The Big Music (49 page)

Authors: Kirsty Gunn

To many landlords, however, ‘improvement’ and ‘clearance’ did not necessarily mean depopulation. And neither did it mean that all parts of Sutherland, nor all those who lived there, were adversely affected. Without taking up the position of the powerful hypocritical factors and commissioners who policed the Clearances through the region, some families and certain individuals managed to maintain the small landholding they had inherited and develop this, in line with the innovations that were sweeping Scotland, to grow and extend their interests without giving up their sense of moral obligation to their communities or compromising a way of life that had defined them as long as they had been living in the region. The Sutherland family of the Parish of Rogart is an example here (see relevant sections of ‘The Big Music’, in the Taorluath and Crunluath movements, in particular). These families managed to make good their place in the North East and, due to strategic thinking and forethought, remained unmoved by the eviction processes that were eliminating and ‘disappearing’ their neighbours. As the shockwaves from the Clearances subsided, by the end of the 1800s, these same families were revered in the region and cited as examples of all that was commendable in the Highland character – strong-willed, decent and undeterred by fortune and politics. As time went on, their position in the community became, if anything, more associated with an old way of life that was enacted as if the Clearances had never happened. It was as though the brutality of that regime had only served to establish the place of decency and honour and fairness that had always been the virtues of home.

Family records

There are many pieces of documentation that indicate how life was lived,

particularly

from the period 1850 onwards, that are available in ‘The Big Music’ archive. These include first-hand accounts, records of fishing; crofting rights, small

documents

of the Sutherland family; landholding, sheep sales etc., and notes of piping lessons, pupils. See sections in the List of Additional Materials: Archive of John MacKay Sutherland.

Story of a Highland estate

It is not always the case that landholdings in the North East have been maintained by powerful, aristocratic interests that are not sympathetic to the indigenous way of life. The Grey House and holdings of Ben Mhorvaig in Sutherland, as described in ‘The Big Music’, is one example of private and substantial landholding in the

Sutherland

region that sits outwith the larger estate-owned tracts of land and occupies an independent place within Highland geography.

See the accounts of the positions and buildings of certain tacksmen and tenant farmers outlined in

The Highland House Transformed

and other relevant histories listed in the Bibliography at the back of ‘The Big Music’ to gain an understanding of how a prosperous class of people grew out of the traditional landholding interests in the North East and other parts of the Highlands. The Statistical Report for the Parish of Achtattan, 1823, for example, contains this quote: ‘The farmers make a decent appearance, seem to enjoy the comforts and conveniences of life’; and case studies abound of small farmers who increased their holdings and social and economic position all over the Highlands by prudent management of stock and land and fair and inventive methods of land lease and rental. These methods are reflected in the kinds of houses built, their scale and detailing, though the following comment is worth noting in light of houses such as The Grey House of ‘The Big Music’ and a consideration of how certain class distinctions remained in place even as they were collapsed by ingenuity and private interests: ‘However, although finished to the highest craft standards, the largest farmhouse remains similar in form and ornament to the smallest farmhouse. Decorative features such as columned porticoes or pediments were associated with a higher social status than that of tenant farmer and their use would have been inappropriate irrespective of the farmer’s actual worth.’ (from Maudlin,

The Highland House Transformed,

p. 69).

See too the story below, taken from a local pamphlet ‘Melvich and Naver District’, of the Dundonald Estate in the North East Sutherland/Caithness borders, for an example of a landholding with a history and background not dissimilar to that which governed the interests of the Sutherland family of Rogart, subjects of ‘The Big Music’:

Today, Dundonald Estate and The Big House and cottages are two independent Highland Estates that have always stayed outside the clan system of landholding in the north east and are representative of extensive though modestly represented economic interests.

The ‘modern’ story of the estate begins with the participation of Donald MacKay MacDonald in the Jacobite Rising of 1715 and the resulting forfeiture

of land he held further south that brought to an end the essentially feudal landholding system practised in that region. At this point he retreated to the far north where he took up residence with the Donald family who had acted as foresters to the Earls of Farr from at least the 17th century – the duties of forester were to ‘protect the game, to supervise timber-extraction, to conserve the woodland, and to apprehend trespassers.’ During this time he secured the property known as ‘The Big House’ and its surrounding land and, as a result of resolving the forfeiture of 1716, was able to buy an adjoining property that later became known as The Dundonald Estate.

The next owners of the Estate were his sons, James and Duncan MacDonald, who increased the landholding to the north, including securing fishing rights extending from the Fastwater of Clear, to the sea. Papers give the year of this purchase as 1739 – however, some National Survey documents suggest 1745 is more likely – as we have surviving three letters from the then vendor Lord Naver detailing his difficulties in selling ‘such choice and favoured waters such as I would prefer to keep them for myself.’

