The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History (14 page)

Read The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History Online

Authors: Daniel Diehl

When one plan fails, another is always devised to take its place. In 1381, when both the Statute of Labourers and the sumptuary laws failed to keep the working classes in line, the English Parliament enacted a flat tax of 1

s

on everyone over the age of fifteen. Considering the draconian measures that had preceded it and the fact that this was the second such tax in less than a year, it is hardly surprising that the peasants of Kent and Essex Counties rose in revolt. Under the leadership of anex-soldier named Walter (Wat) Tyler and a defrocked priest named John Ball, they ravaged the countryside, overran Rochester Castle, stormed London, burned and murdered their way through town, sacked the Tower of London, killed the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Lord Treasurer and paraded their heads through the streets of the city. In an act of unparalleled bravery, the fourteen-year-old King Richard II met with Tyler and his mob in an attempt to arrange a truce. The boy-king promised that if the mob would go home, the tax would be rescinded, more latitude would be given to the peasants, serfdom would be abolished and no reprisals would take place. Tyler himself was killed when he made an attempt on the King’s life, but the mob of thousands quietly dispersed. Richard undoubtedly meant what he had said, but as a minor, his word was not yet law. The Privy Council forced him to renege on his agreement. Later, addressing the representatives of the peasants, Richard is recorded to have said: ‘serfs and peasants you are and serfs and peasants ye shall remain’. Hardly a statement likely to engender good behaviour among the masses.

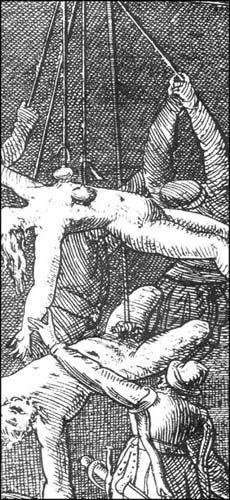

Detail of a Dutch engraving of about 1590, one in a series of fifty-three showing the massacre of the protestant citizens of Antwerp by the Spanish on 5 November 1576. Here we see three victims being tortured by suspension. The male is being suspended by his genitalia, the female by her breasts and the man in the background by his wrists. We do not think anything further needs to be said here to convey the agony of the victims which is not otherwise clear in the image.

As enlightened as he had been as a teenager, the harsh realities of politics and life in the Middle Ages eventually made King Richard as hard as his ministers. In 1383, an Irish monk gained an audience with the king and openly accused the Duke of Lancaster of treason. Whether or not Richard looked into the matter is unknown, but his reaction toward the monk’s effrontery was recorded by a court chronicler. ‘Lord Holland and Sir Henry Greene, Knight, came to this friar and, putting a cord about his neck, tied the other end about his privy members and after hanging him up from the ground [by this rope], laid a stone upon his belly, with the weight thereof … he was strangled and tormented, so his very backbone burst asunder herewith, besides the straining of his privy members; thus with three kinds of torments he ended his wretched life.’

By the end of Richard’s reign (1399) it was obvious that petty crime was completely out of control. To punish those who insisted on breaking the law, stocks were ordered to be constructed in nearly every town and village across England. As they had done in the past, the stocks provided both a means of non-damaging punishment and a satisfying form of public sport. Slightly less public, but equally effective, were the Jaggs; an iron collar attached to a length of chain fastened to the wall of the local church. Wrongdoers, particularly those who had broken church law, were locked in the Jaggs for a specified period of time so they might contemplate their sin in the shadow of God’s house. Similar iron collars and shackles were common in castle dungeons everywhere. In Carlisle Castle the iron collar was provided with such a short chain that if a prisoner happened to fall off the stone sleeping shelf they would almost inevitably strangle themselves. In some places such tragic accidents were avoided by fastening prisoners safely to the wall not only with an iron collar, but also with a waist band and shackles for the wrists and/or ankles – no chance then of tumbling out of bed and hurting yourself.

This device, once locked about a victim’s neck, would tether them to a wall, post or similar fixed object. Whether publicly (such as within a church or town square) or privately (such as within a prison or dungeon) it was a cruel and merciless form of restraint which would frequently be used in conjunction with additional tortures or torments.

In addition to stocks and chains there were specific forms of minor punishment devised for women. For common shrews and scolding housewives there was the ‘chucking stool’ – a chair to which these nagging women were tied before being processed through the town or village to the delight, taunts and hurled objects of passers-by. To make the humiliation as complete as possible, the chair had an open bottom and the woman’s skirts were hiked up before she was seated, leaving her rump exposed for the abuse and amusement of all and sundry.

For such mouthy women there was also a device known as the ‘scold’s bridle’, a nasty little cage of iron straps that could be locked over the condemned’s head. When the face plate was closed an iron tongue, fastened to the inner face of the bridle, was shoved into the woman’s mouth, preventing her from hurling curses at her tormentors and often causing severe lacerations to the tongue, cheeks and gums. Once locked firmly inside the bridle, the woman was then paraded through the streets of town.

