The Bolter (17 page)

Authors: Frances Osborne

Three weeks after Euan had returned to France, he received a letter from Idina: “An important letter,” he wrote. But, however poor the state of his marriage, just three weeks after the best part of four months back in England, there was little that Euan could do about it now.

Even for those who hadn’t been home, leave was thin on the ground. For the next three months everyone was kept busy with orders for “desperate schemes” and “death-rides” being proposed and most of them, “Thank God, cancelled.” But not all. Stuck on the pit-scarred Somme battlefield, the ways ahead and behind jam-packed with troops and unable to move off the narrow tracks that divided the shell holes and trenches, the Life Guards found themselves sitting targets for the enemy: “heavily shelled for 35 mins. 2 OR hit: horses stampeded and

several killed.” They had lost several officers and men the day before when the Brigade HQ had been shelled. Now half of Euan’s horses were gone and he didn’t even have a saddle left. But at last the Allies were on the offensive.

Early on the morning of 11 November, the 6th Cavalry Brigade left its billets in the Belgian border village of Ramecroix, assembled in Barry, just a mile along the road, and set off east. At ten o’clock, just as Euan was entering the next town, Leuze, the “Cavalry Corps Car arrived with news that HOSTILITIES CEASE 11 AM!”

The streets filled. Every door opened and women stepped, children ran, infants toddled, old men hobbled down onto the cobblestones in a chattering, bubbling, screaming mass. “Great demonstration,” Euan wrote, “in LEUZE square.” The Cavalry left them to it. They moved east of the town “to clear road” and waited. At a quarter to one an “aeroplane message was dropped ordering us back to last night’s areas.” Euan returned to Ramecroix, “where we now have a lovely chateau and celebrated with a big hot bath and gala dinner; finished all the champagne.”

Five days later, on Saturday 16 November, he “got two letters which decided me to go home as soon as possible.” The first was from Stewart, asking Euan to be best man at his wedding to Avie in ten days’ time.

The other was from Idina.

Chapter 11

I

dina had taken a lover. His name was Charles Gordon and she had met him at the flat of a woman called Olga Lynn. Olga Lynn was a professional singer and singing teacher, and Lynn was not her real name. She had changed her surname from Löwenthal on moving to London from Germany.

1

Keen to be invited to the parties at which she was hired to provide the after-dinner entertainment, socially she was a busy bee of a woman, given to emotional outpourings and intense friendships, and was widely “suspected of being a Sapphist.”

2

She lived in a large house in Catherine Street, a Georgian terrace in the shadow of Parliament. She filled it with guests, for drinks, for dinner, for the night. It was a crossroads where art collectors mixed with actors, dancers, and the pleasure-seeking end of high society. There was always some sort of party going on in the evening at Oggie’s, as her friends called her.

When Euan went back to France, Idina found herself going round to Oggie’s. Whenever Idina turned up, the tiny Oggie threw her arms open and let out a whoop of joy. And there, in a haze of cigarette smoke and champagne, Idina met Charles.

Like Euan, Charles Gordon was a Scot who had been sent south to Harrow School. He was four years older than Euan, and their time there had overlapped—Charles was in his last year when Euan was in his first—but the age gap had been too great for them to have been friends. Also like Euan, Charles was pale-skinned, dark-haired, good-looking.

However, for Idina his attraction was very different from Euan’s. Whereas Euan could hardly let a minute slip by without filling it with some social activity, Charles took a distinctly—perhaps overly—relaxed view of life.

3

He and his slightly older brother, Jack, had been orphaned by the time Charles was eight. The rest of their childhood had been spent being shuffled between boarding schools in term time and maiden aunts in the holidays. At the age of twenty-one Charles and Jack had each inherited from their father a share of a house in Aberdeenshire and the money required to keep the house and land going. Unfamiliar with the property, the two young men had felt no attachment whatsoever to it. They therefore started to celebrate their newfound freedom from dormitories and spinsters by spending the money on a life free from labor and care.

Dormitories and spinsters had, however, ill equipped Charles and Jack for the pitted maze of London life. The money ran through their fingers as fast as they extracted it from the bank. Jack, who was the more insular of the two and tended to avoid romantic entanglements, found a steadying hand among the incense and reverberating chants of the Catholic Church. He decided that, if his pot ran out, he would take holy orders and retire to a monastery rather than dampen his brow in the world of wage-bearing work.

4

As a consequence, he battened down the hatches of expenditure and stopped passing over a single penny more than was strictly necessary.

Charles, by contrast, as his daughter later said, found a life of such fiscal and other abstinence less than appealing. His eye automatically followed an attractive woman as she crossed the room.

And, more often than not, the attractive woman, once she had noticed Charles, his dark hair, his height, his strong cheekbones and jaw framing a pair of twinkling, inviting eyes, recrossed the room toward him. With his air of falling back into a comfortable chair, Charles invited approach. He had broad shoulders, a long attention span, and an endless supply of handkerchiefs. If help was needed, he took enormous pleasure in providing it.

5

Idina fell into Charles’s comfortable chair. Here was a man interested in only her. He offered Idina the affection she craved but was no longer receiving from her husband. Instead of glancing over her shoulder for the next invitation he showed no ambition for anything except an easy, pleasant life. Charles showered her with attention and sympathy. With the prospect of her husband returning to her appearing unlikely, Idina

slept with Charles not just once or twice but again and again and again. At first it was covert adultery: endlessly changing rooms and flats. But crossing town at unearthly hours was a tiresome business. They began to go out together, ceasing to care if anyone saw them, or what anyone said. They went down to Brighton, where Idina had spent so many weeks the year before, and moved into the Metropole Hotel. There the two of them could lie side by side and whisper of the life they might have had if Idina were free, if she had met Charles first, if there wasn’t a war on. Charles told her about East Africa—which he had visited—and its gardens of Eden clinging to the slopes of its mountains, limitless fresh, sweet food that came in harvests not once but two, three, four times a year, and wide-open plains where animals ran free, uncaged.

