The Big Music (60 page)

Authors: Kirsty Gunn

BBC: And you would have seen a lot of things back then you wouldn’t see now.

RG: Oh, yes, because folk would invite you in, you see. When you were only delivering once a week, it was a big occasion, the post coming like that. And there was this one house, ‘The Grey House’ it was called, and it was way up, oh up Rogart way, but miles and miles down a dirt road, a private road, you know, and oh the place was remote … And the post they had! This was the Sutherlands – and they had the Piping School up there, you know, everyone knew about the School, and they took a lot of post, international post. I’d arrive there – oh, with a bagful of letters and parcels – for it would be music, you know and reeds … And people would be sending him pipes for to have a look at, and this from all over the world … People sending him things from all over the world. So I’d go in there, I’d see Mrs Sutherland and she’d give me a cup of

tea, and Margaret would, for she helped out around the place, with helping to run the School and all the concerts they had and so on … And, oh, I was like Father Christmas with all the things I had for them in my bag, and this was maybe once a week, once a fortnight. It was a lovely house, a lovely atmosphere, if you like. A family, you see – and you’d go in with the post and you’d be part of things. There was a wee girl there, she was the daughter of the housekeeper, Margaret, and I’ve things for her also, you see, for she was doing some of her lessons by distance – this was in the days before they had set up proper transport and so on and the little ones in these remote places did some of their lessons at home … And I remember this one time she was running around the place shouting ‘I’m not going to school! I’m not going!’ and I arrived, you see, with some book or other for her to study, and her mother said to her, ‘Well, the school has just arrived for you!’ – for that was my role, in a way, to bring everything in …

Further material available:

Sections of various letters – including courtship of Callum and Elizabeth – also samples of scanned ‘originals’ of some letters dating back to Victorian times. Also accounts of clothing, personal items bought, stationery, books etc.

