The Bolter (4 page)

Authors: Frances Osborne

Muriel’s own parents, Thomas Junior and Annie, had also pushed the boundaries of the world in which they lived. Annie was plagued by chest infections throughout England’s damp winters. Rather than spend the winter months lingering in a deck chair in a hotel in the South of France, she decided to turn this handicap to her advantage and travel more

adventurously. By the time that Thomas Senior died and bequeathed Idina’s grandparents a share of his substantial fortune, Annie had already traveled extensively in the Near East. She recorded her adventures with the recently invented photographic camera. Now in possession of near limitless funds, she commissioned the building of one of the world’s largest private steam yachts, the

Sunbeam

. The specifications included a library of no less than four thousand books and a schoolroom. Breaking with Victorian traditions of keeping children out of sight, her four surviving children moved on board; the youngest was barely a year old. Annie had long suffered from debilitating seasickness, but she was determined to ignore it, and started on a voyage that would make her the first person to circumnavigate the globe by steam yacht. The

Sunbeam

was 157 feet in length and had both captain and commander, a resident doctor, and even an artist—as well as a crew of thirty-three. The journey that Idina’s grandparents embarked upon took eleven months. The

Sunbeam

set sail from Southampton, England, on 1 July 1876 and traveled west across the Atlantic to Rio de Janeiro, which it reached by mid-August. Thomas Junior and his son, also Thomas, then returned to England. The son went back to school at Eton, the father went back to Parliament, to which Annie had dispatched him to promote the cause of female suffrage. Over the next nine months, Annie and her three daughters, Muriel, Mabelle, and Marie, visited, among other countries, Brazil

and Chile. They rounded the Strait of Magellan at the tip of South America, spent Christmas and New Year’s in Hawaii, a further month in Japan, weeks in China and Sri Lanka—all interspersed with months at sea—before slipping up the Suez Canal and through the Mediterranean and back to the British holiday resort of Hastings. The five-year-old Muriel and her siblings had thus spent formative days quite literally being washed overboard and rescued as they collected botanical specimens in the South Seas, and their evenings climbing volcanoes to feast with local chieftains and, in between, learning to scrub the decks. Annie kept a detailed diary of these adventures, which she published under the title

A Voyage in the “Sunbeam,”

The book was a success—partly, perhaps, because the trip had not been without incident. The

Sunbeam

caught fire three times, including one long, terrifying blaze that lasted all night, recounted in detail by Annie. In the Magellan Strait, she and the girls had come across a cargo ship carrying coal that had started to burn. Almost as soon as the fifteen-man crew had been hauled up onto the

Sunbeam

their vessel burst into flames.

A Voyage in the “Sunbeam”

was also packed full of the domestic detail of traveling for so long with a young family on board. The book was reprinted and published in several editions in the United States and Canada and was translated into several languages.

2

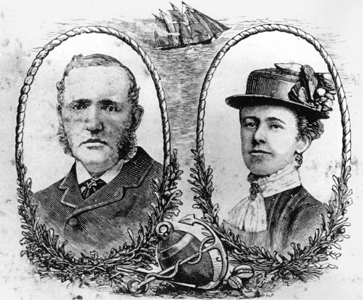

Idina’s grandparents Annie and Tom Brassey Jr

.

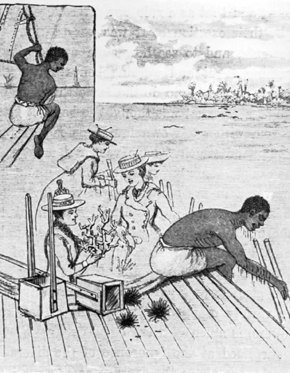

Annie and children pulling specimens out of the South Seas

Idina’s mother and aunts were catapulted into worldwide celebrity, accustoming them to living in the glare of publicity. In Muriel’s case, this appeared to have a lasting effect. Seven years old when

A Voyage in the “Sunbeam”

was published, she was almost too young to remember any other way of living. When in adult life she was faced with decisions that

most of her contemporaries would have shied away from for fear of drawing unwelcome attention from the newspapers, Muriel barely blinked and steamed ahead.

Annie went on to travel for a further decade. In 1887 she died of malaria, off the coast of Mauritius. However, even from beyond the grave, she appeared to live on. A quarter of a century after it was first published,

A Voyage in the “Sunbeam”

was used as a school textbook—and it is still in print today.

3

Annie’s husband, Thomas, went on with the crusade she had set him: using his parliamentary position to argue for votes for women.

Thomas Brassey was a member of the British Liberal party, known as the Whigs, whose leader was the morally austere William Gladstone. Gladstone is regarded alongside Winston Churchill as one of Britain’s greatest prime ministers—an office that he held four times. However, he is also known for his curious private life, in which he practiced self-flagellation and invited prostitutes into his home, as he explained, to talk them out of their profession. Gladstone believed in the extension of suffrage, but only to a wider group of men, not to women. Thomas Brassey sought to persuade Gladstone otherwise.

To that purpose he entertained Gladstone and his entire Cabinet at Normanhurst Court, his sprawling mock-French château in Sussex, and at his double-width house in Park Lane. At the back of the latter he had put up a two-story Indian palace, known as the Durbar Hall, bought from a colonial exhibition in London. He used it to display the trophies Annie had collected from her travels and, after her death, proudly opened it to the public twice a week. And, by the time Muriel married Gilbert, her father, Thomas Brassey, son of a railway builder, Member of Parliament, had become Sir Thomas, then Lord Brassey, and was on his way to being an earl himself.

