The Bolter (19 page)

Authors: Frances Osborne

Unfortunately, despite his efforts to keep the divorce out of the press, it had made the front page of the

Washington Post

.

DIVORCE RUNS IN FAMILY

, ran the headline.

4

The article raked over not just Euan and Idina’s divorce but also Muriel’s divorce from Gilbert and Gilbert’s subsequent divorce from his second wife. It was not a good beginning to Euan’s task in Washington.

Meanwhile, on the last Thursday in March, Idina married Charles Gordon at the Chelsea Register Office. It was a small wedding. She had three witnesses: a friend called Rosa Wood, the future collector of Surrealist art Charles de Noailles, and Rosita Forbes.

Within a week the newlyweds had sailed for Kenya.

Idina had bolted.

BOOK TWO

Kenya—Happy Valley

Chapter 13

I

n April 1919 Idina and Charles crossed to France and took the train south to Marseille, where they boarded a boat for Mombasa in search of a new life and adventure. Their plan was to buy a farm, build a home, and create a rural idyll on the other side of the world. Where Idina was going was new. Her husband was new. She, however, was as battle-scarred as the Europe she was trying to leave behind. She had neither fallen sufficiently out of love with her old husband, nor sufficiently in love with her new one. And she had had to give up her children.

Mombasa was achingly hot when Idina and Charles arrived. The turrets of thick purple baobabs bulged at them along the seafront, their outlines blurred by the clouds of dust. Oxen, with their sleepy lamplike eyes and wing-mirror horns, loomed around the corners as silent motorcars. Idina and Charles rattled along the streets on the town’s trolleys: a bench for two balanced between an awning and a platform on tramlined wheels, pushed by barefoot Africans.

On the slopes leading down to the seafront the trolleys careered off, building up enough speed for a longed-for rush of air to blast away both the heat and the stench of dried shark curling up from the boats below.

Down on the ocean’s edge they drank at the Mombasa Club with its white plaster walls and greenish tin roof, the bloodstained sandstone walls of Fort Jesus and its inmates at their elbow and an endless sea ahead. They lolled on the upper floor’s veranda, catching the sea breeze,

ice-laden gin and tonics at their fingertips. Soon it would cool down, when the rains came.

Mombasa was a frontier town: shops on the ground floor and living accommodation girdled by dark-wood verandas on the first. It was the entrance to the British East Africa Protectorate, an area that stretched a couple of hundred miles north up the coast and six hundred miles inland. Sixty years earlier a British explorer, John Hanning Speke, had walked that far through the German-controlled land to the south and discovered the great gleaming Lake Victoria in Uganda. The lands around the lake were promisingly fertile and Lake Victoria was also the source of the River Nile. The British government saw control of both the Nile and Egypt as vital to keeping open the Suez Canal, which was the gateway to its empire to the east, and so decided to create its own route there. The area north of the German territory had so far been untouched in the scramble for Africa by European states: the tribes were inhospitable, much of the area was desert, and the air was thick with disease-bearing insects. The British were undaunted. The route in was through the port of Mombasa.

The British way into a new land was Church and trade: the missionaries wandered in with their Bibles and the Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEAC) was set up to bring the business in. Neither, however, made much progress. The tsetse fly was so prevalent in this part of East Africa that it proved impossible to use animals to transport supplies inland. By the 1890s the IBEAC was heading toward insolvency. In 1895 the British government took direct control of the region, in the process bringing a solution to the problem of transport. It would build a railway stretching the whole six hundred miles from Mombasa to Lake Victoria: the tsetse fly would be overcome. Five years and 5.5 million pounds later, the railway was complete. The pride of British East Africa was just under six hundred miles of gleaming iron, single track and a long, round, smooth monster of an engine, gulping wood and belching smoke. This was the Uganda Railway, called the Iron Snake by the Masai cattle herders through whose homelands it slunk. Before the rains came, Idina and Charles boarded the noon train. Their compartment was a square loose box with no link to its neighbors, the windows were dark with stifling mosquito screens, the pinpricks of ventilation choked with red dust. And off they went through the palm trees and slowly up, up, up to grassy highlands as scrub-ridden and green as a British hill. At teatime the train paused for toast and rhubarb jam and, as the sun set at an equatorial six sharp, the white-tipped

Mount Kilimanjaro hovered beyond the screens. At dinnertime they stopped for a curry and were besieged by insects, while their beds were made up with crisp linen sheets. At dawn jugs of condensed engine steam for shaving and cups of tea appeared beside the line in the hands of waiters in white suits and red fezzes.

