The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History (9 page)

Read The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History Online

Authors: Daniel Diehl

While we do not have an actual depiction of Apega, this image of the Iron Maiden of Nuremburg should serve to illustrate the dangerous result of her cold embrace. There were various versions of this device. Some of which were designed to be lethal, and some were merely intended to be injurious.

Early Romans, like the Greeks whose culture they co-opted, tried to construct a relatively ecumenical society. As early as the fifth century BC, Servius Tullius, the sixth king of Rome, distinguished civil crimes from criminal offences. Under this new, more enlightened approach to justice, capital punishment and the horrible pain that so often accompanied it, were reserved for offences such as murder, treason, arson, perjury and temple virgins who engaged in sex. In some cases, such as arson, the punishment remained ‘an eye for an eye’ – arsonists being burnt to death. Perjurers were thrown from a cliff and non-virgin virgins were buried alive. Even serious civil crimes, such as physical assault or robbery, were usually punishable only by heavy fines, although theft of a farmer’s crops was occasionally punishable by hanging. Exempt from all forms of torture were priests, children under fourteen years of age and pregnant women. Throughout this period – that is to say, during the days of the Roman Republic – justice was relatively even-handed and free citizens of Rome had no more fear of random acts of judicial violence than most of us do today. All that changed around 50 BC.

Julius Caesar was no saint, but as he only held power for about six months, he had little opportunity to change things for better or worse. What he did do, however, was pave the way for a string of emperors who were, to say the very least, less than pleasant people. Immediately after Caesar’s assassination, power fell into the hands of three men: Mark Anthony, Octavius Caesar and Marcus Lepidus. Partly due to the fact that this was a time of civil war, and partly due to their natures, none of these men trusted anyone, including each other. For the first time in Roman history it became a crime to speak out against the government. When the philosopher Cicero denounced Mark Anthony, he was summarily arrested, tried and executed. Not a good start for the new Roman Empire and things swiftly went from bad to worse. As with almost all dictatorships, the Roman Empire was governed by men who doubted their ability to retain power and feared anyone and everyone who might conceivably snatch that power away from them. The only way for such men to maintain power is to establish a climate of terror: all plots, both real and imagined, must be uncovered and examples must be made of any suspected conspirators. And as we discussed in the first chapter, it is precisely within this paranoid climate of fear and suspicion that tortures proliferate.

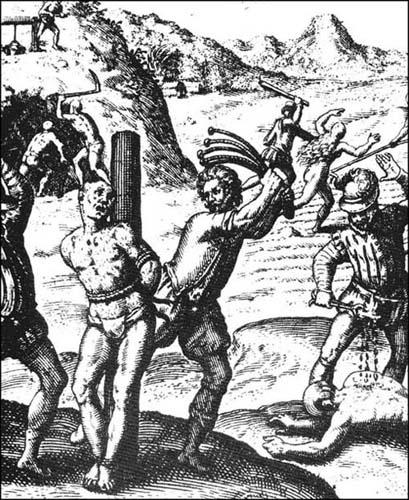

In this scene we are shown a man who is being flogged by two other men using what appear to be knotted ropes or perhaps chains with weights. To their right a victim is having molten lead dripped onto the skin of his back while in the background we see a man being lowered into a hole for some unknown reason and another man is on fire and being beaten with a club.

The first group to come under the harsh boot of Imperial tyranny was the Roman army. Not surprising, really, it was Julius Caesar’s legions which had overthrown the old Republic and it simply would not do to have soldiers thinking they could change the government at will. Under the Empire it became a dictum that a legionnaire should fear his officers more than the enemy.

In Roman military life, as well as civilian life, the most common punishment was whipping. Whipping was certainly nothing new; the Romans adapted it, like so much else, from the Greeks, but in the process managed to raise the humble whip to a torture device of impressive versatility. For mild offences they used a simple, flat strap – painful, but not life threatening by any means. The next step up was a whip made from plaited strips of parchment designed to flay the flesh from a victim’s back. Then there was a multi-thonged whip, the

plumbatae

, with small lead balls on the ends of the thongs, and also a version of the cat-o-nine tails, known as the

ungulae

, that had either thorns or bits of sharp metal braided into the thongs; in a few strokes it could slice to the bone. Finally there was a bullwhip-like beast specifically intended to kill. Amazing how much can be done with a few pieces of leather and a little ingenuity.

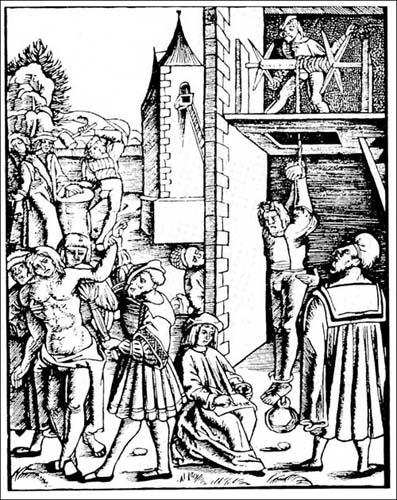

On the right-hand side of this woodcut, we can see the application of the torture of the pulley (also known as Squassation) the weights attached to his ankles serving to further dislocate his shoulders. On the left side of the image, another man is having his armpits burned with a torch (despite the fact that the rendering appears somewhat more like a feather duster). And in the background a criminal is having his hand chopped off or broken. Note the clerk judiciously taking note of any utterance made by the victim on the pulley while the torturer asks demanding questions.

