The Body Economic (14 page)

Authors: David Stuckler Sanjay Basu

In fact, we found that people increasingly reported “positive” symptoms in spite of the economic crisisâfor example, that they more frequently woke up feeling fresh and rested. These positive symptoms seemed to be explained by people working less, and having more leisure time. To double-check the quality of these survey data and make sure they were credible, we took the data to Cambridge University, where depression expert Felicia Huppert evaluated it and replied, “These are beautiful data!”

All of this corresponded with the first UN World Happiness Report in 2012, presented by the “happiness economist” Richard Layard. In terms of

“gross national happiness” and “the happy index,” among other measures, Iceland had maintained its position as number one in the world. It had both the highest quantity of “positive affect” (good moods) of any country surveyed, in spite of the ongoing economic crisis.

32

So how had Iceland managed to remain happy and healthy despite a massive economic meltdown?

A team of Icelandic economists analyzed data from around the country and reached the same conclusions as we did from our studies of the Icelandic Health Survey. They found that some of these positive trends, like having more free time, were likely to have been linked to the recession itself. The Icelandic Health Survey also contained questions about people's diets, as well as their drinking and smoking behaviors and other major public health risk factors in 2007 and 2009. The research team found that, during the period of crisis, Icelanders reduced their frequency of smoking, heavy drinking, and consumption of unhealthy fast food. These changes were in part driven by changing prices and lower incomes. When prices go up, people tend to buy fewer cigarettes and less alcohol, and eat at home instead of in restaurants. Icelanders also got more sleep than before the recession, an increase linked to less time at work. While the study wasn't able to show decisively that the recession

caused

these changes in health behavior, it did find further evidence that health statistics were moving in a positive direction during the recession.

33

Health appeared to improve, in part, from a better diet and lower alcohol use. In October 2009, McDonald's pulled out of the country, blaming Iceland's “unique operational complexity,” as the price of tomatoes and onions skyrocketed when the krona's value fell. “For a kilo of onions imported from Germany,” reported one local franchise own er, “I'm paying the equivalent of a bottle of good whisky.” But after McDonald's left, people increasingly turned to cooking at home with local foods instead of going out for imported fast food, with the result that the consumption of locally caught fish also rose as fast food consumption fell. Indeed, the eventual economic recovery in Iceland was driven by in part by the return of the traditional fishing industry, leading in due course to an export boom.

34

Iceland also upheld its state monopoly on alcohol. It rejected the advice of the IMF to privatize alcohol stores as a means for boosting the economy. In the 1980s and 1990s, it was difficult to find spirits on sale. Iceland's combination of high alcohol prices and tight regulation, at a time when the imports

of spirits became prohibitively expensive because of the falling currency, made alcohol a costly option for coping with stress.

35

So, overall, some of the key factors in the recession actually seemed to keep people healthier during the economic crisis. But what about the democratic referendumâdid deficit spending, and delayed payment to IceSave's investors, critically harm the future economy and public health of Icelanders?

Iceland took two important steps that protected people's health and well-being. By first rejecting the IMF's plan for radical austerity, it protected a modern-day equivalent of the New Deal. In the decades before the recession, Iceland had put in place a strong social protection system. After the public referendum to maintain that system, the government bolstered supports to those in need even further. In 2007, Iceland's government spending as a fraction of GDP was 42.3 percent. This increased to 57.7 percent in 2008 and has remained about ten percentage points above pre-crisis levels at the time of this writing. This increase didn't lead to inflation, runaway debt that has been impossible to pay back, or foreign dependencyâthe predicted disasters that austerity advocates claim will result from stimulus programs.

36

Iceland didn't balance the budget through massive cuts to its healthcare system. While its currency devaluation meant the National Health Service had less money to import drugs and medicines, the government offset this threat of unaffordable pharmaceutical imports by increasing health budgets between 2007 and 2009âfrom 380,000 kronas per person to 453,000. The result was that essential services were protected, so that patients did not lose access to care.

Iceland also maintained its social protection systemâprograms to help people maintain food, jobs, and housing. It boosted key labor market programs to help people get back to work if they were recently unemployed. It implemented a new policy allowing small and medium firms to apply for debt relief; if they could show positive cash flow in the future, the debt or part of it would be forgiven. As a result, employers were not only able to retain employees but to hire new ones during the crisis. “The government has substantially boosted expenditure on public employment services to offer appropriate job matching and training services,” reported the Paris-based technical economic institute, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The OECD had aligned itself with the IMF's advice for austerity, but strongly recommended it be done with a “human face”âto maintain social protection.

37

Overall Iceland's social protection spending rose from 280 billion kronas ($2.2 billion) to 379 billion ($3 billion) kronas, from 21 percent of GDP to 25 percent of GDP between 2007 and 2009âa rise that went beyond benefits to the unemployed and healthcare coverage. The additional spending also helped fund a series of newly instated “debt relief” programs. For example, to homeowners who had negative equity, the country wrote off debt that was above 110 percent of the property value, and offered money to those who qualified as poor to help reduce mortgage payments. This was a radical step. Other countries hit by the Great Recession were not so supportive of their citizens. In Spain, for example, even when people were evicted from their homes and declared bankruptcy, they had to continue paying their housing debts and many became homeless. In Iceland, by contrast, the debt relief programs helped people stay in their homes, and there was no significant increase in the number of homeless. The number of houses receiving income support rose from about 4,000 in 2007 to 7,000 in 2010. Thanks to these kinds of supports, the percentage of house holds at risk of poverty was unchanged despite Iceland's crisis. Had these social protection supports not been maintained, a third of Iceland's population would likely have been plunged into poverty. Iceland's Ministry of Welfare also implemented a “Welfare Watch” group, which would publicly respond to the government about how people's health and well-being were being impacted by the downturn. Many of their recommendations were implemented.

