The Body Economic (11 page)

Authors: David Stuckler Sanjay Basu

When we looked at the Thai health system's data, we found that condom distribution to brothels dropped from upwards of 60 million condoms in 1996 to 14.2 million in 1998. As a result, Thailand's HIV prevention program began to falter. The rate of AIDS patients reported in Thailand increased from 40.9 per 100,000 in 1997 to 43.6 per 100,000 population in 1998. The pharmaceutical budget for preventing mother-to-child transmission could only meet 14 percent of the estimated total need after the cuts. The number of orphans with HIV rose from 15,400 in 1997 to 23,400 in 2001. Half of those infected children who received no medical treatment died by the age of five.

29

F

IGURE 3.1

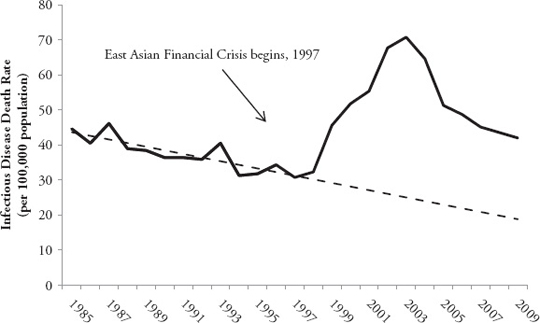

Thailand's Large Increase in Death Rates from Infectious Diseases

28

Thailand's progress in preventing infectious diseases such as HIV was all but erased, as shown in

Figure 3.1

. Between the 1950s and 1996, infectious disease deaths had been falling at a rate of 3.2 deaths per 100,000 population per year. This progress began to reverse in 1998, when infectious disease death rates started to rise at a rate of 7.6 deaths per 100,000 population each year. The main cause of the rise in deaths was untreated HIV, and its complications, pneumonia and tuberculosis.

30

To fill the gaping holes in Thailand's public health system left by austerity, medical volunteers like Sanjay had stepped in to help support Thailand's HIV prevention and treatment programs. They were able to save some lives. But for othersâlike Kanya, the sixteen-year-old girl from Kanchanaburiâthey were too late.

In contrast to Thailand, Malaysia chose to ignore IMF advice to cut budgets, and instead increased real healthcare spending by about 8 percent in 1998 and 1999. The boost to healthcare funding translated into a rise in patients who were treated in the public health system by about 18 percent. The

increased HIV control budget enabled Malaysia to introduce a mother-to-child transmission prevention program, modeled on Thailand's. In other words, just as Thailand's flagship public health programs were being wiped out, Malaysia put identical ones into place. And during the crisis, there was no significant rise in HIV in Malaysia even as control of the disease began to falter in Indonesia and Thailand.

31

Meanwhile, the IMF's partner organization, the World Bankâwhich oversees social well-being and poverty reliefâevaded questions from reporters and researchers about how health had been affected by the crisis and the IMF's programs in the region. In South Korea, the Fund became known as the “Infant Mortality Fund,” because the infant mortality rate rose in association with the Fund's austerity program. When asked, “Has health worsened in Indonesia?” Bank officials replied that it was “difficult to get a complete and consistent picture of the health impact of the crisis and the effectiveness of policy responses. Some standard barometers suggest catastrophic results were averted. For example, infant mortality rates seemed to have continued a âdownward trend'.” Yet an analysis published in the prestigious British medical journal The

Lancet

by independent health researchers found that the Bank's reports were “inaccurate” and “groundless.” The Bank, usually meticulous in citing data sources, failed to cite any for its assertion that infant mortality decreased. In reality, the Indonesian Central Statistics Bureau reported in the United Nations Human Development Report that infant mortality had increased, rising in twenty-two of its twenty-six provinces of Indonesia by an average of 14 percent.

32

Despite these results, not all IMF programs were disastrous. A few IMF measures helped prevent disease, mostly by reducing alcohol use. In 1998, to meet the IMF demand for budget surpluses, Thailand's government was forced to increase sales taxes on alcohol. According to the National Tax Administration data on alcoholic beverages, the reforms worked: consumption of alcoholic beverages fell by 14 percent over two years.

Recession in East Asia did not have to spell a health disaster. But massive budget cuts corresponded to real rises in hunger and forgone access to doctors and clinics. Cuts did not just occur to a few poorly performing programs, but were made without regard for Thailand's internationally acclaimed HIV program. The health disaster that followed set back progress in fighting hunger and infectious diseases. East Asia had become the next textbook case

of what can happen when austerity politics are placed before people's health. As in Russia, the large dose of austerity harmed the ultimate source of East Asia's progress: its people.

In the years following the crisis, an economic divide emerged between IMF borrowing-and non-borrowing countries. Malaysia, having rejected the IMF's directives in pursuing its own path of state intervention, avoided mass misery and suffering, and accelerated its economic recovery. Malaysia was, in fact, the first country in the region to experience economic recovery. Although average incomes declined in 1998, Malaysia's recovery began the following year. Food prices had risen 8.9 percent in 1998, but two years later back to a mere 1.9 percent above their pre-crisis levels. South Korea was an intermediate case; as a bigger economy than Malaysia's, with greater government spending prior to the crisis, it had more “policy space” in which to maneuver and could better negotiate with the IMF to avoid the most painful budget cuts. It was the second nation to recover after Malaysia.

33

In 2000 Joseph Stiglitz summed up the role of the IMF in the East Asian Financial Crisis: “All the IMF did was make East Asia's recessions deeper, longer, and harder. Indeed, Thailand, which followed the IMF's prescriptions the most closely, has performed worse than Malaysia and South Korea, which followed more independent courses.”