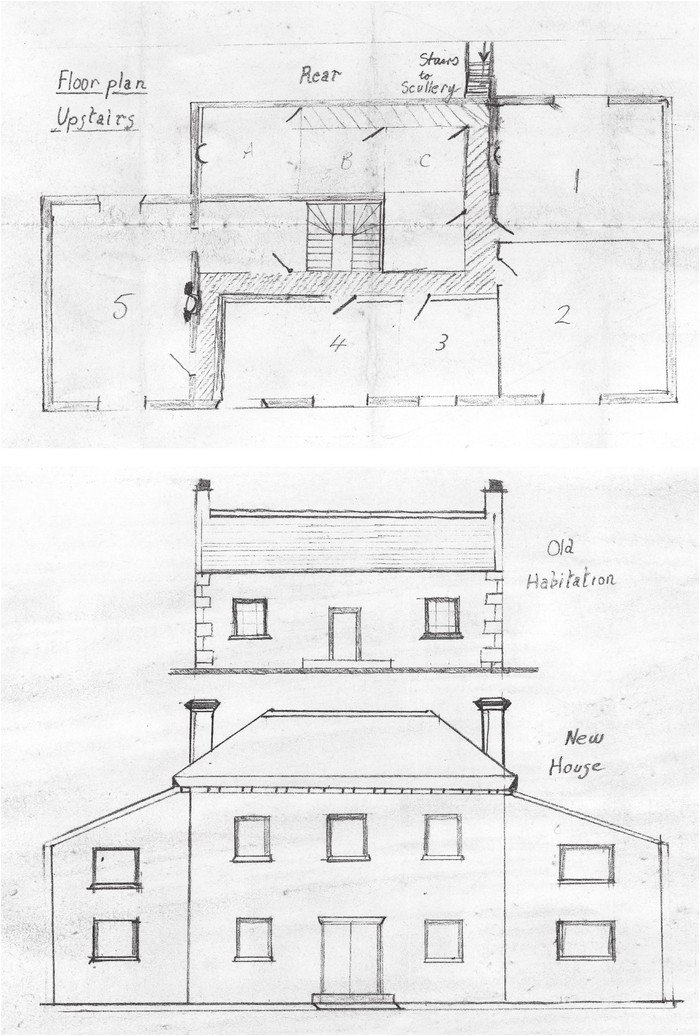

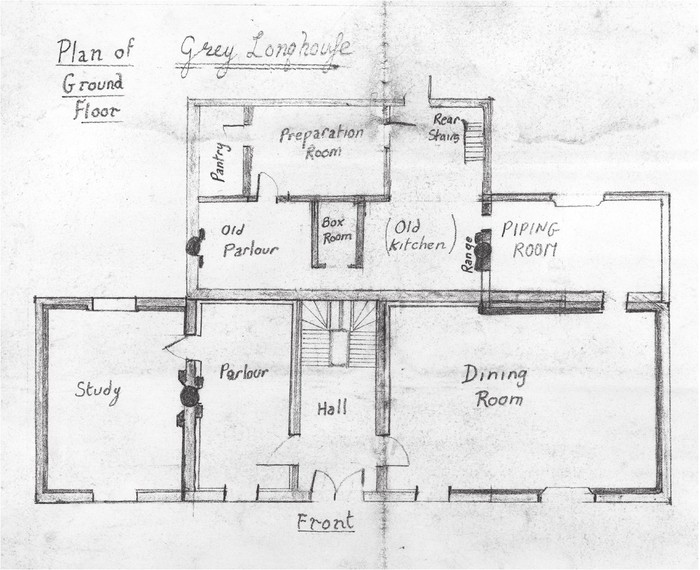

Many records of domestic life at The Grey House – some dating from as early as the mid-eighteenth century – are available for perusal at the University of Dundee archive. These records include recipe books and notes, a Visitors’ Book that keeps a file of all house guests – including those who attended various Schools and recitals, programmes of recitals – house plans showing additions and improvements etc.

An example of the above is shown below:

fig./five – plans of the house showing extensions and additions.

The following are available in archive:

Land acquisition papers and legal documents

Pages from recipe books and related notes

Pages from Visitors’ Book; also list of all piping pupils and some recital

programmes

; also examples from Elizabeth Sutherland’s journal ‘Recollections of The Grey House’

Home improvements and decorating papers – including wallpaper and fabric swatches

Garden journals and related letters

Linens inventory

Books and examples of work and drawing from the Schoolroom

fig./six – photograph showing Schoolroom at The Grey House

Additional musical information

‘Innovations to the Piobaireachd’

by John Callum MacKay Sutherland, The Grey House, 1997

(from an address given to the Piobaireachd Society by J. C. M. Sutherland, July 1974)

To those of you unfamiliar with some of the developments taking place in the playing and composition of certain Ceol Mor tunes, I have been asked to give a brief description. These developments are by no means sudden or unexpected. Those of you who were familiar with my own father’s style of playing will know him to be a player always alert to the various possibilities of execution within a composition. Indeed there are those who would say that my father never played the same tune twice – that there was, to quote his own word for it, a certain ‘heuristic’ approach to his playing that meant he could only ‘find the tune’, again to use his own expression, by ‘playing into it’, thereby allowing certain notes and phrases to find their own individual expression.

It is with this approach in mind that I have gone to my own pipes – viewing them and the traditional tunes also as a ‘means to an end’, that is, as a base from which one’s own musical interpretation may grow and flourish.

Now there will be many among us, purists and traditionalists both, who will be against this method of play, first set down formally, in papers given, and so on, in books and lectures, by my father and now taken up, one may say, by the son! Yet I would say to those men that there is nothing so wayward about this approach – when we consider the historical tuition methods of the bagpipe that were always conducted via canntaireachd, a musical method that is in itself somewhat modernist, ‘heuristic’, if you like, in origin. For when a tune is sung to a pupil, the day it is sung, the mind and the mood of the singer, whether it is hot or cold … All these details and circumstances will come to colour the tune in particular subtle and sometimes dramatic ways. So it is impossible for a piece of music to be sung in exactly the same way twice – no matter how the traditionalists may long for such order in life! – in the same way might it be with our playing of that same tune.

It was this kind of thinking, then, that led to me developing my own composition work in certain ways that might allow for the ‘mood’ or ‘change’ in a tune to be more apparent – which is why, as many of you in this room will know, I have gone to some of the great German classical music composers for instruction, to learn from them, how emotion and a certain ‘story’, if you like, that we might allow the tune to sing, may come to dominate the overall texture of a piece, rather than its notes and structure.