They clambered out of the Iron Snake at Nairobi. The town had started as a tented camp at Mile 327 of the planned Uganda track. By the time the railway line had reached it, in May 1899, many of those who had built it were too ill to travel further. A few miles ahead the earth split into the Rift Valley, a great crack in the earth’s surface running the length of Africa. It was a vast plain of flat-bottomed canyon, channeled out of the highlands and framed on either side by vertical cliffs thousands of feet high. To build a railway down the escarpment was, to say the least, challenging, even for those who were well. The railhead paused. Headquarters were established. The Railhead Club, colonialism on wheels, pegged its guy ropes to the ground. Tents and shacks spread over the plains. In the rains groundsheets sank into a black-soil malarial swamp. In the dry season the earth cracked, its debris flying up at the touch of a heel or hoof, coating every inch of flesh and fabric in a second skin of African dust. Eventually the railway builders moved on. The town, however, stayed.

Once Idina and Charles’s car had been rolled off its wagon at the back, its earth-covered canvas peeled off, engine tinkered with and recoiled until it was purring again in a haphazard way, they drove a couple of miles out of the center of town to a newish club, the Muthaiga Country Club. It had opened only a few months before the war had begun and real time had halted. Muthaiga was long, low, and colonial. Its external plaster walls were painted a desert pink and surrounded by a garden at first glance classically English. The grass, however, was just a little broader, the flowers brighter, and the vegetation as lush as any in the greenhouses at Kew. Inside, dark-wood floors and window frames enclosed floral-print English armchairs and African hunting spoils, including an entire stuffed lion.

Before Muthaiga opened, the British and European gentry abroad had stayed at the Norfolk Hotel, in the center of town. When Muthaiga arrived, all those who were members of suitably exclusive gentlemen’s clubs “back Home” migrated to the welcoming restrictions of the new establishment. There were rooms in the main building surrounded by a lush garden, perfect for newlyweds with nowhere else to go.

Idina and Charles did not, as yet, have a farm, a

shamba

as they called

it there. They hoped to be allotted one in the British government’s land raffle to be held in a few weeks’ time. The Uganda Railway had created a secondary industry of farming alongside its tracks, from where those legendary three African harvests a year could be rolled downhill, onto the Iron Snake, and taken straight to a waiting steamship in Mombasa, for delivery to a hungry Europe. All that was needed was farmers, and a great many of them, for no fewer than two and a half million acres needed tending to. When the war had ended, Britain had started to overflow with trained soldiers in search of a new life. The British government, in the manner of a parish church fête, decided to hold a lottery to distribute farms in the East African Protectorate to these war veterans; given the unwillingness of the indigenous people to surrender their lands, all the better, went the thinking, that the territory should be occupied by men who knew how to handle a rifle. Anyone who had served six months in the armed forces could enter. That included Charles Gordon.

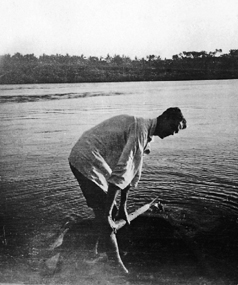

Idina’s second husband, Charles Gordon, in Kenya

The farms being handed out ranged from 160-acre plots, which were free of charge, to larger farms of 3,000 acres for which payment was to be made. Each was numbered and applicants had to list these in order of preference. When a man’s, or indeed a woman’s, name was drawn, they would be allotted the farm highest on their list that was still available.

