The Bolter (12 page)

Authors: Frances Osborne

He told Idina that he’d be back at twelve-thirty Wallace Cuninghame was coming over then, to go to lunch at Madame Barrachin’s.

And he was gone.

Two days later, on Wednesday, the two of them went first to the permit office, then to the prefecture “to get her Passports done,” wrote Euan. Not that Idina could travel yet. The U-boats were hitting their targets and the boats to England had been stopped. “Harben promised to let her know when they would start.” They lunched “upstairs at 12.” For forty minutes they chattered about everything except the war and when, or if, they might see each other again. And at twenty to one precisely Idina grazed her lips on Euan’s moustache, closed the door behind him, and listened to the sound of his motor taxi rattling across the cobbles of Place Vendôme and away.

But it was not the war that would take him from her.

Chapter 6

T

he next time Idina saw Euan was in London, on 1 June 1917. He arrived more or less straight from a week in the trenches which, this time, hadn’t been as bad: “Nice little dugout: no rats.”

1

And he was only a day late coming home. The relief hadn’t arrived until a quarter to three the morning before, and by the time he had reached HQ there were no cars left to take him to the station that day. So he had come on Friday, in the General’s car and via GHQ. He caught the 7 p.m. boat from Boulogne and reached Victoria at 11 p.m. “Dina had got my wire from Folkestone and was there to meet me.”

London at night was quiet. The streets were dark, windows blacked out and lamps extinguished or covered in dark-blue paint. The traffic, which had thinned by day, was, by the evening, barely evident. A week earlier the first bomb-bearing airplanes had reached the Kent coast and opened their carriages, killing just short of one hundred. London—today, tomorrow, in a week or two’s time—would be next.

The few who ventured out in the blackness scuttled between darkened doors. Barely a household remained untouched; many held an empty bed or chair of somebody who was no longer there. Those who were at home, khaki cuffs scratching their wrists, white knuckles clenching rolled-up cigarettes, felt their names churning in the great lottery of death across the Channel. Which would it be: slowly, “from wounds,” in a French field hospital; mustard gas—the worst, especially

if it didn’t take a man at once; or the swift, merciful obliteration of a direct shell that would leave not a shred of skin at all?

Yet life went on. One hundred feet underground, Tube trains rumbled through the city’s veins. Behind the scarred front doors and blinds, lights flashed on and off, babies were born, old folk died, and young couples married, quickly, desperately, before they said good-bye. Restaurants, limited to two courses at lunch, three at dinner, and no meat on Tuesdays, were still open until their 10 p.m. curfew. And they were full.

Any man home on leave deserved to enjoy himself. Great groups of friends gathered in the best place they could afford. The women fluttered around, at lunch, at tea, then dressed for the evening, in elegant, subdued hues and long, dark lines that dropped from below their busts to a few inches above the floor. They ate early and went to one of the dozens of lighthearted musicals in town:

Bing Boys, Bing Girls, Bubbly, Topsy Turvy, The Maid of the Mountains

, or

A Daughter of the Gods

. But even these were curfewed, and at half past ten they were out on the streets again, hunting for the hidden entrance to one of Soho’s hundred-odd illegal nightclubs where they could sip whisky from coffee cups until dawn.

The young drank anything, and anywhere they could. When the government imposed curfews on the serving of alcohol, and the nightclubs had opened, patrols were sent around the streets to stop drunken behavior and heavy petting in public. Where they could, friends piled into houses for “bottle parties,”

2

even to inject morphine together—and to spend the night. Fearful of not seeing each other again, some couples seized what might be their only chance to share a bed. The new duty to show a man who was about to die a good time began to override the old mores of virginity until marriage. Especially as marriage itself became an ever-retreating possibility. There were fewer and fewer men left to marry. Girls began to call themselves by boys’ names as nicknames: Euan’s diary reverberates with Jonathan and Charles in quotation marks. Any man who came back from France in more or less one piece found himself surrounded by a gaggle of girls. Even the married women became more predatory in a near-frantic need to prove themselves still able to attract a new man, should their own not return. Any man, single or married, was fair game.

