The Body Economic (8 page)

Authors: David Stuckler Sanjay Basu

Mass privatization, a central plank of Shock Therapy, was supposed to break the Communist Party's influence on the economy. But, in Russia, it simply led to the mass transfer of wealth from the state to the former Communist Party elites, the

nomenklatura

, resulting in a handful of oligarchs and an enormous rise in inequality. Ultimately, it was the common public who lost out. Poverty skyrocketedâfrom 2 percent in 1987â1988 to over 40 percent by 1995. A running joke among families became “The worst thing about Communism is Post-Communism.” In 1992, Russia's vice president, Alexander Rutskoy, denounced Yeltsin's program, calling it “economic genocide.”

29

But not all countries had the same fate. Russia's neighbor Belarus followed a gradualist path. It kept poverty rates below 2 percent during the transition. Its unemployment rate rose in the transition period to a peak of

4 percent but has remained below ever since and, today, has a rate of less than 1 percent. Across the region, the macroeconomic data from twenty-five post-communist countries covering the years 1989 to 2002 revealed that that those countries that implemented rapid mass privatization suffered increased male job losses by 56 percent compared with those that pursued a gradualist path.

Poland's experience made clear that privatization wasn't inevitably bad; rather, the problem was that its rapid pace in other countries had often left firms without strategic owners. Poland, held up as the poster child for Shock Therapy, did liberalize quickly in the early 1990s, but in fact delayed large-scale privatization under pressure from trade unions and angry protesters. In the Czech Republic, too, mass privatization was proposed, and even attempted, but then partly reversed after revolts by unions in the mid-1990s. This slower pace of privatization made a lasting impact on economies. Those countries that privatized their biggest steel mills more slowly were better able to attract foreign investors to take them over. Unlike Russian managers who took over firms and stripped their assets through mass privatization schemes, some foreign investors had a strategic interest in the firms they purchased. Poland was able to attract Volkswagen, along with $89 billion worth of foreign investment between 1990 and 2005. Similarly, the Czech Republic had the French car-maker Renault and Volkswagen Group competing to take over the state-run company, Automobilovézávody, národnÃpodnik, Mladá-Boleslav (now known as Å koda). Volkswagen won the bid in 1991, in a joint-venture partnering agreement with the Czech government. Å koda was once the laughing stock of the car industry, but with Volkswagen's help, it soon became one of the country's most important sources of economic growth, and today sells more than 875,000 cars each year.

31

Transitions weren't painless in any countries of the former Soviet bloc, but they were far less dire and less sustained where the transitions took place more gradually. The Central and Eastern European countries that privatized more gradually to gain foreign investors also had an initial economic recession just like all the former Soviet states, but averted a full-scale economic depression like the one in Russia and the other rapidly-privatizing economies.

Rapid mass privatization was intended to break the Soviet state's grip on the economy, which was perceived by the West as corrupt. Ironically, however, corruption increased after rapid privatization. Many of the insiders who

took over firms in shady privatization deals didn't invest in companies but simply stripped down their assets, sold them, and deposited the money in Swiss bank accounts. To look at what happened to firms, we investigated surveys of managers in 3,550 companies operating in twenty-four post-communist countries. We found that privatization to foreign owners led to increased restructuring of firms into competitive ones, with boosts to both investment and employment. This was precisely the pattern we had seen with Volkswagen in Eastern Europe. But mass privatization to Russian owners wasn't actually followed by the expected economic boom; instead it led to an economy in free fall, with more bribery and asset-stripping than before privatization. The economic impact of mass privatization was to perpetuate economic stagnation, dropping the affected economies' output by 16 percentâa fall equal in size to the countries experiencing the Great Recession of the present.

31

The former Soviet countries' very different economic responses to the collapse of communism had distinctly different effects on the health of their populations. When we compared the data between these countries from 1989 to 2002, before and after transition, we found that rapid privatization carried two chief risks to people's well-being: people losing their jobs and their social safety nets all at onceâa one-two punch.

32

The World Bank, the leading development agency supporting mass privatization, recognized the health risks. The Bank argued in 1997 that “The central premise is that before long-run gains in health status are realized, the transition towards a market economy and adoption of democratic forms of government should lead to short-run deterioration.”

33

Jeffrey Sachs argued that a speedier transition would improve economic growth and, as a result, minimize health damage. But despite such adamant declarations, data from Russia showed a stark picture of human suffering and increasing poverty. As Sachs himself would acknowledge in 1995, the reforms did generate enormous stress and anxiety for the workers, creating winners and losers, but he maintained that the situation would improve in the longer term: “The reforms have surely created a rise in anxiety levels, even if they have not resulted in a fall in actual living standards. In a quite tough sense, economic reform in the early years is a bit like a society-wide game of musical chairs. Once market forces are introduced, a significant proportion of the population must search for new forms of economic livelihood. The result of that search, to

be sure, will be highly positive in the longer term for most of the workers, but the process of change can be deeply upsetting during the transition, and some workers will also end up as economic losers from the changes.”

34

Consistent with the Shock Therapists' predictions, mass privatization led to short-term increases in unemployment and more than 20 percent cuts in government spending, including to health budgets. The consequences were the most severe in the Soviet mono-towns. There, a large rise in unemployment left people without savings to pay for food, housing, medications, or even access to healthcare. Contrary to the Shock Therapists' predictions, however, it also led to an economic depression. Those countries that implemented mass privatization had steeper declines in economic growth, slower recoveries, and more cuts to government spending on healthcare. We found that people living in those countries that pursued mass privatization had substantial drops in access to healthcare.