The raffle was set for the middle of June, after the long rains. That gave Idina and Charles two long, wet months to draw up their choices. The rains had already started in Nairobi and in the farmlands up-country, and the mud tracks leading down from the farms to the railroad had dissolved into deltas. The best research would be here, in town: in the wood-paneled bar of Muthaiga, where the chaps were gentlemen, or ought to be, and in the glitzier environs of the Norfolk bar, open from eleven in the morning, where even the faster sort of fellows could ply their trade. Those piling out of Europe in search of the new had been both mentally and physically toughened by the war. Some had come here to find farmwork, either on their own land or as crop experts or cattle herders. Others, all too familiar with handling a gun, came to be hunters—men who could lead tourists on long safaris into the bush.

SEVERAL LONG, BAR-FUELED WEEKS LATER

Idina and Charles followed the crowds into Nairobi’s Theatre Royal, a parapeted and colonnaded stone building that functioned as a meeting room as well as a music hall. On the stage two large tin drums turned, containing the name of each raffle entrant. There were two thousand names and fewer than fourteen hundred farms. Name by name the would-be farmers were drawn out and their list of choices produced. Idina was lucky. Charles was called, and he was called early. They had won one of the three-thousand-acre farms. It was up in the Highlands, on the edge of the Aberdares, a range of high, rolling hills overlooking the grassy, antelope-covered plains of the Rift Valley and teeming with wildlife themselves. At the foot of the hills, as the slopes softened into a plateau, was rich, thick farming soil.

Idina and Charles hired a Somali head servant to run their home, packed tents, tables, chairs, cooking equipment, lamps, candles, and matches, and loaded them, along with a couple of horses, onto the next train heading west. At nightfall they tumbled off the train at Gilgil, a cowboy town on the edge of the Rift Valley escarpment halfway between Nairobi and Lake Victoria. A few low-built shacks and corrugated-tin huts lined a railway siding, surrounded by a crowd of local Kikuyu and Masai tribesmen who had gathered from hill and valley to meet the train. The head servant hired a guide, porters, hut builders, and a team of general servants, and pitched camp for the night. The following morning Idina and Charles’s belongings were tied onto a couple of carts and oxen were harnessed at the front. They

mounted horses and set off uphill. By nightfall they had reached their land. Ahead of them the Aberdare Hills rolled dark green in the setting sun; from them fell ice-cold brooks, swollen by the recent rains. Below these their virgin farmland glowed with luminescent grass and thick, red soil. This was Idina’s new home.

Twenty miles from the Equator, the land northeast of Gilgil should have been arid, yellowed and browned by the sun until the grass crackled and the mud powdered. But eight thousand feet above sea level the rules of climate—for a start—changed. The altitude took the land right up to the freezing fingertips of the clouds. At night, when it was cool, it was very cool, those cloudy fingertips wrapping themselves around each blade of grass. At dawn the sun arrived to chase off the cold, damp night air and evaporate the freezing dew into a chilly mist. By midday the heavy African sun had illuminated the sky a quivering blue. Its glare bent the air and seared napes and noses, cheekbones and wrists. Then, when it had coaxed the flowers out of their buds but before it had sucked every inch of moisture from them, the sun started to dip below the horizon and those fingers of cold air and all their soggy, green-tinged moisture worked their way back in.

It was an earthly paradise. The landscape was genuinely familiar, indeed almost Scottish. Lumpy green grass spread over gentle slopes. The air hummed with the persistent buzz of insects. A burn of a slender river—the Wanjohi—gurgled and danced over flat stones. Bushes burst from the ground in a profusion of pale, paper-thin leaves and dark, rubbery plants. Tall, gray-barked trunks rose bare to a high crown of shortening branches covered in thousands of tiny leaves. Bristling bushes spiked up in between.

Yet, in a very un-Scottish way, every growth was magnified in color, size, and even intensity. Each bush throbbed with creatures large and small. Elephant, giraffe, and antelope rustled through, breaking out and swaying across open land. Leopard and monkey hung from trees reverberating with birdsong. The insect hum was deeper, lower, and more menacing than back Home. And rather than the vague, sweet scent of rolled lawn, the air was filled with a pungent but compelling smell of animal dung mixed with freshly picked herbs. At night, when Idina and Charles sat outside, they were surrounded by lookouts watching for wandering elephant, big cats, or buffalo—whose long, curved horns were the most lethal of all.