The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History (11 page)

Read The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History Online

Authors: Daniel Diehl

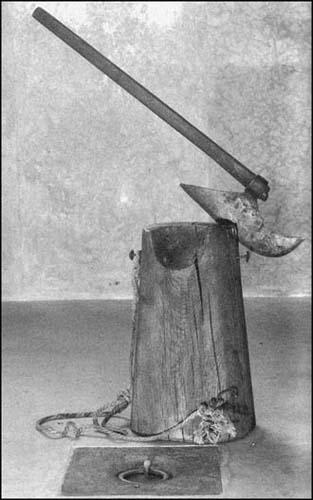

Whether this device was intended to restrain a victim whilst plunging them beneath the surface of a lake or river or was intended to hold them aloft and captive for public display and ridicule is uncertain. It is likely that it probably served both purposes. This fine example can today be found in the Museum of Torture in San Gimignano, Italy.

In an effort to codify, and thereby equalise, the laws of his kingdom, the seventh-century king of Kent, Ethelbert I, became the first English ruler to write down his laws. Like those of his contemporaries, Ethelbert’s laws relied far more on a sliding system of fines (peppered with the occasional public humiliation) than on physical punishment or execution – the need for soldiers to fight off the Vikings was too great to allow the death of any but the most hardened criminals. Women, on the other hand, did not fight and were therefore expendable. Women found guilty of theft or murder were executed. To make his concept of crime and punishment clear, Ethelbert even assigned values to specific parts of the human body and to life itself. Murder was punished by a fine of 100

s

. Should one person cause another to lose an eye, they were to pay the victim 50

s

or an equal value in goods. Should the damaged part be a toenail, the fine was 6

d

; the same fine being imposed if a man’s reproductive organs were damaged. Naturally, the fines increased if the injured party was a person of great social standing: rank hath its privileges. What all this shows us is that the power of the Church (at this period in time at least) played an important part in civilising the laws of those nations that had accepted Christianity. Inevitably, a share of all fines collected as punishment for a crime found its way into the coffers of the local church; a small price to pay for dragging society away from blood feuds and barbaric tortures.

The impact of religion on the justice system also changed the list of acts which were considered socially unacceptable. For the first time, fornication (that is to say, sex outside of wedlock) and adultery both became punishable offences, as did eating meat during proscribed periods of fasting, working on Sunday and worshiping the old (pagan) gods. Predictably, rules governing the clergy were slightly different than those governing laymen and men of the cloth were frequently provided with neat loopholes by which they could escape punishment. The word of a bishop, like that of a king, needed no second-party confirmation to be accepted as fact. If a priest was accused of a crime he could absolve himself by swearing his innocence before the altar. The system may have had its flaws, but it was a vast improvement over what had gone before and, equally, over what was yet to come.

With the death of Alfred the Great, King of the West Saxons, in 901 the trend toward leniency slowly began to reverse itself. It was a lawless time in a lawless world and the general public insisted that criminals be soundly, and publicly, made to pay for their crimes. Within a generation whipping came back into fashion, as did physical mutilation. Capital punishment took on new and novel forms: free men and women were thrown from cliffs; male slaves who stole were stoned to death by fellow slaves (presumably as a hands-on lesson in proper behaviour) and thieving female slaves were either stoned or drowned. For the first time witches were punished, the practitioners of these dark arts being confined to prison for four months – unless they had caused a death by their conjurations, in which case they were executed.

Three-quarters of a century later, King Ethelred tried to reverse this disturbing back-sliding. Late in his reign, around the year 1000, he said: ‘… that Christian men for all too little be not condemned to death; but in general let mild punishment be decreed; and let not for a little God’s handiwork and his own purchase be destroyed …’ Surprisingly, this more lenient policy was adopted by another English monarch of about the same period, King Canute. Canute, a Christianised Viking and King of southern England, Denmark, Norway and parts of Sweden, stated his opposition to harsh punishment with the words: ‘… rather let gentle punishments be decreed for the benefit of the people’. It sounds good, but bear in mind that deep down, Canute was still a Viking and Vikings had a long history of mutilating people. Under Canute’s laws routine punishments included cutting off ears, noses and upper lips: a woman convicted of adultery lost both ears and her nose. Eyes were gouged out and scalping was brought into fashion. To his credit, Canute tried to take all aspects of a person’s life into consideration when judging them, and was notably lenient when the criminal was a teenager, elderly, desperately poor or ill and he took into account whether they were free or a slave – presumably slaves were given less latitude than free men and women. Accidental transgressions were also judged less harshly than premeditated ones. All in all, life under Canute was relatively good and crime was at a low ebb. Sadly, Canute died in 1035 and although his laws survived him by three decades – being made even more palatable by his descendant, the pious King Edward the Confessor – all progress was lost in the autumn of 1066 when England was invaded by a group of ex-Vikings who had recently seized Northern France and begun calling themselves Normans.