But he still wasn’t grand enough for Gilbert’s parents. Eight hundred years on, the Sackvilles remained ardent courtiers. Their darling son had, after all, been a childhood playmate of the next king but one

4

and should not be marrying into a nonaristocratic family who had been obliged to make their money in Trade. Even more upsetting for them was that this Trade and the newness of the Brassey money were so obviously displayed. For a start there was all the soot and dirt and steam of the railways. And then there was Normanhurst Court, with all its bright-red brick, ornate ironwork, gratuitous church spire, general Francophilia, and even its name, reeking of ill-judged effort. And it was right on the De La Warrs’ doorstep in Sussex: the two families vied constantly over

who should be Mayor of Bexhill. The old Earl and Countess De La Warr refused to attend their son’s wedding.

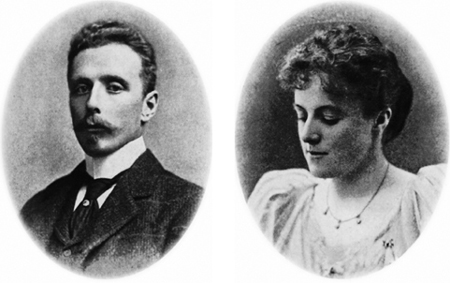

Idina’s father, Gilbert Sackville, and her mother, Muriel (née Brassey)

Thus disapproved of, Idina’s parents had careered through their marriage at speed. Idina arrived within a year. She was named after the wife of Muriel’s brother, Tom, but was fashionably given a first name, Myra, by which she would never be called. By the time Idina was three, Muriel, like her own mother, was herself pushing the boundaries of traditional society by opening Britain’s first mixed-sex sea-bathing area at Bexhill; hitherto men and women had been separated not just by balloonesque bathing dresses and machines, but beaches too. And, together with her husband, she had started racing the brand-new motorcars along the seafront. That same year, Gilbert’s father, perhaps reeling from the shock of all these modern goings-on, died. Gilbert therefore inherited the title of Earl De La Warr and Muriel became a countess.

The following year, Muriel’s second child, Avie, was born and her husband left. Three years after that, in 1900, Muriel surprisingly gave birth to her husband’s son and heir, Herbrand, called Buck as a shortening of his earl-in-waiting title of Lord Buckhurst. She then, as if to prove her parents-in-law’s prejudices right, launched what was seen as an attack upon the upper-class establishment by divorcing Gilbert.

For Muriel, divorce promised both practical and political progress. Practical because divorce would prevent Gilbert from spending any

more of her money on other women. Political in that it would show that a woman need not be tied to an unsatisfactory husband.

For Idina, however, her parents’ divorce would be less beneficial. It set the example that an unsatisfactory husband could be divorced and introduced her to the idea that husbands and parents can leave. Both patterns of behavior Idina herself would repeat, while reaching out for constant physical reassurance that she herself would not be left alone.

For a young child of divorced parents in Edwardian England, life was not easy. The divorce immediately set Idina and her siblings well apart from their peers, for it was, in 1901, extremely rare—even though, among a significant tranche of the Edwardian upper classes, adultery was rife. Along with hunting, shooting, fishing, and charitable works, adultery was one of the ways in which those who did not have to work for a living could fill their afternoons. The term “adultery” is chosen carefully, for it applies only to women who were married. And it was married, rather than unmarried, women who were likely to pass the couple of hours between five and seven (known as a

cinq à sept)

in the pattern set by Queen Victoria’s pleasure-loving son, King Edward VII, and his coterie of friends. This group had been named the Marlborough House Set after the mansion Edward had entertained in as the Prince of Wales before becoming king.

The choice of this hour of the day was purely practical. It took some considerable time for a lady to unbutton and unlace her layers of corsets, chemises, and underskirts, let alone button and lace them up again. Lovers therefore visited just after tea, when ladies were undressing in order to exchange their afternoon clothes for their evening ones.

Where the King went, society tended to follow. If he took mistresses among his friends’ wives, then so could and would those of his minions with both the time and the inclination (although many remained appalled by his behavior). Married women were safer. First, they were not going to trap a man into marriage. Second, if they became pregnant, the child could be incorporated within their existing family. For this reason a married woman was expected to wait until she had produced two sons for her husband (“an heir and a spare”) before risking introducing somebody else’s gene pool among those who might inherit his property—thus “adulterating” the bloodline.

As long as a high-society married woman followed these rules of property protection and kept absolute discretion, she could do what she liked. In the oft-cited words of the actress Mrs. Patrick Campbell, “it doesn’t matter what you do in the bedroom as long as you don’t do it in

the street and frighten the horses.” The boundary between respectability and shame was not how a woman behaved, but whether she was discovered. If she was, her husband could exercise his right to a divorce: for a man to divorce his wife, she had to be proved to have committed adultery.

A woman who wanted a divorce, however, not only had to be wealthy enough to support herself afterward but also needed to prove one of a handful of extreme grounds. A man’s infidelity counted for nothing, since any illegitimate children he produced would stay outside both the marriage and inheritance rights. A woman who wanted to escape an unhappy marriage had therefore to choose between two equally difficult options. The first was to prove not only that her husband had committed adultery but that the adultery was incestuous or that he had committed bigamy, rape, sodomy, bestiality, or cruelty, or had deserted her for two years or more. Or she had to be branded an adulteress herself.