34

Ironically, of the four countries examined here, only Malaysia was able to meet the IMF's ultimate economic targets even though it didn't participate in the IMF program. Malaysia ended up with a budget surplus in 1997, even though it was the only country that avoided cutting social protection spending.

35

Those within the IMF were beginning to admit their errors. In a confidential report leaked to the

New York Times

, IMF staff members agreed that their lending conditions worsened the crisis. “Far from improving public confidence in the banking system,” the report stated, “[our reforms] have instead set off a renewed âflight to safety',” referring to continued withdrawal of investment from the region that prompted banking closures. In other words, the IMF's programs had worsened the sense of panic, not only because of its dire warnings which scared investors, but also because high interest rates and budget cuts slowed down the economy.

36

The natural experiment in East Asia had striking results. When Malaysia refused to cut its public health budgets, immunization programs and food assistance projects were preserved, and the country did not experience a marked rise in malnutrition and HIV, unlike its neighboring countries that slashed health budgets. As one UNICEF report concluded, “In Malaysia, unlike in Indonesia, the Republic of Korea and Thailand, there is little doubt that the social impact of the crisis has been contained.” An independent analysis of the data by Australian public health experts summarized the situation: “These results strongly suggest that social protection programs, adapted to meet the needs of the most threatened population groups, are necessary and important tools to protect against the adverse effects of an economic crisis on health and health care.” Researchers at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health agreed, concluding that “social protection programs play a critical role in protecting populations against the adverse effects of economic downturns on health and health care.”

37

Ten years after the East Asian Financial Crisis, the worldwide Great Recession hit Indonesia. It brought the country an opportunity to learn from its mistakes; this time the Indonesian government increased some subsidies to poor people. Thus, the poor could still afford cooking oils amid rising food and fuel prices in 2008 and 2011 (which were due in part to the movement of investors out of mortgage-backed securities and into food commodities investments).

38

It was only in this current Great Recession crisis that the IMF issued a formal mea culpa for its shortcomings during the East Asian Financial Crisis. In October 2012, the Fund admitted that the economic damage from its austerity and liberalization recommendations in East Asia may have been as much as three times as great as it had previously assumed. While the IMF had predicted its measures would grow Indonesia's economy by 3 percent, the economy actually contracted by 13 percent. The director of the Fund issued a formal apology. Such apologies were of little use to the millions of lives destroyed by the IMF's “help.” Many East Asian countries will not go back to the Fund if they can avoid it; these countries together have amassed $6 trillion in savings accounts filled with foreign exchange investments in case of another economic downturn. “People learn from what happened in the past,” said Indonesia's Trade Minister Gita Wirjawan. “Certainly what we went through in 1998 was painful.

I lived through that, and hopefully the difficulties we went through served as lessons.”

39

The lessons of historyâthe New Deal, Shock Therapy in Russia, and the IMF programs in the Asian Financial Crisisâare clear. They present us all with a clear decision. Will we continue to balance budgets on the backs of the most vulnerable members of society? Will tens of millions of people like Olivia in California, Dimitris in Athens, the McArdles in Scotland, Vladimir in Russia, and Kanya in Thailand have to suffer for misbegotten austerity programs? Or will we finally recognize that economic health and human health go hand in hand?

THE GREAT RECESSION

4

GOD BLESS ICELAND

“Gud Blessi Is'land.”

The three words appeared in blocked white letters on television screens all over Iceland on October 6, 2008.

“Fellow Icelanders,” a voice began. “I have requested the opportunity to address you at this time when the Icelandic nation faces major difficulties.”

1

Most people in this island nation of 317,000 refer to each other by their first names. This was Geir Hilmar Haarde, the prime minister, speaking. The block letters on the screen were replaced by his image: he stood behind a cluster of microphones, wearing his signature blue blazer, next to the country's flag. His cheeks sagged with worry.

“There is a very real danger, fellow citizens, that the Icelandic economy, in the worst case, could be sucked with the banks into the whirl pool and the result could be national bankruptcy,” he said, adjusting his glasses nervously.

2

The stress was palpable. In 2008, financial crisis had spread like a virus across the Atlantic, from the American mortgage crisis to the European stock market, and now to this tiny island nation. In December that year, The

Economist

reported that “Iceland's banking collapse is the biggest, relative to the size of an economy, that any country has ever suffered.” The crisis came as a massive shock to the peaceful nation of Iceland, and many commentators predicted doom. All its biggest banks failed, the stock market crashed by

90 percent, and investments worth nine times the country's annual economic production disappeared within one week in October 2008. The Icelandic Public Health Institute asked local journalists to write more positive stories in an effort to curb the risk of suicide. As Bloomberg financial news reported, “This was no postâLehman Brothers recession: It was a depression.”

3

As a result, Iceland's people now faced their biggest health threat since World War II. With a large rise in debt, the universal healthcare system faced bankruptcy. The entire system was publicly funded and run; there were virtually no private hospitals, clinics, or insurance. So if government funding dried up for the health service, people's access to healthcare would be directly impacted. Another threat was that if Iceland's currency, the krona, depreciated, the cost of importing essential medicines would soarâmaking medicines unaffordable at a time when government budgets were already overstretched. Adding to the risks, the possibility of major job losses and home foreclosures threatened to provoke depression, suicides, and heart attacks, placing pressure on Iceland's public health service.

4

Geir continued his speech. “I am well aware that this situation is a great shock for many, which raises both fear and anxiety. If there was ever a time when the Icelandic nation needed to stand together and show fortitude in the face of adversity, then this is the time. I urge you all to guard that which is most important in the life of every one of us, protect those values which will survive the storm now beginning.”