This is not to say, of course, that some of our greatest traditional tunes do not have such a story to them, such emotional force. We all know the power of the Ceol Mor compositions and it would be presumptuous of me in the extreme to suggest I am doing something new here. No, it is my aim simply to bring to the fore certain practices employed in my own work – the use of leitmotif, in particular, that repetition of certain phrases or musical ideas throughout a piece that work to build up an emotional landscape in a piece as first defined by Wagner, or the use of suggestion as first introduced by Beethoven, where a theme may be hinted at but not fully allowed in to the tune until later, creating a present and past in a piece, and so on – to bring these forward for your attention as ways of extending the reach and depth of my own compositions, to give them some power and force that the arrangement of a theme with its Taorluath and Crunluath would not otherwise allow me.

Call me musically bereft, if you like, that I have not the great imagination of a MacCrimmon that I need to rely on such devices! You would be right – my own scattering of notes across the page would not suffice. But add to that scattering some repeat, some simple recall of a past theme, or the merest change of an embellishment to bring about a shift in atmosphere … Then I have a piece I can be pleased with, that might give me pleasure to play, that, as we hope with all musical endeavour, might bring pleasure to others.

In conclusion, therefore, my argument would be that there is room for both approaches in our play, that our repertoire is solid enough, is established and formal enough, to allow for the arriviste! Permit me, then, to play for you now one such new arrival – a tune I have been at work on over this past year. I have entitled it ‘As the Deer Come Down from the Hill’.

Taken from a report, by Jack Taylor of The Piobaireachd Society, of a recent conference:

We were gifted with a number of speakers all attending to the theme: ‘Piobaireachd and the Imagination: Applied and Research-based Approaches’ and there could be no doubt that it was a subject with rich implications for the scholar and musician alike. The overall ethos of the conference was one of imaginative and scholarly

investigation

of a musical form that remains as complex and rich to us after many years of study as the day when we first arrived at it, chanters in hand, music in our heads.

Now for the details …

Keith Sanger tends to spend his time in the National Library of Scotland – and there he found papers telling of the pipers of the Breadalbane Fencibles, with particular emphasis on John MacGregor. The Fencibles began recruiting in 1793 – and John wasn’t too keen to join, as he didn’t have a bagpipe. Perhaps the incentive to him of having the regimental pipes to play, together with the promise of adding land to the family smallholding, was enough to persuade him. In any event he soon had his own pipes, as he won the prize pipe at the Highland Society competition that year. The regiment had a poet, too, and pipers won’t be pleased to know that he was paid fifty per cent more than the pipers.

Jim Barrie’s presentation entitled ‘Select Features of the Cameron Style’ had received the accolade of a prior editorial in

The Piping Times

hinting ‘what is all the fuss about?’ Jim started by saying that his father often said that the old pipers in Scotland all played in almost the same way, except for preferential differences, and finished

with a quotation by Duke Ellington – ‘If it sounds good, it is good.’ In between, in the Piobaireachd Society’s first PowerPoint presentation, he skilfully showed, with musical examples from Robert Reid, Andrew MacNeill, Willie Connell, Willie

Barrie

, Jim Barrie and Robert Brown, just what the differences, however small, are. What is not in doubt is that these nuances can significantly alter the musical impact of a tune. Jim showed this very well in the evening with his fine playing of ‘Marion’s Wailing’.

US piper Derek Midgely and Crieff man Craig Sutherland put their playing forward for dissection by Andrew Wright in a repeat of last year’s successful

masterclass

. Andrew showed how they might improve their performances – a plate of soup came into it somewhere – and he indicated how much difference little changes can make to musical effect. Derek left with some new ideas about how he might present ‘Lament for Patrick Og’ and Craig was given pointers about balancing the phrases in the rarely heard ‘Lord MacDonald’s Lament’.

After dinner Society ex-treasurer Donald Martin had gathered eleven volunteers to play. Instructed by Donald to lead from the front, Jack Taylor started it going with the ‘Vaunting’, including a presidential tuning pause. We then heard ‘Sir James MacDonald of the Isles’ (Walter Gray), ‘Battle of Auldearn’ (Rae Bell), ‘Too Long in this Condition’ (John Shone), ‘Corrienessan’s Salute’ (Bill Witherspoon), ‘Mac-Dougall’s Gathering’ (Peter MacAllister), ‘Marion’s Wailing’ (Jim Barrie), ‘MacKay’s Banner’ (Alan Forbes), ‘A Glase’ (Rory Sinclair), ‘Hiharin Odin Hiharin Dro’ (John Frater), ‘Macrimmon’s Sweetheart’ (Alistair McQueen).