The Big Music (53 page)

Authors: Kirsty Gunn

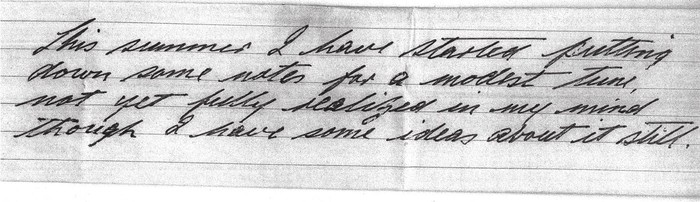

The excerpt from John Sutherland’s notes as mentioned above:

Note: To hear how this ‘modest tune’ may have been developed into the full piobaireachd ‘Lament for Himself’, it is possible to download the finished composition, which was completed for the project of this book by an anonymous piper and composer, from a website that is being created for ‘The Big Music’.

10

B

: The piobaireachd ‘Lament for Himself’ and the Little Hut

As is described in the Urlar and following movements of ‘The Big Music’, most of John MacKay’s creative thinking and planning took place not in the Music Room of The Grey House, as was traditional, but in a little bothy or hut he had built himself, secretly, in the hills between Mhorvaig and Luath.

This place, ‘the Little Hut’ as it is called throughout ‘The Big Music’ or ‘TLH’ as John Sutherland himself refers to it in his notes, became more and more a refuge for him as the years went on, a place of great privacy where it seemed the choices he had made for himself in his life – to do with being isolated and not allowing himself to be open or free with anyone, even the woman with whom he was most intimate throughout his life and who he might have allowed himself to love – played out as thoughts, ideas for music and themes in the remote and basic little hut in the hills, with its divan, its window, its desk.

The Crunluath A Mach section of ‘The Big Music’ contains material that was taken from the Little Hut and used for the completion of this book. It indicates

certain notes, fragments of manuscript with markings and small journal extracts that may help the general reader come to know more about how the piobaireachd ‘Lament for Himself’ came about; how sections of it were created in manuscript or as notes for composition well before John Sutherland came to write down his Urlar in full or ‘The Big Music’ itself was gathered into a unifying whole. Hence, we see certain themes and ideas shown in small remarks and sections of music that may not have added up to a clear musical idea to the composer at the time, but that have a certain meaning within this book.

The idea of a secret, of great privacy being at the heart of the creative act, is of course an idea as old as poetry and time. That Helen and Callum found the Little Hut when they were no more than children and went there, that the same private place contains the scattered beginnings of every aspect of the entire story of ‘The Big Music’; that everything Helen needed to start gathering her papers was already there … All this is as inevitable a conclusion to the elegy you have been reading as the hills themselves.

The following excerpt, appearing as scattered notes and taken from one of the

journals

found up at the Little Hut, may be of interest:

There must be a sense of ‘carpe diem’ about the whole – a snatching of life out of death’s grip – but how? That snatching away? A sudden drop of notes to do it? Plan for this …; Callum also must have a note, a small series perhaps, in the mid range, and quiet, so you might not notice the notes as a pattern at first … The quietest of doublings. The A Mach will be difficult – all pride, pride leading up to it … But somehow … Different. A different interpretation. As though the composition might be finished in another’s hand, as though – … A different set of notes but they are the same.

And:

Callum’s theme will only announce itself in the variations – I can’t hear it in the Urlar at all. But the theme will come in all the same. It will be there in the Taorluath, from the outset, and quite clear – a branching off from the Urlar that way, you could say, in a way that seems new – but no. For the notes have already been sounded. In the repetition. That’s the way to do it. So his theme might match the ambition of the repetition, yes. What I’ll call the ‘breathing’ notes, that sound as a sequence in the first four bars … That repeat might also contain … My father. And my son.

More notes of this sort can be seen in the Crunluath A Mach movement, and are detailed in the List of Additional Materials section of ‘The Big Music’.

The following information is sourced from

Piobaireachd: Classical Music of the Highland Bagpipe

by Seumus MacNeill, acknowledged to be in the tradition of such writers about piobaireachd as Major General Thomason, the compiler of

Ceol Mor

in 1900, and, in the last century, the work of Mr Archibald Campbell of Kilberry. Mr

Seumus

MacNeill held the position of Joint Principal of the College of Piping between the years 1959 and 1974, and delivered a series of lectures in 1968 that are still talked about to this day and were most useful when gathering information for these

Appendices

. More details of this publication are available in the Bibliography, as are other related materials that may be of use for those wishing to further their

understanding

of this music’s structure and content.

Like the concerto, with which it is compared, the form of the piobaireachd can be best described as a theme with variations. This is the one steady truth that can be set against it – while all other claims made about the music must be qualified and considered.

It is made up of three or more ‘movements’ – the Urlar, or ground, which is the laying out of the basic musical idea that will dominate the piece; the Taorluath (often attached to the Leumluath in meaning), which is a great development of that theme, a sort of branching out or leap (Leumluath translates, from the Gaelic, as ‘Stag’s Leap’); the Crunluath, or ‘crown’, which is an extravagant play of variations and embellishments upon the theme; followed by the Crunluath A Mach, in which the piper himself is describing his own virtuosity in his play – an embellishment upon embellishment, if you like, of the intricacies of the Crunluath – a fully flexible and reflexive aspect of the music on display; closing finally with the opening lines of the Urlar played again as a mark of final humility and simplicity after all that has preceded.

Within each of these movements are variations and embellishments – described in ‘The Big Music’ as separate but connected details of the story, and in musical detail in Appendix 12: ‘The form of a piobaireachd’.