Some nights there were dances in private houses. One of the great hosts of the day, the writer George Moore, strewed white lilies over dozens of tables, hired two bands, and kept his guests dancing until

dawn. He opened his doors almost as often as it was still decent. Each time, some guests would go back to France and never return. The evenings became known as the Dances of Death.

Idina, glowing, at the front of the crowd on the station platform, watched Euan walk toward her. His cap was straight, shoulders still square, feet stepping briskly forward. Idina had a glorious twelve days with her Brownie

3

ahead of her: almost two whole weeks of strange wartime married life, in which Euan’s duty was to have as good a time as he could and Idina’s was to keep him entertained with a frenzy of social and sexual activity.

They rattled back through the empty streets to Connaught Place and ran upstairs.

Euan’s diary records how the next day the social activity began: on Saturday it was just a lunch party, an afternoon walk in the park with friends, dinner at the Carlton, and the hit show of the year,

The Maid of the Mountains

, “where we occupied the enormous stage box!” On Sunday they set out “in the Rolls,” picked up two friends, and drove west out of London and into a barely recognizable countryside. Every inch of rolling green field and sloping lawn had been plowed brown and planted with corn now turning gold. Baggy-trousered Land Army girls wearing knotted headscarves and with rolled-up sleeves were bent double at work.

Outside Slough they burst a tire and “had some trouble putting on the new wheel!” Half an hour later they reached Maidenhead Boat Club for lunch, where they then went on “the river in an electric launch until 7 pm. Took tea with us.”

For a wartime afternoon, it was idyllic. Idina had succeeded in her task of entertaining Euan: “Dined at the Club (Lags joined us for dinner) and had a ripping run back after: car going beautifully.” It must have appeared the perfect start to a perfect fortnight.

But, on Monday morning, after barely more than a scrabbled-together twelve months of married life in the same country, the trouble began.

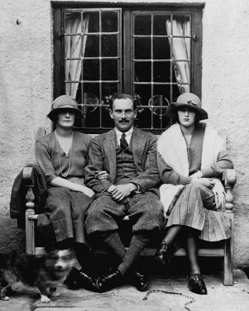

It began with Idina’s sister, Avie. Avie came to lunch at Connaught Place. Now nineteen, she was tiny like Idina but heavier-boned. Her shoulders were square, her cheekbones, nose, and jaw heavier. She was not, as the press rather unkindly pointed out, as attractive as her elder sister. However, the friend she brought with her was beautiful: given her ambition and the extent to which Euan enjoyed her company, disturbingly so.

Barbie Lutyens was eighteen years old and the eldest child of the most renowned architect in Britain, Edwin Lutyens. Lutyens had designed dozens of “modern” country houses in Britain and public buildings all over the British Empire. He was now working on the new Viceroy’s Palace in Delhi, a monumental building with several miles of passageways. Like Idina and Avie’s mother, Muriel, Barbie’s mother, Emily Lutyens, was an ardent Theosophist. When Krishnamurti had come to England in 1911 he had left Idina and Avie’s house to spend his summer holiday with Barbie’s family. There was also another connection between the two families.

Emily Lutyens had formally broken off sexual relations with her husband. And over the past year Edwin Lutyens had become close friends with one of Idina and Avie’s Sackville cousins: Victoria, Lady Sackville. Unlike the Sackvilles, however, the Lutyens family was, comparatively, frustratingly poor, and Barbie’s family and her parents’ relationship were constantly beset by money worries.

Barbie was tall and slender with endless legs, ice-blue eyes, and dark hair. Her skin was porcelain, her jaw sculpted. Her mouth was wide, childlike, giving her the air of a doe in some woodland glade. But this aura of treat-me-like-a-Ming-vase concealed a determination of steel. Barbie was embarrassed by her mother’s Theosophy and social reticence and by her father’s endless jokes.