Nevertheless other records make clear that Lord Naver’s intentions were to sell this portion of land so as to help ‘provide’ for James MacDonald’s wife and son – Frances, herself a cousin of his, and ‘the boy John who has always been my favourite’.

When, in subsequent years, the Estate fell on difficult times, at no point were the fishings sold for these sentimental reasons – and they remain in the possession of the MacDonald family to this day.

In general, then, we see how the Estate has been held and managed independently since the eighteenth century despite a landholding system that was, at the time of the redeployment, still essentially feudal – with the landowner himself and his sons and grandsons (John and Donald MacDonald, sons of John) continuing to act as foresters, and feuars in their own right. Along with him other feuars who managed land this way include John Farquaharson (Invercauld), Patrick Farquaharson (Inverey), Donald Farquaharson (Allanaquoich).

Dundonald remains in private ownership today, though much reduced. The Big House is rented to fishing parties, and some stalking is available on the Estate.

Literary history

Caithness and Sutherland gave birth to a strong lyric tradition that came to

prominence

around the time of the Jacobite Rebellion. A large body of these songs survive and are sung today, though not always in the original Gaelic.

Poets of this era include Rob Donn MacKay, Duncan Ban MacIntyre, William Ross and Alexander MacDonald, who was present when Prince Charles raised the Jacobite standard at Glenfinnan.

The Sutherland poet Rob Donn MacKay did not take part in the rising, and his chief – Lord Reay – supported the Hanoverian side (the incumbent rulers). But Rob was still for the Prince, as this fragment shows:

Today, today, tis right for us

To rise up in all eagerness,

The third day since the second month

Of winter now has come to end;

We’ll welcome thee full heartily,

With laughter, speech and melody,

And readily we’ll drink thy health,

With harp and song, and dancing too.

Prolific creators or rewriters of Jacobite songs based on old models included James Hogg, Lady Caroline Nairne and Robert Burns. Burns published ‘It Was A’ for Our Rightfu’ King’, ‘The Highland Widow’s Lament’ and a song about love called ‘Charlie He’s My Darling’. Lady Nairne wrote lyrics for ‘Wi a Hundred Pipers’ and ‘Will Ye No Come Back Again?’ She also wrote a more warlike set of words for ‘Charlie is My Darling’.

March tunes had lyrics attached, for example ‘The Sherramuir March’ and ‘Wha Wouldna Fecht for Charlie’. James Hogg wrote Jacobite lyrics for both of these tunes and many others. Hogg published and perhaps wrote ‘Both Sides of the Tweed’, a popular song known today.

Later, the work of Neil Gunn and George MacKay Brown, in particular, came to represent a way of life that is depicted in mythic, lyrical terms as well as the actual and historic. Gunn’s famous novel

The Silver Darlings

and his

Green Isle of the Great Deep

are two examples on different ends of the literal/literary spectrum, both describing, to different degrees, a place that is both real and unreal, factual as well as fictional. In this, he and Brown, both, reach back to a tradition outlined above and before it, of fairy tale and Norse myth, of song and story, where the literal and invented worlds merge and blend in our imagination, become the same place.

The unequal concentration of land ownership remained an emotional subject, of enormous importance to the vexed question of the Highland economy, and

eventually became a cornerstone of liberal radicalism. The crofters (tenant farmers who rented only a few acres) were politically powerless, and as a result of this, it has been suggested, many had joined the breakaway ‘Free Church’ by and after 1843. This evangelical movement was led by lay preachers who themselves came from the lower strata, and whose preaching was implicitly critical of the established order. The religious change energised the crofters and separated them from the landlords; it helped prepare them for their successful and violent challenge to the landlords in the 1880s through the Highland Land League. Violence erupted in different regions throughout the Highlands during this period, only quieting when the government stepped in, passing the Crofters’ Holdings (Scotland) Act of 1886 to reduce rents, guarantee fixity of tenure and break up large estates to provide crofts for the homeless. In 1885 three Independent Crofter candidates were elected to Parliament, which gave voice to grievances formerly silenced. The results included explicit security for the Scottish smallholders; the legal right to bequeath tenancies to descendants; and creating a Crofting Commission. The crofters as a political movement faded away by 1892, when the Liberal Party came to represent, more and more, the interests of the tenant farmers of the region. Yet, as we saw over the previous historical period, there remained certain families and interests outside the general political movement that was changing the way Highland society was being managed. Always, it is important to bear in mind the way the land, in the region of north-east Scotland, accommodated a range of economic and cultural ambitions that in turn gave much back to the community and society in terms of enlarging the sense of Highland life and expanding its horizons.

