrocketed. What was needed was a total reformer, a man who cared nothing for what people thought and was willing to whip society into shape at any cost. What was needed was Henry III’s son Edward.

Edward I – also known as Longshanks, Hammer of the Scots and probably a lot less savoury things – ruled from 1272 until 1307 and spent every waking minute (at least those minutes when he was not busy slaughtering the Scots or the Welsh) reshaping the English legal system. He gathered the smartest lawyers and prelates in the realm and augmented their numbers by importing still more lawyers from Rome. Slowly, methodically, Henry and his advisors disassembled the feudal system and built a new system of justice. One of the first issues they tackled was the right of a prisoner to refuse to plead to charges levied against them. Under Edward’s rules, anyone who refused to answer charges were chained, face down, to a dungeon floor and fed a small piece of stale bread one day and given a small cup of brackish water the next. If a week or so of this failed to loosen their tongues, they were pressed beneath an increasing amount of weight; they either lodged a plea or were slowly crushed to death.