38

In addition to keeping the safety net, the other critical factor in Iceland's response to the crisis was national solidarity. Despite early tensions between wealthy debtors and the rest of the population, the national referendum sparked a new period of unity. The people of Iceland felt that they were all experiencing the crisis together. Iceland maintained its position as having some the highest rates of “social capital” in Western Europe: meaning that it's common for people to have strong groups of friends in their neighborhood, at work, and at church. Unlike the Russian situation where people were left in isolation and desolation in mono-towns from the Soviet era, the Icelanders had strong community networks. When we arrived at the country's airport, we were surprised that practically everyone knew each other on a first-name basis. People regularly went to saunas and steambaths with their families after workânot only making it easier to relax and alleviate stress, but building a sense of community and togetherness (if also a bit of indecent exposure)âall

which may have contributed to a heightened spirit of democracy in a time of crisis. And Iceland's level of inequality, which had jumped prior to the crisis, fell sharply after the economic collapse to levels on par with its Nordic peers.

39

The collapse of the Icelandic economy, then, did not lead to much of a health crisisâin fact, the impact of the crisis as a whole didn't even make for an exciting movie. When the reviews rolled in for Helgi Felixson's documentary

God Bless Iceland

, critics carped; one complained that there was “not enough mustard” for the movie to build much drama. The film's problem, from a theatrical standpoint, was that Iceland hadn't fallen apart as predicted.

40

The response of Iceland's government to the crisis reminds us how important it is to safeguard democracy, even at a time when extraordinary responses are needed. Even if hard decisions need to be made, a bitter pill is easier to swallow if you administer it yourself.

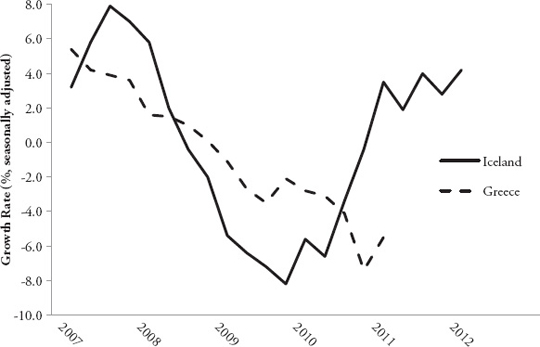

It was Iceland's heavy “financialization” of its economy during the 1990s and early 2000sârelying on high-risk investments by banks, rather than on industries that actually produced real, useful goods and services, or developed new technologiesâthat put its people at risk in the first place. But when managed with care, the crisis became an opportunity for the Icelandic people to rediscover their values, enabling the nation to rebuild an economy that is now thriving on its fundamentals. In 2012, Iceland's economy grew 3 percent and unemployment fell below 5 percent, while the UK's economy, under the Conservatives' austerity programs, continued to sink. In June of that year, Iceland made repayments on loans, ahead of schedule. Fitch Ratingsâone of the big three ratings agencies, along with Standard and Poor's and Moody'sâhad initially called Iceland's economic choices an “un-orthodox crisis policy response,” but in early 2012 it restored the country's high investment status, rating Iceland as “safe to invest.”

41

Even the IMF later admitted that the unique Icelandic approach led to a “surprisingly” strong recovery. The IMF's reform proposals, followed by a retreat on its previous position, was history repeating itself. This time, in its ex-post evaluation, it concluded that one key lesson was that “social benefits were safeguarded in line with the authorities' post crisis objective of maintaining the key elements of the Icelandic welfare state. This was achieved by designing the fiscal consolidation in a way that sought to protect vulnerable groups by having expenditure cuts that did not compromise welfare benefits and raising revenue by placing greater tax burden on higher income groups.”

While couched in bureaucratic language, the admission that social protection programs were vital to economic recovery and well-being was a revolutionary statement for the IMF.

42

While these reports emphatically validated Iceland's approach, not everyone was pleased. The UK and Netherlands ramped up their pressure for Iceland's people to pay back IceSave's private investors with public tax dollars and implement strict austerity in Iceland. In April 2011, the Icelandic people turned out for another vote. This time, 60 percent of the population rejected a deal between Iceland and its main creditors, the Netherlands and UK, under which the IceSave investors would be immediately paid back. As the

Financial Times

reported, Icelanders had “put citizens before banks.” Larus Welding, the former bank chief of Glitnir, was later convicted of fraud as part of national reconciliation. Iceland's president, Ãlafur Ragnar GrÃmsson, said, “The government bailed out the people and imprisoned the bankstersâthe opposite of what North America and the rest of Europe did.” Iceland's banks had been deemed “too big to fail,” and the government let them fail. The consequences were clear in the data showing Iceland's successful recovery while most of the rest of Europe continued to suffer.

43

At the time of this writing, the terms of austerity plans to pay back Ice-Save's creditors are making their way to international courts. Prosecutors in the UK and Netherlands sued the Icelandic government to speed up debt repayment. In the meantime, it appears that avoiding a deep austerity program, and making smart investment choices in critically important social protection programs, has spared lives. So even though Iceland had allowed its bankers to engage in reckless betting with people's money, citizens stepped in to determine how to clean up their mess. They chose wisely, protecting people from further harm, while simultaneously restoring the economy to growth.

The people of Iceland are also learning lessons from the IceSave disasterâtaking proactive steps to ensure another crash never happens again. In July 2011, twenty-five of the country's citizens put together a crowd-sourced constitution designed to give the people greater control over their natural resources and break up cronyism between the banks and political elites. Using social media applications, all Icelanders could respond to six questions about constitutional changes. On October 2012, two-thirds of Iceland's population voted to replace the Icelandic constitution with a new one based on this crowd-sourced constitution.

44