35

Russia and its southwestern neighbor Belarus serve as an illustrative comparison. Belarus was long part of the Soviet Union, but declared in dependence from Russia in 1991, just before Russia began pursuing mass privatization programs. One leading advocate for the Russian Shock Therapy approach, the Swedish economist Anders Ã

slund, called Belarus a “Soviet theme park” for its resulting slow pace of privatization. But even though Russia was much larger than Belarus, since the 1960s both countries had followed similar economic and mortality trends. The differing policy choices between Russia and Belarus created a type of natural experiment where we could identify the health effects of mass privatization by comparing two countries with similar histories, cultures, and past mortality trends, which differed mainly in their choice of Shock Therapy.

36

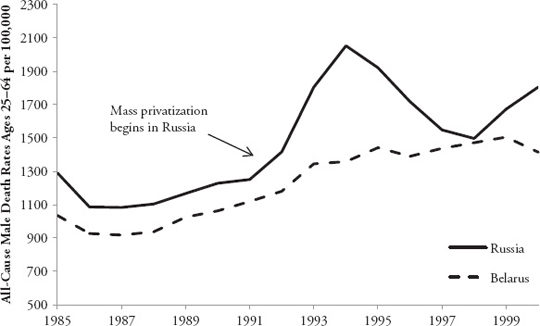

As we can see from

Figure 2.3

, these two countries had experienced roughly similar trends in death rates in the past decade. Russia then underwent mass privatization, selling off over 120,000 companies within two years. On the other hand, Belarus was slow to privatize. Russia experienced skyrocketing poverty and mortality rates, while Belarus kept poverty at less than two percent of its population and continued to have its usual rates of death.

37

This comparative pattern recurred throughout the region. Countries embracing economic Shock Therapyâsuch as Kazakhstan, Latvia, and Lithuaniaâexperienced a sudden and emphatic drop in life expectancy over the course of

five years, while neighboring gradualists like Belarus and Poland fared much better in terms of public health outcomes.

39

F

IGURE 2.3

Mortality Trends in Russia and Belarus

38

But it was possible that factors such as the size of the economy could be confounding the picture. We used statistical models to adjust for the differences in a country's economic performance, its past economic crises, its experience of ethnic and military conflict, its current level of development, the portion of people who lived in cities, other Shock Therapy policies including liberalization of markets, the level of foreign direct investment, and other social and economic factors that could come into play in twenty-four post-communist countries. Even after these multiple control variables, we found that countries such as Russia and Kazakhstan, which had implemented radical mass privatization schemes, had experienced, on average, an 18 percent rise in death rates after the policy went into effect, which was not seen in the more gradualist privatizers like Belarus and Poland. As a check on the validity of our findings, we looked at causes of death that should not fluctuate rapidly because of austerityâsuch as lung cancer, which would take several decades to develop. There we found no effect. But we did find that mass privatization increased male suicides by five per 100,000, heart disease by 21 per 100,000, and alcohol-related deaths by 41 per 100,000. Overall, mass privatization was correlated with a significant drop in life expectancy by two years.

40

This short-term pain was, of course, foreseen by the Shock Therapists. But they had predicted that short-term suffering would lead to long-term economic growth, which would compensate for the human costs. If that were the case, it could be argued, the sharp increase in mortality could be seen as collateral short-term damage en route to a brighter future. A general rule of thumb is that “wealthier is healthier”: people with larger incomes are more able to pay for healthcare and lead healthier lives by living in cleaner and more hospitable environments, eating more nutritious food, and taking up residence in safer neighborhoods. So was the economic benefit of Shock Therapy to the Russian people sufficient to neutralize the short-term rise in death rates? That was, after all, the theory of the Shock Therapists. In other words, did short-term pain lead to long-term gain?

41

When we looked at the actual data, we unfortunately found that mass privatization did not speed up the economy. Quite the contrary, it led to a drop in GDP by a further 16 percent, making the full impact of privatization about equivalent to a 2.4 year loss in life expectancy.

42

Eventually, even some of those who had initially advocated Shock Therapy came to acknowledge its negative health consequences. Milton Friedman later admitted an error. “In the immediate aftermath of the fall of the Soviet Union, I kept being asked what the Russians should do. I said, âPrivatize, privatize, privatize.' I was wrong. [Joseph Stiglitz] was right.”

43

Of course, not everyone was pleased by the finding that mass privatization was correlated with a large rise in deathsâpredictably, the former advocates of Shock Therapy rushed to defend their actions. We published a peer-reviewed paper on the health effects of Shock Therapy in January 2009 in the British medical journal The

Lancet

, and the week after it came out, Sachs attributed Russia's dramatic increase in poor health to unhealthy diets rather than the impact of Shock Therapy. But Russian diets high in red meat and saturated fat had been on the increase since the 1960s, and had not suddenly changed for the worse during the few years of the early 1990s. Others who had recommended mass privatization to the Soviet bloc wrote that the crisis might have been from “disease stemming from some past exposure to pollution.” Yet no major pollution exposures could account for a rapid spike in deaths concentrated among only the young men. Searching for further explanations, other economists then claimed that the alcohol deaths were just from the ending of the Gorbachev alcohol prevention program, but neglected to mention that the

program had ended long ago, and the number of people whose lives were saved were vastly outweighed by the rise in deaths after Shock Therapy.

45