The Body Economic (4 page)

Authors: David Stuckler Sanjay Basu

To find out if this explanation was plausible, we turned to the most reliable source of data available from the period: death certificates compiled by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). These data covered 114 cities in thirty-six states over the decade from 1927 to 1937, before and after the Great Depression. The data allowed us to compare what happened to people's health in a variety of places, and analyze the different causes of death to find consistent patterns. Moreover, they allowed us to understand what the trends in life expectancy were before the 1929 Crash, so that we could see if events during the Great Depression were changing preexisting trends or were just part of a broader pattern of public health trends unrelated to the economic crisis.

19

We first analyzed the CDC data to check the accuracy of the public health reports from the insurance industry and the Public Health Service.

F

IGURE 1.1

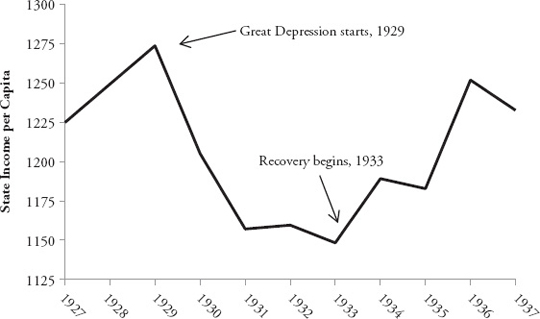

State Income per Capita, US, 1927 to 1937

20

F

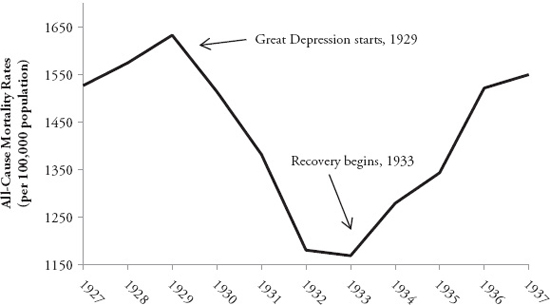

IGURE 1.2

Trends in All-Cause Crude Death Rates, US, 1927 to 1937

21

We were able to confirm that mortality rates fell by about 10 percent during the Great Depression across the United States. As shown in

Figures 1.1

and

1.2

, when the Great Depression started in 1929, average income fell by about one-third, but death rates also began to fall. And when recovery began in 1933, death rates began to rise again.

When we looked at the different causes of death, we found that many complex health changes were occurring at the same time. The most important was a basic trend that we regularly teach our public health students: the epidemiological transition. The epidemiological transition refers to an overall trend in developing societies, in which people die less and less from infectious diseases like tuberculosis but die increasingly from non-infectious diseases like diabetes and cancer. That is, as societies build sewer systems and improve hygiene, live in cleaner conditions and get better access to nutritious food, people experience fewer deaths in infancy and childhood from diarrhea or under-nourishment. Most people live longer and experience more diseases seen in middle and older age.

22

During the Great Depression, most of the changes in death rates apparently weren't being caused by the economic downturn itself. The main causes were due to long-term trends that had already been occurring as part of this epidemiological transition. For example, rates of pneumonia and flu had fallen by over 10 percent, and deaths from cancer and other non-infectious diseases were increasing in parallel over the long termâbefore, during, and after the Depression.

23

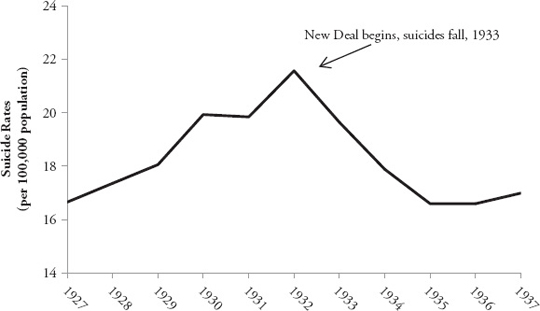

We wanted to know how the Great Depression impacted people's health. Perhaps it just came at a time when other disease rates were changing due to long-term factors unrelated to the Depression per se. To find out, we used statistical models that could filter out the long-term pattern of epidemiological transition from the short-term fluctuations related to the Great Depression. We focused on leading causes of death that have plausible mechanisms linking them to financial problemsâlike the connection between job loss and suicide, or the connection between acute stress and heart attacks. A clear pattern emerged: while overall death rates decreased during the Depression, there were some increases in death rates that were masked by this overall death rate decline. During the Depression, suicide rates saw a significant increase, which was hidden beneath the overall decline in death rates. As shown in

Figure 1.3

, starting in 1929, suicide rates rose by about 16 percent from 18.1 per 100,000 population to 21.6 per 100,000 population at the peak in 1932.

24

Yet when we looked more closely at the data, we saw there were huge variations across the thirty-six states in the CDC database, with suicides rising to different degrees at different times. In Connecticut, suicides spiked by 41

percent, but in New Jersey, they actually fell by 8 percent. Using statistical models, we found that those states, like Connecticut, that had more bank failures had larger spikes in suicides.

F

IGURE 1.3

Trends in Suicide Rates, US, 1927 to 1937

25

However, suicide is a relatively rare cause of death. So even though we found that the economic crash was associated with more people taking their lives, something else was happening to compensate and outweigh the rise in deaths from suicides, leading to an overall decline in death rates during the Depression.