Composed especially for the music of the Highland bagpipe, it has been said of piobaireachd that the only other musical instrument that can come anywhere near its sound and quality is the human voice. This was most certainly a given in those years before 1803, before written notation was introduced, when all piobaireachd was passed down from the teacher to the pupil by singing the tune, note by note, in a method of transmission known as canntaireachd. This method today is still

of much value, as singing can bring out the expression of the music in a way staff notation can only hint at.

For this reason, perhaps, it has not been the historical practice to make any great effort to write piobaireachd correctly. After all, if it is generally believed that one can only learn to play the music from one who has been properly trained to play it, who knows by heart and by memory every note of every tune that he may sing it to himself and others as well as play it on his pipes … Why then would the printed manuscript come to have much value from the start? One would always, in the first instance, want to hear the tune – not read – but as it sounds. In addition, collections of piobaireachd music are only intended to be of interest to pipers, since the music cannot be played satisfactorily on any other instrument. As Archibald Campbell noted (see Bibliography/Music: Piobaireachd/primary:

The Kilberry Book of Ceol Mor

), writing of staff notation applied to piobaireachd: ‘It makes no pretense to be scientifically accurate, or even intelligible to the non-piper. Call it pipers’ jargon and the writer will not complain.’ Subsequent to his remarks, there have been perhaps a hundred tunes written without bar-lines, published as

Binneas A Boreraig

by Roderick Ross (see Bibliography), which shows how important it is that pipers are not restricted to the rigid bar-lines and time signatures of classical music when playing. It is, of course, a convenience in memorising a tune to have the phrases, or parts of the phrases, in bars, but when playing a tune, the best and most musical of pipers will bring out the phrasing and timing in their own ‘time’ – creating their own bar-breaks, so to speak, so as to best express the depths and mysteries of the music.

By tradition, all piobaireachd is played from memory – thus involving a

considerable

mental feat akin to the soloist of any classical instrument – considering especially that a tune may last for fifteen minutes or more, and is played without the prompts of an orchestra or conductor for that length of time. In order to push phrases into a suitable bar pattern, it has often been found necessary to write some notes as gracenotes and mark pauses wherever seems relevant. Occasionally a pause mark will land on a gracenote, and, as a gracenote is not supposed to have any duration anyway (it takes its time from the note following), this causes

considerable

confusion even among pipers.

It may well be, then, that the more incorrectly a piobaireachd is written, the

better

it is to be played – because the learner is forced to seek assistance from a piper who knows more than he does and who has been taught himself in the traditional manner.

The real reason, however, for not attempting to write piobaireachd accurately is that the effort to do so – when one gracenote alone can be worth entire bars of manuscript – would be tremendous, and even then the result would only be one man’s interpretation of how the piece should be played. In addition, no piper really

believes that the great music can be learned without personal assistance from an expert.

Piobaireachd, Ceol Mor or pibroch, as it is known in its Anglicised form, is a form of high art, a musical genre associated primarily with the Scottish Highlands that is characterised by extended compositions with a melodic theme and elaborate

formal

variations. It can only be performed on the great Highland bagpipe, with its distinctive tenor and bass drones that sound at a particular interval so as to underlie strangely and exhilaratingly the tune being played.

Traditionally, many pipers prefer the name Ceol Mor, which is Gaelic for the ‘Great’ or ‘Big’ music, to distinguish this complex extended art form from the more common kinds of popular Scottish music such as dances, reels, marches and

strathspeys

, which are called Ceol Beag or ‘Little Music’.

Here follows a general introduction to this form of music about which still relatively little is known – from its enunciation to structure to history and known sources of its tunes.

Etymology

The word piobaireachd is first found registered as written in Lowland Scots in 1719, derived from the Gaelic word ‘piobaireachd’, which literally means ‘piping’ or ‘act of piping’.

There is some disagreement surrounding the terminology. The spelling variant used by most dictionaries is pibroch but most who are involved with the music, including the Piobaireachd Society, prefer the Scottish Gaelic spelling. Nonetheless, the pronunciation of piobaireachd is usually rendered identically to pibroch (that is, with a long i and a soft k sound for the ch, so:

pee-broch

) and in modern

English-speaking

contexts both piobaireachd and pibroch are equated with Ceol Mor.

Notation

Piobaireachd is properly expressed by minute and often subtle variations in note duration and tempo. Traditionally, the music was taught using a system of unique chanted vocables referred to as canntaireachd, an effective method of denoting the various movements in piobaireachd music and assisting the learner in proper

expression

and memorisation of the tune. The predominant vocable system used today is the Nether Lorn canntaireachd sourced from the

Campbell Canntaireachd

manuscripts (1797 and 1814) and used in the subsequent Piobaireachd Society books. The

Bibliography

has further details of all these manuscripts and subsequent volumes.

Multiple written manuscripts of piobaireachd in staff notation have been

published

, including Angus MacKay’s book

A Collection of Ancient Piobaireachd

(1838), Archibald Campbell’s

The Kilberry Book of Ceol Mor

(1953), and the Piobaireachd

Society

Books, published in certain sequences from the turn of the twentieth century to the present day.

The staff notation in Angus MacKay’s book and subsequent Piobaireachd Society-sanctioned publications is characterised by a simplification and

standardisation

of the ornamental and rhythmic complexities of many piobaireachd

compositions

when compared with earlier unpublished manuscript sources. A number of the earliest manuscripts, such as the

Campbell Canntaireachd

manuscripts that pre-date the standard edited published collections, have been made available by the Piobaireachd Society as a comparative resource.