Duke William of Normandy was a bastard. That much is an historical and biological fact; it was also an opinion shared by nearly all of his subjects and most of his followers. For nearly two centuries prior to the Norman invasion of England a few continental powers, including the French, Burgundians and Normans, had been following a new political system known today as feudalism. Under the feudal system, great lords owed obedience to the king, knights owed obedience to their lords, the peasants owed obedience to everyone above them and everybody owed obedience to the Church. In theory, feudalism was meant to protect the poor, the helpless and Holy Mother Church. It was a good idea but, like so many good ideas, it went wrong almost from the start. Somehow, when anything unpleasant happened, the peasants were blamed and suffered mightily under the pernicious greed of their overlords. Because the feudal system did not develop in England, but was imposed on it following the Norman Conquest of October, 1066, it is a perfect case study in how the system worked – or failed to work.

Beheading by sword or axe was a public entertainment in central and northern Europe until as recently as 150 years ago. The axe was preferred in Gallic and Mediterranean Europe. A long apprenticeship is needed for perfecting aim and force; executioners kept in trim by practicing on animals in slaughter houses.

William, now known alternately as William the Conqueror and William I of England, treated his subjects like the enemy. To ensure that they would never contemplate revolting he ‘harried’ the countryside. In this case, harrying meant burning the fields, homesteads, villages and towns, leaving the peasants and villagers homeless and starving and creating a famine that lasted a decade. Even William’s own chronicler, Ordericus, was appalled at the devastation. ‘William, in the fullness of his wrath, ordered that the corn and cattle, with all the farming implements and provisions, [were] to be collected on heaps and set on fire.’ To make certain the point was not lost on his subjects, William instituted a program of castle building intended to intimidate any of the English who survived his arrival. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles described this program of public works with the words: ‘He built him castles as a place to annoy his enemies from … And they oppressed the people greatly with castle building’. Obviously, as punishment for losing the war, the English were used as slave labour in the building of the very castles which would ensure their future good behaviour.

Beheading was an ‘easy’ death if carried out with skill and as such was reserved for noblemen. Plebeians tended to be executed by slower, more painful means such as slow hanging. This device, known as a ‘fallbrett’ (literally a falling board) was an ancestor of the guillotine. But unlike its later French descendant, the fallbrett would not remove the head in a single swift stroke, but rather, the wooden ‘edge’ would rip and chew its way through the flesh and vertebrae under the impact of the sledge blows.

Needing all the labourers he could round up, and always believing that lasting, public examples should be made of transgressors, William preferred maiming law-breakers rather than simply executing them. In his inaugural speech, after being crowned king on Christmas day 1066, William said: ‘I forbid that any person be killed or hanged for any cause.’ Then he added: ‘Let their eyes be torn out and their testicles be cut off’. Naturally, the ‘no killing’ part of this speech did not apply if a Norman was killed; in that case, Anglo-Saxon suspects were rounded up and hanged by the score. If one Norman was murdered by another it would have set a bad example for William to execute one of his own people in the same manner as a common peasant, so he devised a death sentence reserved for noblemen: beheading. It was a tradition that would outlive him by centuries.

Being a delicate and chivalrous sort, William never sentenced a woman to the humiliation of the gallows or headsman’s block; for them, the only socially acceptable death was the burning post. For lesser crimes there was also a nice selection of brand-new castle dungeons now available. In a concerted attempt to keep local Church officials out of his way, the king decreed that ecclesiastic courts would, henceforth, only be allowed to try ecclesiastic crimes. Civil cases, which had previously been overseen by Church officials and carried out according to Church law, were now the Crown’s own private domain.

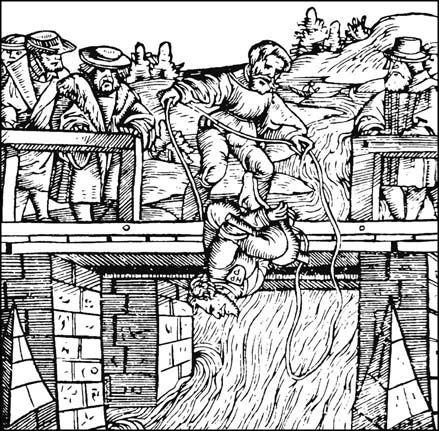

Somehow, all these harsh measures did more to propagate crime than to end it. By the time William’s second son, Henry I (reigned 1100–1135) came to the throne, not only were the old crimes still flourishing, but new ones were being invented every day and almost no witnesses could be found who were willing to testify against anybody. Knowing that he simply could not execute every possible suspect, and neither could he allow every miscreant to escape punishment, Henry decided the best thing to do was to let God decide guilt or innocence and, after convincing the Church to support him, he re-instituted trial by ordeal. There was trial by water (in which the suspect was thrown into a pool and if they sunk were deemed innocent), trial by fire (in which the suspect had to grab a hot iron bar while he walked nine paces and prayed that no blisters appeared after three days) and trial by fire and water (in which the suspect plunged their hands into a cauldron of boiling water, picked up a stone and again prayed that no blisters developed). For priests accused of civil crimes these particular atrocities were replaced with the ordeal of coarsened bread, in which the accused was made to eat bread containing feathers; if they choked, they were presumed guilty.

Here we see the accused has had his hands bound to his ankles and is being thrown off a bridge in the fast flowing currents of the river below. This is a version of the trial by ordeal. If the water rejects him (he floats) then he will be declared guilty by his accusers. But if the water accepts him (he sinks to the bottom) he will be judged innocent and presumably hauled out of the water by the attached rope. How many individuals were found innocent but died as a result of this method of assessment is unknowable.