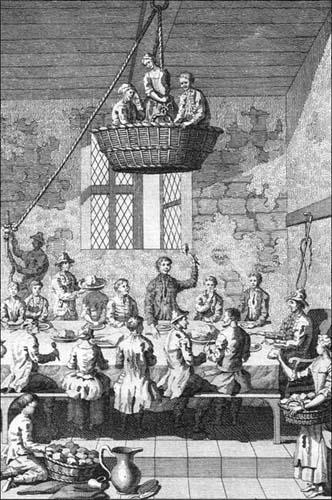

This image shows the punishment of women in a poorhouse found to be too lazy. It is similar to the punishment of the chucking stool in that the only real tortures endured by these women are a result of their isolation and exposure to public ridicule. In the case of a chucking stool, this might be in the public market square, whereas here it is in the communal dining hall of the workhouse.

For slightly more serious offences there was the ‘ducking stool’. Intended specifically for women of loose virtue and those for whom a turn on the aforementioned chucking stool had not proven a sufficient deterrent to their nagging ways, the ducking stool was suspended over the local pond and its occupant given a free swimming lesson. The amount of time she was likely to spend in the water was substantially increased if she were suspected of being a witch. If an accused witch floated, the assumption was that God’s good, clean water – used, as it was, in baptism – had rejected her evil person; if she sank, she had been accepted by the water and was therefore not a witch. She may have drowned by the time the determination was made, but at least she had died free of guilt. The pillory was also in constant use during the 1400s. Those found guilty of brawling, habitual drunkenness, rumour mongering (especially if it was against a public official or a noble family), slander and blatant infractions of fair-trade rules were all subject to having their head and hands locked into the pillory’s wooden frame and exposed to the contempt of the public for a period ranging from a few hours to several days. For those who continued to insist on the life of a vagrant when they were physically capable of holding down a job, the standard punishment was to be stripped naked, tied to the back end of a cart and hauled through the public streets while being whipped until the blood dripped to the ground.

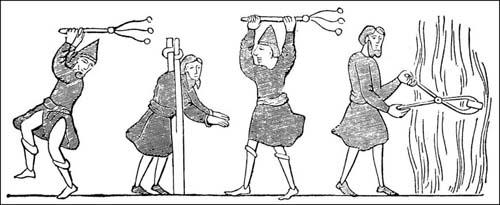

Saxon whipping and branding. From the Cotton MS. Claud B. iv.

Throughout the fifteenth century the most common form of punishment for capital crimes was hanging. This is not the form of hanging familiar to us from nineteenth-century photographs and cowboy movies, however. The condemned was not dropped through a trap-door where the sudden jerk would break their neck and end their life in a split second. All hangings, up until the mid-nineteenth century, were slow, painful, macabre affairs. Rather than being dropped through a trap, the convict was simply hauled into the air and left to dangle in the noose until they choked to death. In the case of the physically fit, or those with a heavily muscled neck, this could mean as much as twenty minutes of kicking and choking their life away. Unlike earlier periods, by the 1400s the right to hang someone found guilty of a capital crime was not limited to royal courts; every town and village worth its name had its own gallows and regularly dispatched those found guilty of murder, grand theft, desertion from the local militia, forgery, arson and any other crime which seemed to warrant it at the moment. Even when the gallows were kept busy it did not always satisfy the public demand for justice. In 1429 a woman accused of murder was seized and lynched by an entirely female mob – this was England’s first recorded case of an individual having been hanged without the benefit of at least some form of trial. Even in the face of such rude justice the social structure in England was about to break down even further.

For the three decades between 1455 and 1485 the English nobility went to war with itself. What has become known as the Wars of the Roses was actually a dynastic struggle between the noble houses of Lancaster and York for control of the throne. For a generation and a half the Lancastrians, the Yorkists and their hired armies of mercenary thugs slogged it out across the English countryside; the balance of power shifting one way and then the other until the nation, and the families involved, were nearly decimated. In August 1485, an army led by Henry Tudor – last surviving claimant to the Lancastrian line – met and defeated the forces of King Richard II at Bosworth Field. In claiming Richard’s crown, Henry Tudor (now Henry VII) inherited a kingdom where order existed only in theory. A few months after Henry’s ascension to the throne, the Venetian envoy to England wrote: ‘There is no country in the world where there are so many thieves and robbers as in England. Few venture to go alone in the country excepting in the middle of the day, and fewer still in the towns at night, and least of all in London’.

During the decades of turbulence the local courts had become corrupt beyond imagining, blithely condemning the innocent if there were a profit to be made in it, and for the same reason frequently turned dangerous criminals loose on society. Even where there was no corruption, there was massive incompetence. In an attempt to prevent wholesale injustice from consuming society, the Church routinely granted sanctuary to all who requested it and even those who did not seek sanctuary often escaped punishment by pleading ‘benefit of clergy’ – that is to say, ordained or not, the person in question claimed to be in the service of God. In a world where almost no-one except the clergy could read, the only proof required to qualify for benefit of clergy was to read the first verse of the fifty-first psalm: ‘Have mercy on me, O God, according to Thy loving kindness; According to the multitude of Thy tender mercies, blot out my transgressions’. How clever did a criminal have to be to memorise these few lines and simply pretend to read them when handed a Bible? The benefit of all this was that civil courts had virtually no control over clerics and clerical courts had no power to execute and seldom even imprisoned. Contrition and penance were considered the only earthly punishments needed by those in the Church – any additional punishment would be dealt with by God, in the hereafter. It may have been sufficient for legitimate clergymen and it may have provided a grand loophole for criminals, but it was not at all good enough for Henry VII and his Chief Justice, who is quoted as having said: ‘The devil alone knoweth the thought of man’.