She was irritated at the way in which the family lurched from financial crisis to crisis, moving into ever-smaller homes. She wanted a rich husband and a glamorous social life. As her sister, Mary, wrote in her biography of their father, Barbie “was determined to get out of her milieu” and had an “ambition of being accepted in smart society”

4

After leaving the coeducational King Alfred School in Hampstead the year before, Barbie had gone to Miss Wolff’s, a smart finishing school in South Audley Street, Mayfair. Upon leaving she had joined the middle- and upper-class nursing service of the Voluntary Aid Detachment and trained at a hospital near Aldershot. The moment her training was complete she had moved to Mayfair, where her aunt, the Countess of Lytton, had started a nursing home for officers in Dartmouth House, a mansion in Charles Street. Barbie had found Avie working there. The two of them had become firm, inseparable friends: Avie bitterly aware of being less attractive than her sister, and Barbie bitterly aware of being less wealthy than her friends. For Idina, this was to prove a fateful combination.

Two tennis-packed days later, Barbie reappeared. She accompanied

Avie to tea at Connaught Place. Tea—the great British at-home social moment of the day—continued unabated, almost as an act of wartime defiance. Flour was gray, butter, sugar, and eggs scarce. Nonetheless, ashen sandwiches, scones, and transparent jam were arranged around the gently diminishing stacks of an empty cake platter, carried in by uniformed servants also bearing engraved trays laden with silver teapots and delicate porcelain cups and saucers.

Barbie, with her swan neck and big eyes, folded herself into a chair for an hour or so. It was not a long visit, but it was long enough: Euan was clearly hooked.

He had to spend the next day, Thursday, at his barracks in Windsor, and Idina went with him to keep him company. But back in London on Friday morning, Euan dashed out by himself first thing. He took Idina’s small Singer car and “visited Avie and Barbie at their hospital.”

Slowly, a gap seemed to open up between Idina and her Brownie.

In Paris they had been living together in a hotel room, with nobody but each other to talk to, every moment of their day in tandem. In London, however, they were in a house spread over seven floors and twenty rooms, with children to see—although in his diary Euan mentions only David and only once—and a stream of servants and daily business. This time he didn’t give Idina his diary to write in. He had reason not to: Barbie appears on every single page for the rest of his leave.

That Friday evening Euan and Idina had fourteen for dinner and fifty to dance. “A great success,” wrote the ever socially aware Euan, “cutting out three other dances which were taking place the same night.” Barbie took herself home at dawn but, the following afternoon, when he and Idina drove down to Wimbledon to play tennis they “found Avie and Barbie there.”

And so it went on. On Sunday Barbie arrived shortly after breakfast for a lift to the Maidenhead Boat Club, where she slipped herself into Euan and Idina’s punt. When the boats stopped for tea, Idina succeeded in swapping Barbie for one of her own girlfriends. But the next day, Euan’s last in London, Barbie came back to tea at Connaught Place with Avie, and Euan asked both girls to say good-bye to him over lunch the next day. They came. By the time they went back to their nursing home, Idina had less than an hour with him left.

But Idina had not yet lost Euan. When he returned to France he continued to write at length, if marginally less frequently than before. And, ten weeks and several dozen scribbled letters later, he was given some

Paris leave. On Friday, 24 August, Idina crossed the Channel to meet him. After the near-constant presence of her younger sister’s eager single female friends in London, Paris offered Idina a chance to spend some time alone with her husband.

However, when Idina reached the Ritz she discovered that she and Euan would not be alone after all. Instead of a flock of single girls, wings flapping, beaks at the ready, she found Stewart Menzies—Euan’s almost ever-present and too adoring friend. Stewart and Euan were bonded by the Life Guards and their Scots blood. Away from each other for too long, one would twitch, make his way to the nearest telephone, and track the other down. Stewart could be found through GHQ. And GHQ could always find Euan for Stewart. If Euan needed a hard-to-find car ride, a pass, a place for the night, he called Stewart. And Stewart provided. Now, having not seen Euan for several weeks, Stewart had come to Paris to meet him.