Within a few weeks Charles had filled the space that Euan had left open.

IN OCTOBER IT BECAME CLEAR

that there was not much of the war left. Euan would soon be home. Idina had to consider the prospect of trying to rebuild a life with a man whom she loved but who might any day leave. During her years apart from Euan they had developed lives so separate that it was hard to imagine pulling them back together again. Like Euan, Idina could have simply drifted from lover to lover. But she feared the future, and what old age might bring.

6

Her paramours would cease to visit. Euan, if he hadn’t already left her for another wife, would be out at the latest social occasion or in some mistress’s arms, and with all that money, however advanced his years, he would never be short of either mistresses or would-be wives.

Idina had been scarred by Euan’s semi-disappearance. She felt that there was something very wrong about her husband being targeted by women who wanted not just to be close to him (which she could put up with), but to take him away from her altogether and marry him. However many lovers she would have in the years that followed, it was said of her that “she never stole other women’s husbands, but might pick them up if they were left lying around.”

7

To Idina “left lying around” would show itself to mean either sanctioned by their wives to sleep with whomever they chose, or abandoned by wives adventuring abroad. It would not mean husbands who were at a loose end while their wives were sick.

In the autumn of 1918 Idina was twenty-five. Her life had hardly begun, yet the life she had been planning with her husband appeared over. Twenty-five, however, was young enough to start again and, in the

aftermath of a war that had broken both a continent and a generation, everyone who could was starting over, including several of Idina’s closest friends, among them Dorry Kennard and Rosita Forbes. These women were not retracing their steps to a time before the war in order to relive the same marital disharmony: they were setting off on great adventures and new lives. Marriage to a handsome, rich Cavalry officer had been Idina’s attempt to conform to the social norm of the day. It had also been a rebellion against her unconventional upbringing. Now, both convention and rebellion had failed her. After a fatherless childhood, she had been looking for a man who belonged to her. Euan clearly no longer did. And Idina’s instincts turned her toward the examples of her upbringing. Like her mother, she was not going to take second place in an unhappy marriage. And the blood of her globe-circling grandmother, Annie Brassey, ran deep in her veins. Right now, the lives led by Idina’s girlfriend explorers were more familiar territory to her than a loveless life with Euan. Somewhere there had to be a better life than this one, painfully married to a man she still loved but who no longer seemed to love her, in a country heavy with grief.

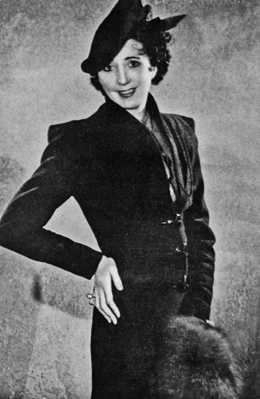

Idina’s friend the travel writer Rosita Forbes

Idina’s confidence, however, had been rocked by the failure of her marriage. She was not going to go abroad alone. She needed someone who loved her to come with her. There was Charles. And East Africa was now offering all former soldiers the chance to buy farms there. A farm would, again, offer Idina a life like the one she had grown up with.

Idina suggested to Charles that they go to Africa.

8

She had ten thousand pounds (the equivalent of a million today), which her mother had given her in her own name on her marriage to Euan. It was enough to

buy a farm and live off of it until, on three harvests a year, they could make it pay. And there they could live the English idyll that this terrible war had fought so hard to destroy. They could spend their early mornings riding and the rest of the day on the farm in brilliant sunshine. It would be a life in paradise where what money they had would go a long way.

On 11 November, the day the Armistice was signed, as the nation celebrated and her sister, Avie, was planning her marriage to Stewart, Idina wrote to Euan asking for a divorce.

On Wednesday, 20 November, Euan reached Charing Cross Station at ten to three in the afternoon, surprised to find nobody there to meet him. “Got a taxi home: Dina had never got my wire,”

9

he wrote, as if unable to understand what asking for a divorce meant.

Idina was waiting for Euan at home. She hadn’t seen him for almost half a year. Yet his face was still the same one that she had spent years wanting to reach out and touch.

Before either of them had a chance to talk, tea arrived. Rapidly burdened with a saucer and a cup full to the brim with scalding liquid in one hand, and a sandwich plate in the other, neither was able to say anything of any meaning whatsoever until after it had all been cleared away.

Then they sat by the window overlooking Hyde Park and its expanse of dulling green autumn grass pockmarked by brown mulch pools of leaves, bare-armed trees reaching above. The light was almost gone. They spoke about their marriage. “Important discussion with D after tea,” Euan wrote. It would be five years the following week: five years, two children, a not yet half-built house several hundred miles away. Not quite a year and a half of that time had been spent on the same side of the Channel, during a war that they thought had been the beginning of the end of the world.

Idina did not want to remain married to a man who had so openly forgotten he had a wife. She didn’t mind what anyone thought, but she wanted a divorce and a chance to start again. Euan would easily find witnesses to win him a divorce from her, if that was how he wished to do it.

The light outside had gone, but when Idina looked up she would have seen that this discussion had come as a relief to Euan: “explains much, thank goodness,” he wrote later of their afternoon’s conversation. His reaction was not surprising, considering that, if Idina had tried to

divorce him by claiming desertion, he would have been thrown out of the Life Guards.