The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History (4 page)

Read The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History Online

Authors: Daniel Diehl

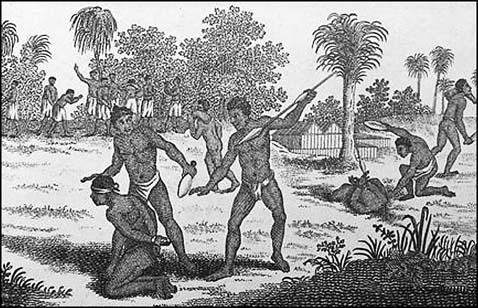

Here we see a public flogging taking place. This would have been a fairly commonplace scene throughout Europe until well into the eighteenth century. The victim here (apparently a woman) is being flogged with bundles of sticks (although being hung by the wrists is certainly unpleasant enough). It could well be that the man flogging her is in fact her husband and that he was legally entitled to this recourse for her shrewish behaviour or infidelity, but only if the flogging was administered publicly.

Hand-in-hand with the concept of whippings and other minor, public punishments was the concept of shame and humiliation which inevitably accompanied the punishment. The whole concept of shame has virtually disappeared from modern society, due largely to the anonymity of overpopulated cities and the breakdown of community and family life. Things were different in the past. Small communities, where everyone knows everyone else and knows all about their business, are a perfect platform for imposing soul-crushing levels of shame. In the tiny, isolated communities that existed from the dawn of civilization through the late eighteenth century, when friends, neighbours and family refuse to talk to, or do business with, someone who had stepped beyond the bounds of acceptable behaviour, it was a truly shattering experience. Add to this the fact that the offender had been whipped, or otherwise punished, in full view of the entire community and they would have probably been more than happy to exchange the experience for a few months in a nice gloomy prison where they could suffer in private.

As was true with minor crimes, the punishment for more serious offences was determined largely by how civilised, or how barbaric, the individual society happened to be. The time period in which the society existed had surprisingly little to do with how ‘civilised’ the punishments were. As we shall discover in the next section of this book, ancient Egypt was fairly civilised but 4,000 or 5,000 years later the punishments imposed during the Dark Ages and early medieval period were unbelievably horrific. Branding, dismemberment, scalping, ripping tongues out by their roots, throwing people from cliffs, skinning them alive and ripping their entrails from their still-living bodies were all commonly imposed punishments used in early European societies. So why did society seemingly deteriorate? In reality, it did not deteriorate at all. As we saw earlier, stable societies are less likely to fall victim to the paranoia that creates brutal punishments than are unstable societies. The Egyptians had a stable, well-organised society ruled by an ancient system of royalty and priests who were not in constant fear of being toppled. The societies of the dark and early Middle Ages, on the other hand, were tremendously unstable and tended to be led by whichever warrior had the biggest sword at the time. To such fearful leaders every lawbreaker offered a perfect opportunity to set an unmistakable example. As late as the Renaissance, punishment throughout Europe was at least as brutal as it had been under the yoke of the Roman Empire 1,500 years earlier. A single example should serve to illustrate this point.

These ankle restraints are from the eighteenth or nineteenth century when somewhat more humanitarian concerns affected attitudes towards imprisonment or incarceration. These have obviously been designed for prolonged use as they have been shaped to make them more comfortable and less irritating, and yet maintain restraint.

During the late tenth century, a bell maker from Winchester, England, named Teothic was arrested and convicted of what the church records (where the case is recorded) only refer to as ‘a slight offence’. Under the rules of Anglo-Saxon England – which was one of the more stable societies in northern Europe at the time – the wretched Teothic was shackled and hung up by his hands and feet. The following morning he was taken down long enough to be whipped unmercifully before again being hung up like a side of beef. How long this horrific punishment might have continued we do not know because somehow Teothic escaped captivity and took sanctuary at a local monastery.

When the crime is more serious than the one poor Teothic was convicted of – serious enough to demand the death of the prisoner, and bear in mind that as late as the eighteenth century, stealing a loaf of bread was a capital offence – the most unspeakable tortures can be justified under the concept that once a person has committed a serious crime they surrender every protection and comfort society extends to its law-abiding citizens. Once publicly placed outside the parameters of society, the malefactor could be legally dealt with – either swiftly and cleanly or in the most unspeakable manner imaginable. If his end was to come swiftly – relatively speaking – the most popular form of execution has always been by hanging.