A close look at the data revealed that the increase in suicide was hidden behind a large decrease in death rates from road traffic accidents. Road safety in the early decades of the twentieth century was a barely understood concept; car accidents had become a leading cause of death. Across the US, deaths from automobile accidents in the 1930s exceeded those from typhoid fever, measles, scarlet fever, diphtheria, whooping cough, meningitis, and childbirth combined. But as the Depression took hold, trends changed: the early 1930s saw the first decrease in traffic fatalities in history. Most Americans could no longer afford cars or gasoline, so there was, quite simply, less traffic. When we looked across states, we found the states where the economy slowed down the most were those states where traffic declined and traffic deaths dropped in parallel. This occurred

most prominently in states where road safety was the worst to begin with (in other words, where the risk of death through a traffic accident was the highest). In this case, it seemed, recession was good for people's health.

26

We wondered whether these historical health trends could also apply to the current Great Recession. When we looked at data from the current recession, we found that the evidence from the Great Depression did indeed presage a rise in suicides and a fall in road-traffic deaths during our current recession. Across the United States, during the current Great Recession, suicide rates accelerated above their previous rates. Before the foreclosure crisis that started in 2007, suicides were already increasing at a rate of one per every 10,000 people per year. When the recession began, the rate jumped to five per every 10,000 per year. Overall, we estimated that there was a statistically significant increase of about 4,750 “excess” suicides during the recession, which means that these were suicides that would not have been expected if the recession had not occurred. In the UK, too, we estimated roughly 1,000 excess suicides during the same period.

27

If mental health trends from the Great Depression also applied to the current recession, then we might expect road traffic deaths would also fall. Indeed, US automobile deaths dropped by 3,600 deaths in 2010âreaching a sixty-year low. There was less traffic on the road, especially when wages dropped and gas prices increased during the recession, which statistically correlated to the drop in automobile deaths. Similar reports of reduced traffic accidents came in from Europe. Northern Ireland reported the lowest road traffic deaths on record, experiencing an unprecedented 50 percent decline in fatalities and 20 percent decline in serious injuries. Ironically, this drop led surgeons in London to complain about a lack of organs for transplant surgeries in 2008, because their usual source of supplyâroad traffic deathsâhad dried up.

28

Some observers have interpreted these trends quite favorably. NBC News ran the headline “Good news! Recession may make you healthier.” But such interpretations were missing the bigger lessons from the Great Depression. While the Depression seemed to be a mixed blessing for health, what appeared to be far more importantâboth during the Depression and in the decades that followedâwas how the US government chose to respond to the crisis.

We studied two major policy debates that took place in the United States during the Great Depression. The first was about alcohol. The timing of the Great Depression overlapped with Prohibition on alcohol. The Volstead

Prohibition Act, passed in 1919, mandated that “no person shall manufacture, sell, barter, transport, import, export, deliver, furnish or possess any intoxicating liquor.” The act, however, divided the country. In those states that enforced Prohibition rigorously, people abstained, or were forced to buy alcohol (sometimes quite toxic homebrews of methanol or bathtub gin) at illegal underground bars, speakeasies. But other statesâlike Connecticut and Californiaâwere “wet” throughout. Mixing business failures with alcohol partly contributed to these wet states' higher suicide rates than dry ones. But during the Great Depression, those states with the most stringent Prohibition campaigns experienced one positive trend: significantly fewer drinking-related deaths. Wet states like Connecticut had 20 percent higher death rates from alcohol than did dry states. Thus, Prohibition prevented about 4,000 deaths in dry states from hazardous drinking during the Depression. If it had been applied equally throughout the country, Prohibition would have saved at least 7,300 lives (not that we're advocating a return to Prohibitionâjust gleaning a lesson from it).

29

Perhaps the most convincing piece of evidence that Prohibition protected people from harm was revealed after it was lifted. In the early 1930s, there was public outcry against Prohibition. It was viewed as a source of rising crime, as gangsters like Al Capone operated illicit smuggling from the Canadian and Mexican borders. In addition, Prohibition had also highlighted government interference in people's lives. But the policy argument that led to the end of Prohibition ultimately had to do less with ethics or criminal justice and more with the politics of debt. President Roosevelt wanted to gain votes from the working classes, but also stimulate the faltering US economy by boosting consumer demand. His answer was for people to buy more alcohol and pay a tax on it. As shown in the

Figure 1.4

, alcohol-related deaths during the Great Depression didn't spike until 1933, when Prohibition was repealed. Alcohol-related deaths immediately rose sharply, a trend that continued for the next several decades.

30

But the second policy debate had even greater implications for public health than the politics of alcohol. It centered on the appropriate role of government during an economic crisis.

In the lead-up to the 1932 election, the American electorate was polarized. The economy was in shambles, and total US debt had jumped from 180 percent of GDP in 1929 to 300 percent of GDP in 1932, its highest ratio ever

(that is, until the current recession). A political war raged over austerity, with the country divided between those calling for budget cuts, and others calling for social protection programs to help the millions who had lost jobs and homes during the Depression. Should government step in to rescue the American economy with more spending? Or was it necessary to cut budgets to prevent a further collapse?

32