The Romans were, if nothing else, an inventive people. Their engineers were the envy of the ancient world and many of the devices the engineer corps used to build roads and mount military sieges were equally adaptable to torture. Among these was the humble pulley. With pulleys, a man could be hoisted high into the air before being dropped suddenly to the ground. If he was particularly bad, he could be dropped onto a pile of sharp rocks again, and again, and again, until his flesh was ripped to shreds and his bones shattered. Alternatively, pulleys could be used to make an improvised rack on which a man’s limbs could be pulled from the sockets. Four simple pulleys, four small winches and some rope attached to a person’s limbs and a suspect could be torn limb from limb in a matter of minutes. All these devices, and more, were used by the Romans – not as a form of execution, but as a means to extract information from ‘suspects’ and even from potential witnesses. Under a string of increasingly paranoid Caesars, torture (and the state of fear that accompanies it) became a routine way of maintaining order in the empire. As devices once used for execution became tools for extracting information, new and more creative methods of execution had to be invented. Again, as they had always done, the Romans adapted, and improved upon, pre-existing techniques.

One of the more nefarious devices adapted by the Romans was the wheel, mentioned earlier. Unlike the Greek wheel, the Roman version was more like a drum than a cart wheel. In the simplest version, the victim was simply strapped to the outer face, or rim, of the wheel and rolled downhill until they were crushed to death. An alternative version had the wheel mounted on an axle and suspended over a fire pit, allowing the condemned to be cranked around, again and again, slowly being burnt to death – not much different than being spit-roasted, but a lot slower. For a more direct approach, there was yet another version of the wheel where the outer surface of the rim was set with spikes and it was across these that the victim was tied. On the ground beneath the wheel was another bed of spikes. When the wheel was turned the poor wretch was literally ground to pieces.

Possibly unique to the Romans was the sentence imposed on those who murdered their father. Patricides were tossed into a large canvas sack. Before the bag was sewn shut a handful of poisonous snakes were tossed in and the entire package was then thrown into a convenient river, lake or the Mediterranean.

All these creative tortures not withstanding, the method of execution most identified with the Romans will always be crucifixion. As early as the late Republic, crucifixion was adopted as a means of executing slaves convicted of capital offences, but it was not until the Empire that people other than slaves could be condemned to this particularly nasty fate. Because crucifixion was such a slow, painful death, and because it made such a grand public spectacle (particularly when large groups of victims were crucified together), it became a favourite method of disposing of ‘enemies of the state’. It was crucifixion that would eventually become the execution of choice for disposing of both the recalcitrant Jewish population in Palestine and the proliferating number of bothersome Christians who began infesting the Empire during the second and third centuries after Jesus.

At the time of Jesus’s crucifixion, around 27 or 28 AD, wholesale terror in the provinces was still in its infancy; Emperor Tiberius was too busy wreaking havoc back home. A half century later, when the Jews rose against Rome, Emperor Vespasian had plenty of time on his hands to crush the life out of them. When General Titus besieged Jerusalem in 70 AD, he crucified Jews at the rate of 500 a day. The problem was never finding enough Jews to murder, but finding enough wood in that arid land to build all those crosses.

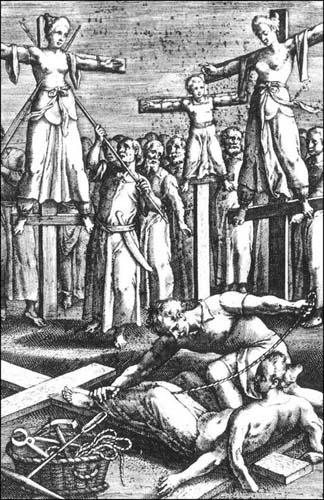

Here we witness the execution of four women by crucifixion. Note that the women are merely tied to the crosses and left to die of hunger, thirst and exposure. The woman on the left has been pieced through by lances and as such will die fairly quickly. It is uncertain whether the other three women will be granted a similar ‘mercy’.

Tiberius, mentioned above, reigned from 14–37 AD and was a paranoid misanthrope who hated his subjects nearly as much as they hated him. Never being a hands-on kind of ruler, he spent much of his later years isolated on the Isle of Capri and left the brutalising of Roman citizens to his henchmen. To wile away his idle hours, Tiberius had a constant string of prisoners brought to his island where he enjoyed thinking up particularly inventive ways of murdering them. Most of these victims were his political enemies, or at least he thought they were, and they were seized and hauled to Capri without either a trial or an arrest warrant. They simply disappeared. It was an amazingly subtle method of terrorising his opponents and one that would be used again and again over later centuries – specifically by dictators in Africa, South America and by one particularly vicious German despot. As was true under dictators in all time periods, there were a few who spoke out against the Roman use of torture. One of these was the philosopher Seneca (4 BC–65 AD), who recognised that torture was not only unjust but a terribly flawed way to discover the truth. Fortunately, Seneca never pointed a finger directly at the emperor and was never invited to spend a weekend on Capri: his message, if it ever reached Tiberius’ ears, went unheeded. As a last insult to the Roman people, Tiberius selected his insane nephew to succeed him – his name was Caius Caesar. We know him better as Caligula.

Like his uncle, Caligula preferred torturing people in private (such as in the same room where he was throwing dinner parties) over imposing terror on the population as a whole. Indeed, Caligula knew how to curry favour with the people of Rome and it was he who changed the Roman Games from true athletic competitions into the orgies of blood and death for which they are remembered. Fortunately, Caligula only ruled for four years before being murdered at the age of twenty-nine. Although his successor, Claudius, strove to return Rome to some semblance of sanity, his efforts were doomed. When his wife poisoned him in 54 AD, after a reign of thirteen years, she installed as emperor her son by a previous marriage – Nero.