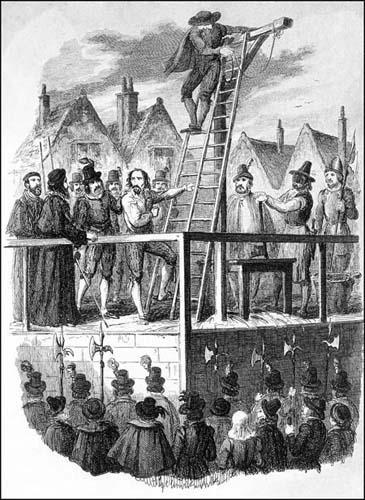

This engraving of a public hanging serves to illustrate what public spectacles these executions grew to be. Though we might assume by the presence of the masked executioner with the axe on the right, that this was not going to be a simple death by strangulation, but was, more likely, to have been a case of hanging, drawing and quartering as described later in this book.

Despite the fact that until well into the nineteenth century – when a trapdoor was installed in the scaffold allowing the condemned to be ‘dropped’ to a nearly instantaneous death – hangings were carried out by placing a noose around the prisoner’s neck and hoisting him into the air where he dangled, kicked and choked himself to death over the next ten to twenty minutes, hanging has never been considered torture. So if hanging was cheap, easy, relatively quick and never considered a form of torture, why were so many strange, bloody and painful executions devised for so many different crimes? Before answering this question, it might be well to recount the more popular forms of execution – and the concomitant crimes – still in use as late as the sixteenth century. The following list comes from 1578 when it was compiled by the English chronicler, Ralph Hollinshed.

If a woman poisons her husband she is burned alive; if a servant kills his master he is to be executed for petty treason; he that poisons a man is to be boiled to death in water or [molten] lead, even if the party did not die from the attempted poisoning; in cases of murder all the accessories [before and after the fact] are to suffer the pain of death. Trespass is punished by the cutting [off] of one or both ears … Sheep thieves are to have both hands cut off. Heretics are burned alive [at the stake].

Not included on this list are simple hangings; beheading in cases where noblemen were convicted of treason and hanging, drawing and quartering imposed on commoners found guilty of the same offence. Burning at the stake – that ever-popular horror – took several forms. When the person in question had been convicted of heresy, if they recanted their sin they were usually strangled to death, or hanged, before being consigned to the flames. If they clung to their heretical belief they were condemned to be slowly roasted alive. Simple cases of murder would lead a man to the gallows but a woman was more likely to be burnt. Why? Because the corpse was routinely stripped naked and left to twist in the wind after the execution and it was considered disgraceful to expose a woman’s bare body to the curious stares of the public.

In this illustration by Francisco Goya we see an execution by garrotte. This method rose to popularity in Spain during the years of the Inquisition and continued in use as late as the eighteenth century. The condemned is sat in a chair with a strap about his neck. The executioner slowly tightens the strap by way of a mechanism on the back of the ‘chair’ and slowly strangles the condemned to death. In some versions we find the presence of a spike at the back of the neck designed to pierce and sever the cervical vertebra thereby paralyzing the victim through the process.

Before we condemn all the long-lost kings, princes, judges and church-men who imposed such horrific tortures as barbarians, it is well to remember that, unless a nation had been overrun by a foreign power, governments generally keep their hold on power by pandering to the needs, beliefs and tastes of their people. Torture, at least when carried out in public, and public executions were not only accepted by the general populace but demanded by them. Any king who denied his subjects the thrill of an occasional flogging or hanging, risked being toppled from his throne by one of his fellow noblemen who knew how to keep the masses happy.

So far we have only considered torture as a means of punishment, or coercion, judicially inflicted by governments on their more disobedient subjects or hapless victims. Before moving on to a more complete history of torture we should look at another aspect which sometimes creeps into the already horrific annals of torture; the overall mind-set of those involved in the process at whatever remove. That is to say, the preconceptions and expectations of the individual being tortured, the person or persons inflicting the torture and, finally, on the public, which so often gathered to enjoy the spectacle of another human being subjected to unimaginable torment.

Since humanity’s earliest realization that there are greater powers in the universe than our own little selves, humans have had the sneaking suspicion that the gods – and later even God, Himself – demanded sacrifices in the form of human suffering. At first it was a way to make the gods take away the thunder. Next it was a way to ensure that the crops grew, or the upcoming battle was won and last of all it just became a way to make the gods happy. In many primitive societies, this sacrificial suffering took the form of human sacrifice – the Aztecs ripped out the hearts of prisoners of war by the thousands. In more advanced societies the sacrificial pain became a more personal matter: ‘If I have committed a wrong, then I must be the one to pay for it’. This concept of accepting personal responsibility may have originated among the ancient Egyptians. Records show that Egyptian priests in the service of the goddess Isis flagellated themselves during specific festivals. Similarly painful self-punishments have been practiced by Hindu holy men who inflict a staggering array of painful experiences on themselves as a demonstration of their faith in their gods and control over their own bodies. It is not surprising then, to find that early Christians engaged in a variety of spiritually cleansing acts; all of which were designed to show the penitent’s remorse, their desire for forgiveness and submission to the power of God.