One particular section of Sutherland that has, since the middle of the nineteenth century, resisted the changes that were sweeping the rest of the Highlands is the land around the hills Mhorvaig and Luath, an area that has been settled, records show, since and before the mid-eighteenth century by the Sutherland family, first of ‘Grey Longhouse’, Parish of Rogart and environs. See the following Appendix 4: ‘The Grey House’ for more details of the family’s history and activities throughout this period, as well as certain sections in the Taorluath and Crunluath movements of ‘The Big Music’.

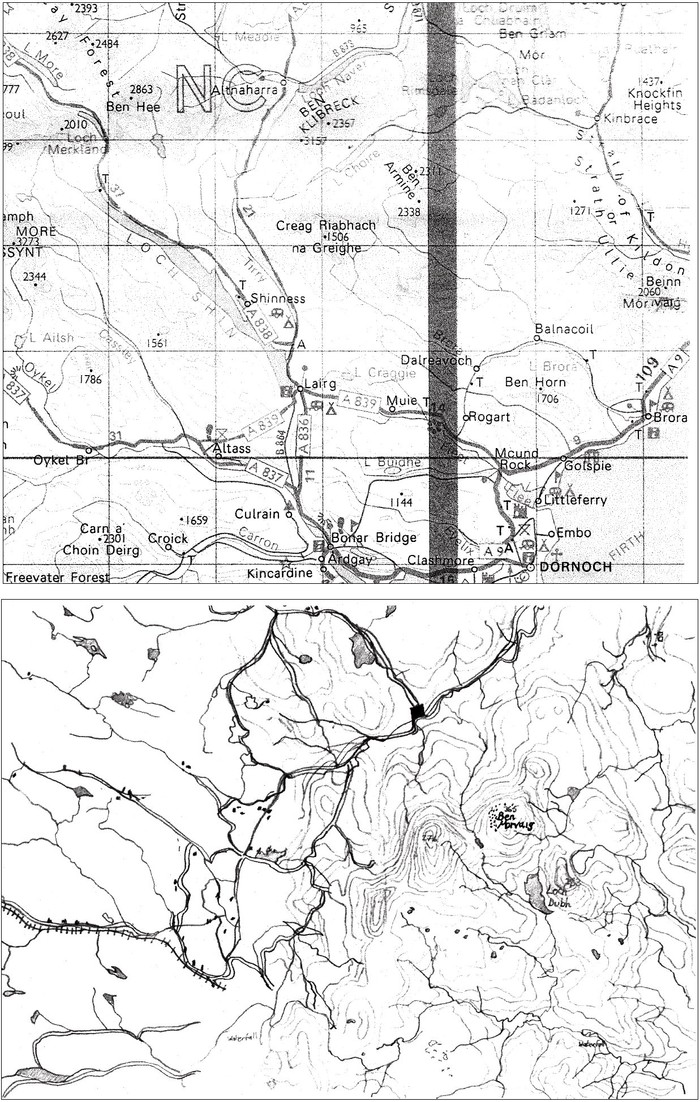

Local maps

Maps indicating immediate region; incl. rivers; landfall

i

Site

As described in the Taorluath section of this book, The Grey House – also known as ‘Ailte vhor Alech’ or ‘The End of the Road’ – was originally a traditional Sutherland ‘longhouse’ or ‘blackhouse’, the foundations of which can still be seen to the side of the current structure, comprising the kitchen and larders. This longhouse, of two rooms with a connecting space to link them, was built – probably over an existing dwelling – around the early eighteenth century and was established as a place of shelter for those passing through the ‘corridor’, as it was known in the time of the great sheep droves of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, that commences inland from the northwest of Brora and provides a route through the great hills of Mhorvaig and Luath all the way to the markets of Lairg on the west (see relevant maps in preceding Appendices).

The site is on an elevated position at the northern end of the strath known as Blackwater, run through as it is with one of the tributaries of the river bearing that same name, yet well sheltered by Ben Mhorvaig at its back and Ben Luath beside it. It is some two-thirds of a mile from the river Blackwater ‘Beag’ and is south-facing, well drained, on soil that comprises Torridonian sandstone with peat depositories and of rich mineral store. Current excavation of the site reveals deposits of granite boulders and bone, suggesting the area was inhabited as far back as the early thirteenth century – and though there is no evidence of similar foundations in the area, this early show of inhabitation suggests that the site may have been one of many dwelling areas in the region.